By Laura McNeal

On a dry November day in 1967, she inserted a piece of paper, rolled the paper up, and typed Robert Browning Museum, Waco, Texas.

Gentlemen

She wrote. Then she hit the space bar. Added a semi-colon.

Gentlemen ;

I have never been to Waco.

Waco is three and a half hours from Rio Concho Manor, the nursing home in San Angelo, Texas where she was living. She explained in her letter that she had inherited two chairs that had once belonged to the Brownings. Her grandchildren weren’t interested in antiques or in the Brownings, either, so “if anyone wants them we shall be glad to deliver them.” She enclosed a self-addressed stamped envelope. She signed herself sincerely Florence D. Tweedy.

Fifty years earlier, she’d married and moved to Ecuador with her husband, who’d been hired to manage a gold mine. A daughter was born near the Amazon and was followed the next year by a boy born in New York, followed by another boy near the Amazon. When the girl was old enough, they sent her to boarding school in New Jersey and then to Vassar. The Tweedys came back to live in Texas because Florence’s husband was an heir to the Knickerbocker Ranch near San Angelo.

Two days after she sent her letter, a reply came from Jack W. Herring, Director of the Armstrong Browning Library. He wanted to know every detail about the relationship between the Tweedys and the Brownings, the history of the chairs, and whether Florence had any other relics, especially handwritten manuscripts or letters. Letters by the poets and their circle were still being found, sold, donated, transcribed, and added to lists. New ones would add vital information for researchers and biographers.

On November 22nd, Florence wrote that she was very grateful for the prompt reply. She did have one letter that had not been destroyed, one that somebody had been interested in for an archive. Whether she’d handed over the letter to that person, she didn’t say. She wasn’t driving any more, but her friends or granddaughters would run her over to Waco someday.

Evidently, that was hard to arrange. Four months later, on the last Tuesday in February, Florence boarded a bus. Dr. Herring had asked her to label the chairs with their provenance, so she took two of her calling cards, which said Mrs. A Mellick Tweedy, and on one she wrote “This chair belongs to the Robert Brownings & was given to the Edmund Tweedys when they left for Newport, Rhode Island.” and on the other, “These chairs come from the house in Italy where Edmund Tweedy lived with the Robert Brownings.”

The Edmund Tweedys—her husband’s people–died long ago: Mary in 1891, Edmund in 1901. The Tweedy family still had the birth certificates of a girl born in France and a boy born in the Baths of Lucca, Italy.

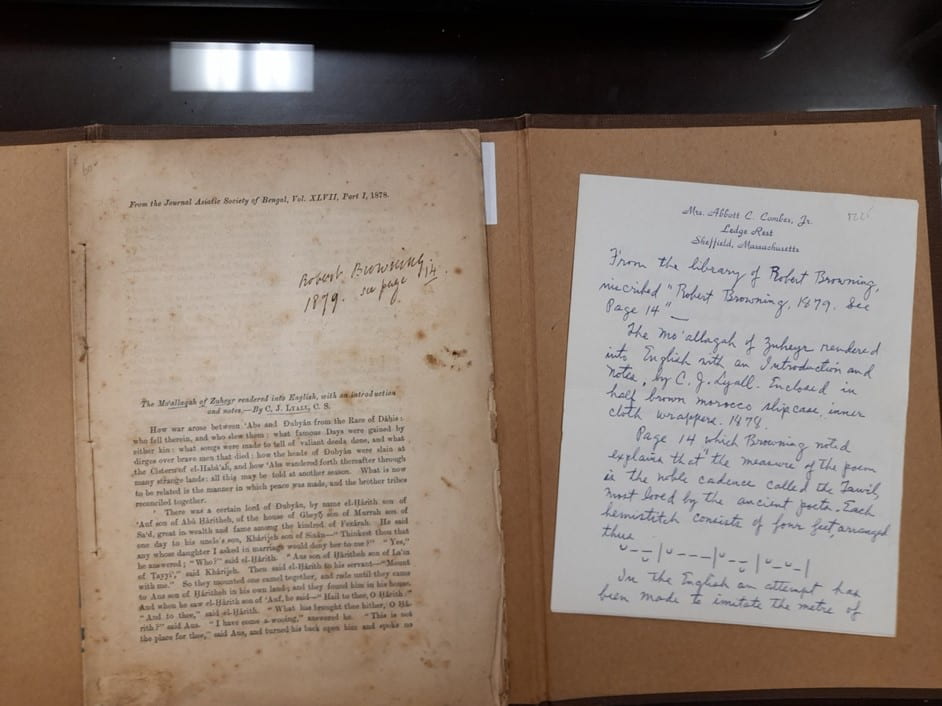

There is no evidence that the Tweedys lived in the same house as the Brownings, as Florence wrote, but they do seem to have lived nearby. We know this because the ABL owns a tiny sepia envelope addressed to

Mrs Tweedy

and amended, in a different hand:

(To the kind care of Mrs Shaw, / Villino Lustrini.)

