By Rachael Isom, Assistant Professor of English, Arkansas State University

In recent years, many published authors have taken to Twitter to promote their work and engage with readers. We might think about popular writers like Celeste Ng or Lin-Manuel Miranda, both of whom maintain active online presences and tweet about everything from book signings to traffic jams. Social media has given us more immediate access to the thoughts of people who write them down for a living, but these kinds of author-reader exchanges aren’t new. Authors were concerned about how to present their work publicly and respond to criticism long before the Internet made it so easy. As I observed during my recent residence as a Visiting Scholar at the Armstrong Browning Library (ABL), many 19th-century writers took care to construct literary personae, to monitor how those public selves were received, and sometimes even to respond.

My current project analyzes how “enthusiasm”—a term that, in the 18th century, signified both religious zeal and poetic fervor—captured the interest of British women writers in the early 19th century. Enthusiasm was an important concept for describing personal experience but also for presenting a public self. I’m interested in how women used the figure of the female enthusiast to engage with a Romantic poetic theory that had made it difficult for them to respectably claim inspired genius and powerful emotion. At the ABL, I took both broad and targeted approaches to this question. I explored the 19th-Century Women Poets collection to see how women were writing about enthusiasm in the 1820s and 1830s; then I consulted the ABL’s materials to better understand how this legacy influenced Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s self-presentation and response to critique. This post analyzes one such moment of exchange in EBB’s early career.

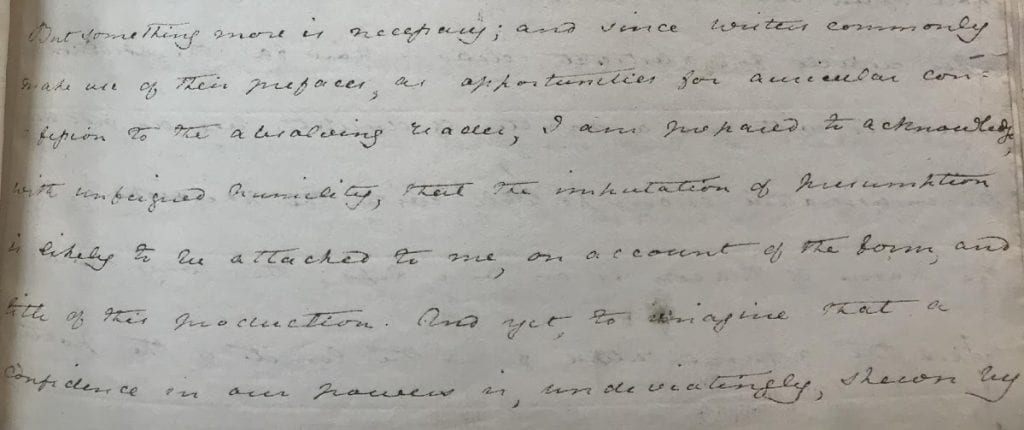

In 1826, EBB published anonymously An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems, and the event came with high expectations from the poet and her parents. The title poem—the fair copy of which resides at the ABL—is a philosophical essay in blank verse. The preface anticipates its reception: “the imputation of presumption is likely to be attached to me, on account of the form and title of this production” (iv). EBB heads off critique here but also implies that readers will find a way to “attach” undesirable qualities to her even with no name on the title page. She was already thinking about how this poem would affect her career once her authorship was discovered.

So was Mary Moulton-Barrett. Keen to collect reviews of her daughter’s poetry, she wrote to EBB on April 4, 1826: “Take care of Miss P’s note because I want to preserve all opinions I can collect of the poem (BC, I, 242). The “care” taken by Mary—and enjoined on EBB—demonstrates the family’s desire to establish a thorough record of public opinion.

EBB took her mother’s advice to document the reception of her poems. As she told Hugh Stuart Boyd in March 1827: “[N]o one can be more solicitous to obtain, or more earnest in valuing, fair & candid criticism” (BC, II, 36). Here, I’ll showcase two such critiques of An Essay on Mind. The first consists of marginalia by Arabella Graham-Clarke, EBB’s maternal aunt; the other includes commentary from the Reverend Henry Cotes (1759?-1835), who received a detailed response from a young poet eager to defend her work and hone her craft.