The part that says “Mrs. Tweedy” matches Elizabeth’s handwriting; the amendment matches Robert’s. The date on the back of the envelope: Nov. 14th 1853 looks like Elizabeth’s writing. There’s no stamp or postmark. A tiny red button of wax has been hardening on the paper for over a hundred years. Inside the envelope, the letter—just a note, really–says:

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Mary Tweedy, [14 November 1853], Armstrong Browning Library, Baylor University, Waco, Texas

My dear Mrs. Tweedy,

I feel as if we were belying our feelings to you in going away as we are about to do tomorrow morning at nine, without even leaving a card at your door, to show that we thought of you in going. I have been hoping everyday to be able to get out for this purpose, & everyday it has proved too cold for my husband to let me take a step unnecessarily into the air– He, half in waiting for me & half with a sudden influx of business at the end, finds himself guilty to you in a like way. Will you forgive us, both of you, & “not punish us with hard thoughts,” but continue to us those kind ones we have done so little to conciliate?–

May I send a kiss to the unseen babies whom really I wished to see?

Most truly yours

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Casa Guidi.

Monday night.

Tomorrow at nine they were going for the first time to Rome. It was a long way to take a four-year-old in a carriage—they would spend eight days on the road and move into an apartment they’d never seen. It’s an extraordinarily kind note under the circumstances—a new acquaintance, the rush of packing, a child clamoring, all keyed up.

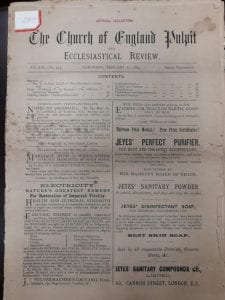

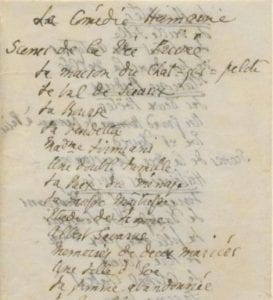

On November 15th, 1853, Mrs. Browning sent a much longer letter to her sister Arabella Barrett in London. She described, at length, a séance at Casa Guidi, and she listed the participants:

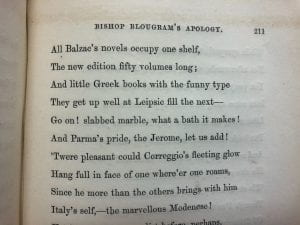

There were Mr & Mrs Tweedy, Americans, (believers in the phenomena) Mr & Mrs Shaw, Mr & Mrs Story, Mr Lytton, Mr Powers, & a Miss Silsbee, a young girl of thirteen, whom Mrs Shaw brought with her on account of the power she had over the tables, & ourselves. Some of us assembled round a small four legged table (with a drawer in it) and after about a quarter of an hour, it moved. I never shall forget the heave it gave under my hand, like a living creature waking from a sleep.