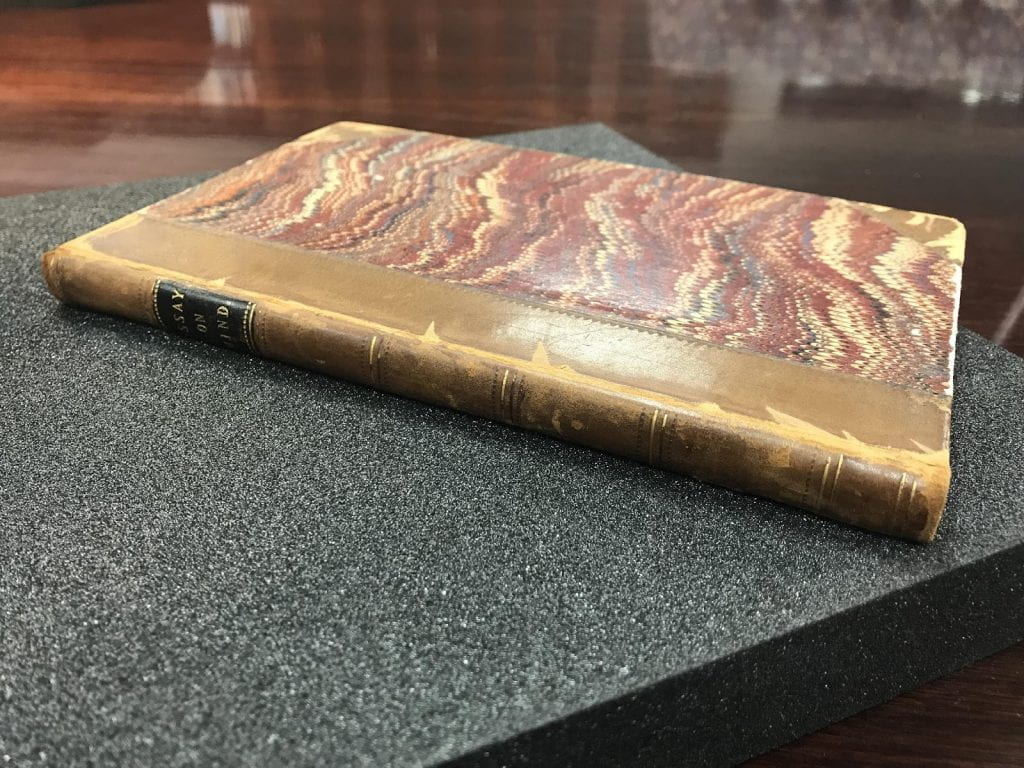

The ABL holds seven first-edition copies of An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems. Copy 6 is a particularly interesting one, as the only name on the title page is that of the owner, not the author.

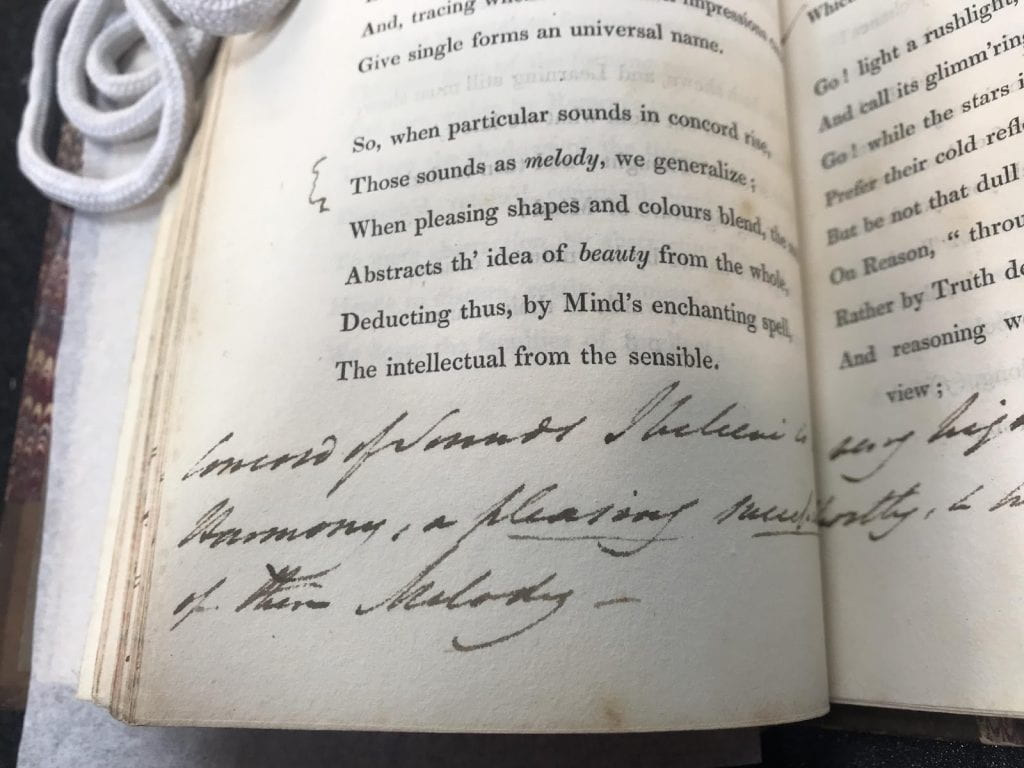

We can imagine Arabella Graham-Clarke receiving this volume and proudly placing it alongside her copy of EBB’s first published work, The Battle of Marathon (also at the ABL). But Graham-Clarke didn’t just collect her niece’s poems—she annotated them. Take, for example, her quibble with the musical metaphor on page 58:

“Concord of Sounds I believe is called Harmony, a pleasing succession of them is Melody –”

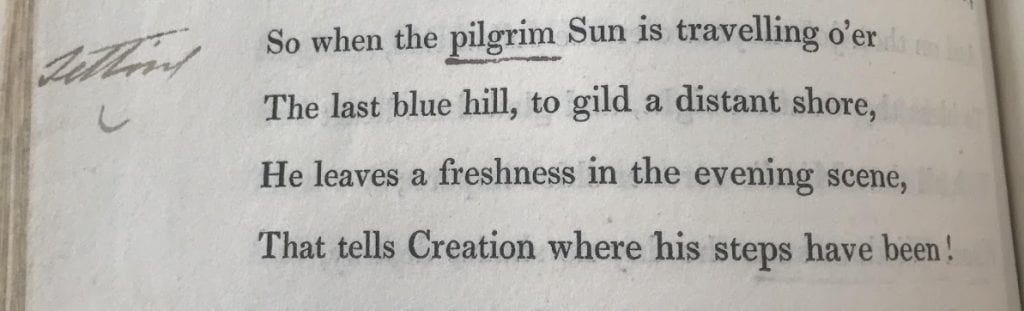

Or her suggestion that EBB substitute “setting” for “pilgrim” on page 88:

These annotations register thoughts many of us have when reading poetry. We ask why a poet uses one metaphor instead of another; we mentally rewrite a particular line. But one aspect of Graham-Clarke’s marginalia surprised me: her astute commentary on form. A good example of this occurs on pages 22-23, where she notes many “bad dactyls, & very few good” in EBB’s poem (22). A dactyl is made of one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables—not an easy metrical foot to use in English—but EBB’s aunt pulls no punches in her critique:

EBB, An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems (1826), Copy 6, pp. 22-23, with “illustrate” underlined on p. 22 and marked with metrical notations on p. 23

This pair works like a footnote. EBB’s aunt underlines the faulty phrase and then explains her objection to it in the lower margin: “I was sorry to see in a Poem of so original a cast & one that gives so great a promise, such a dactyl as ill as that made” (23). It’s a backhanded compliment followed by an in-depth explanation of EBB’s mistake. We might expect this sort of commentary from Sir Uvedale Price, a respected classical scholar who noted the same “bad dactyl” in a letter of July 1826 (BC, I, 252; scan HERE), but its presence in this marginalia is significant because it shows Graham-Clarke’s technical expertise and knowledge of literary history.

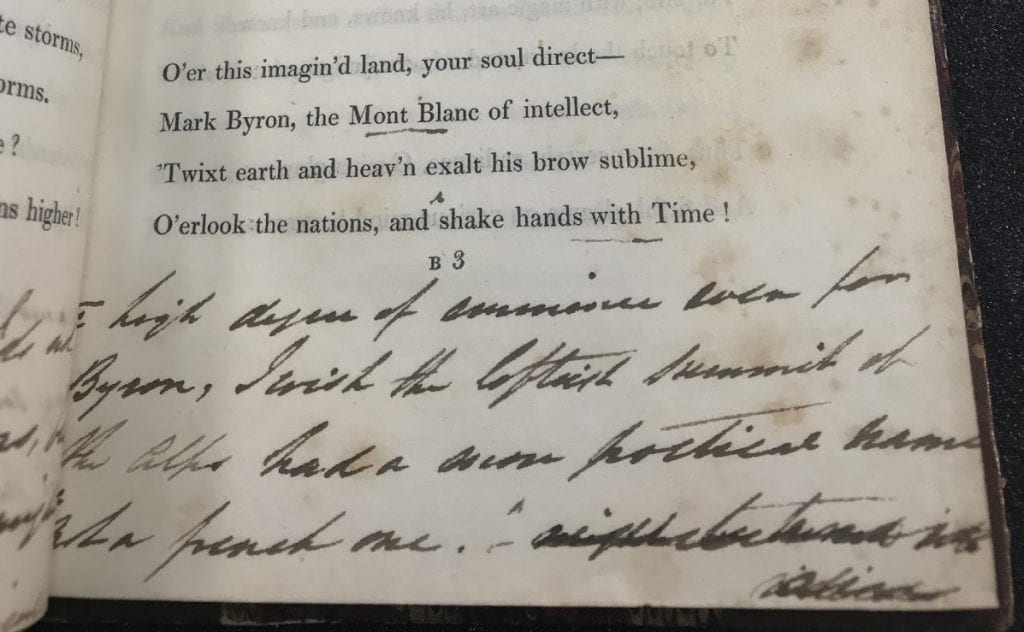

My favorite instance of her marginalia isn’t technical at all. On page 9, pictured here, EBB calls the Romantic poet Lord Byron “the Mont Blanc of Intellect.” Her aunt underlines the metaphor.

“A high degree of eminence even for Byron,” she writes, simultaneously acknowledging Byron’s fame and questioning whether he deserves so much of it. After that, she pivots abruptly: “I wish the loftiest summit of the Alps had a more poetical name & not a French one.” Graham-Clarke’s thoroughly British disdain of anything French takes a literary turn: she wishes that the mountain featured in many Romantic-era poems could be free of its French name. The comment is light, humorous, but also fascinating in terms of political and literary histories. If EBB read these notes, I like to imagine that this particular page made her chuckle as it did me.

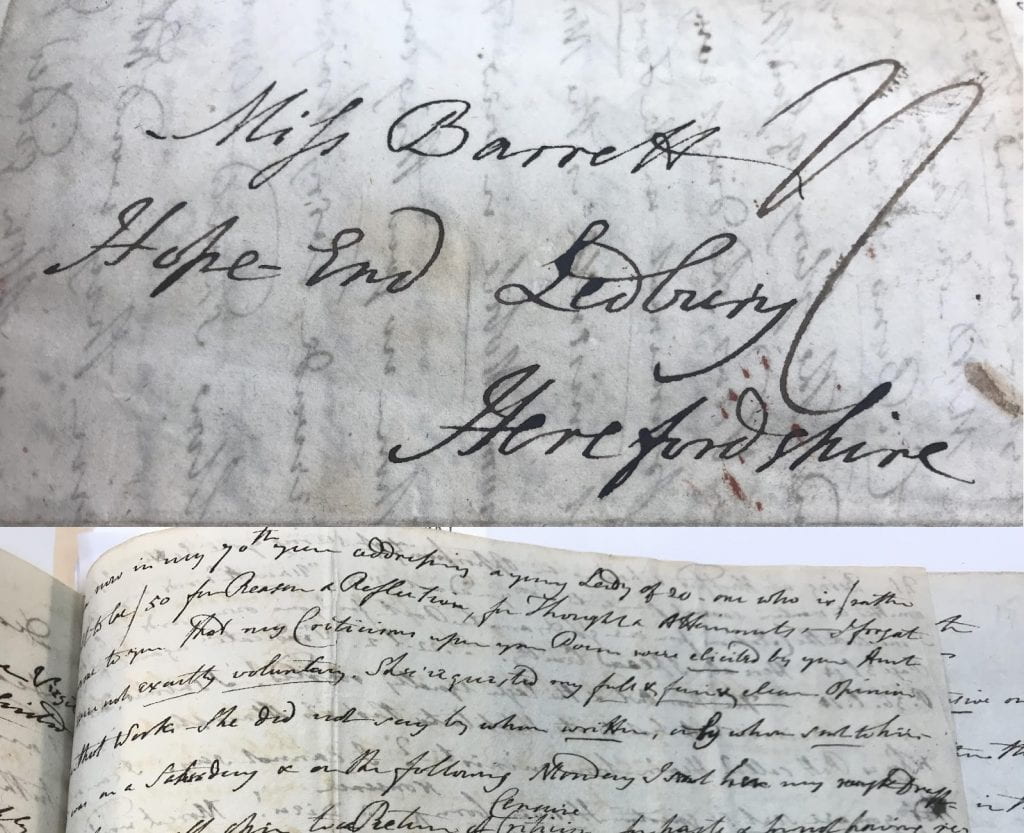

In addition to sharing her own criticism of EBB’s volume, Graham-Clarke appears to have been instrumental in securing a second reader in Henry Cotes, Vicar of Bedlington and a published author himself (see BC, II, 112n). As Cotes explains to EBB later, on March 17, “my Criticisms upon your Poem were elicited by your Aunt they were not exactly voluntary. She requested my full & firm & clear Opinion upon that Work – She did not say by whom written” (Ms. D0250; see also BC, II, 391-92).

From this comment, we learn that Cotes, like many of EBB’s early readers, approached Essay with no knowledge of its author and no expectation of a response. He was clearly surprised to receive what is now Ms. D0250, a spirited letter from the 22-year-old poet, on March 8, 1828:

“I received yr criticisms from Mrs. Hedly who was unwilling that I shd lose such an opportunity of being interested & instructed . . . . I sincerely thank you for a good opinion rendered so valuable to me by the openness & unreserve with which you have mentioned what you departed from & condemned. May I venture to speak to you with great freedom – and to explain exactly exactly [sic], when I at once submit to ‘kiss to rod’ and where I shd. like to escape doing so.” (BC, II, 112; scan HERE)

Along with this autograph letter, the ABL holds Cotes’s notes (which appear in a large hand on small sheets of paper) and return correspondence. Essentially, we have the full picture of this moment in EBB’s reception history, which I’ll present briefly by returning to a couple of the passages mentioned above and showing how EBB contended with Cotes’s feedback.

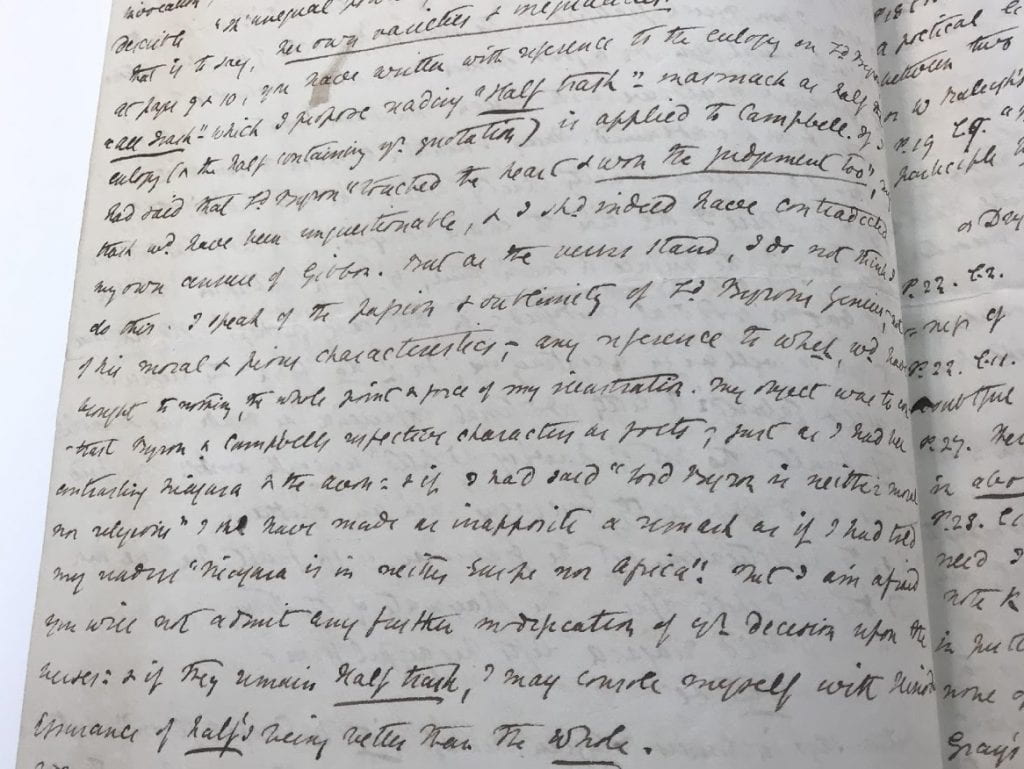

Cotes, too, observes EBB’s praise of Byron, but he harshly calls it “All Trash.” EBB responds: “At page 9 & 10, you have written with reference to the eulogy on Ld. Byron, “all trash” which I propose reading “half trash” inasmuch as half the eulogy (or the half containing yr. quotation) is applied to Campbell. If I had said that Ld. Byron ‘touched the heart and won the judgement too’, my trash wd. have been unquestionable . . . But as the verses stand, I do not think I do this.”EBB’s defense is light yet firm—she is willing to admit flaws in her poem, but she also points out that Cotes’s primary objection comes from his misreading, not her poor writing. I suspect that EBB is also deflecting a rebuke that had become tiresome to her. As a Byron devotee in her youth, she would have contended often with those who viewed her admiration as inappropriate, even sinful. Thus, she qualifies: “I speak of the passion & sublimity of Ld. Byron’s genius, not of his moral & pious characteristics.” Though she imagines Cotes “will not admit any further modification of [his] decision,” she finishes the exchange with a playful flourish: “if they remain half trash, I may console myself with kinder assurance of half’s being better than the whole.”

This isn’t the only place where EBB is willing to meet Cotes halfway. For example, in the case of that deplorable dactyl, “illustrate,” EBB responds to Cotes almost as an editor. She considers his suggestion of “verify” but, finding it unsatisfactory, chooses a third option: “vindicate”:

![Henry Cotes, Comments of EBB’s An Essay on Mind, [Early March 1828] (L0080.1) and Elizabeth Barrett to Henry Cotes, March 8, 1828 (D0250)](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2019/07/image1516_final-1024x842.jpg)

Top: Henry Cotes, Comments of EBB’s An Essay on Mind, [Early March 1828]; bottom: Elizabeth Barrett to Henry Cotes, March 8, 1828 (D0250)

By way of conclusion, I want to express my gratitude to the Armstrong Browning Library for supporting my research on 19th-century women’s poetry. I’m especially grateful to the ABL’s staff for the kind hospitality and invaluable expertise they shared during my stay, and to my fellow Visiting Scholars for the many stimulating conversations we enjoyed in the halls of the ABL. As I’ve tried to show in this post, these are the kinds of exchanges that make scholarship interesting, productive, and incredibly fun.

![Henry Cotes, Comments of EBB’s An Essay on Mind, [Early March 1828] (D0250))](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2019/07/image13_final-1024x345.jpg)