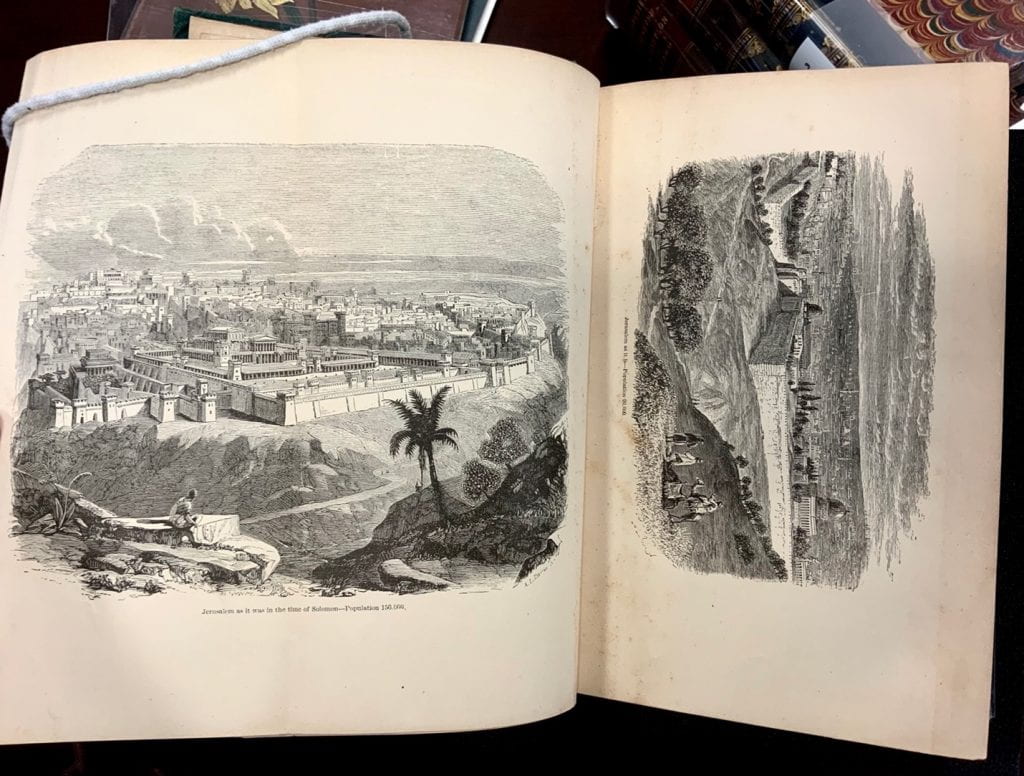

Eleven adults in all, including the Tweedys, parents of the babies she meant to kiss. To seat 11 adults around a small, four-legged table, close enough to hold hands, as was common at seances, would require 11 of one’s smallest chairs. We know what the Casa Guidi drawing room looked like because Robert Browning paid someone to paint it as it was in 1861, the summer Elizabeth died. The walls of the old drawing room were mint green. The curtains were deep red. The chairs in that painting are black and heavy, deeply carved in the gothic style, not at all like the two hummingbird chairs Mrs. Tweedy inherited, which weigh less than seven ounces each. Those two chairs have thin legs, cane seats, and frail backs. Only someone very small and light—like Mrs. Browning—could sit in them without fear of breakage.

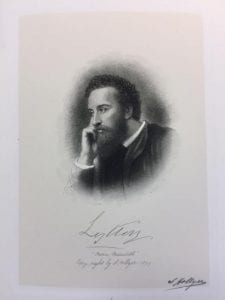

We know many things about the night of the séance. Mary Tweedy, a believer in psychic phenomena, had talked to Mrs. Browning about her babies–the boy who was 15 months old, and the girl, who was just a year older. They had in common the experience of staying in Bagni di Lucca, a town in the mountains. We know that Mr. and Mrs. Shaw are “stupendously rich,” that Mr. Story is a sculptor from Boston, and that his wife, Emelyn, has talked the Brownings into coming to Rome for the winter. The Story and Browning children play together. Hiram Powers is an American sculptor and a believer in the phenomena. Robert Lytton is the youngest adult, a charming, handsome attaché who loves to talk to Mrs. Browning about spiritualism because he, too, is a believer. Mr. Browning, though, is not a believer. He hates seances. When Mrs. Shaw, whom Elizabeth has taken to with characteristic speed, says that the 13-year-old Miss Silsbee is there because “of the power she had over tables” what could her husband say?

In her letter, Elizabeth said the table

turned upon itself, .. & swept us round & round till we were giddy. The motion being over we resumed our seats which had been scattered on all sides in the confusion . . .

The visitors joined hands in the dark. Carriages rolled by. The bell of the chiesa facing their windows rang the hour. Mrs. Shaw, “One of the most interesting women . . . I ever saw, a simple, sweet creature, spiritual in a good sense, looking at these matters reverently & religiously” sat back down and asked

in a dead silence, .. “If any of our friends are here will they signify it by tilting the table?” Instantly the table tilted from one side to the other.

Many things would happen after this night. Amidst all the harried preparations for a 9 o’clock departure, Mrs. Browning would write the kind note to Mrs. Tweedy. It would be taken by hand to Mrs. Shaw at Villino Lustrini. The Brownings and the Storys would go by carriage to Rome. Eight days later, the Story children would catch gastric fever and six-year-old Joe Story would die. The Tweedys would go back to America. Six years after the séance, the Tweedys would visit family in Albany, where diphtheria was spreading. Catharine, aged 8, and Francis, aged 6 years and 11 months, would die three days apart.

The next meeting between the Brownings and Tweedys has no bits of paper to prove it—not yet, anyway. Edmund Tweedy said he went back to Casa Guidi to see the Brownings, and Mr. Browning gave him two chairs from the apartment he was packing up in the summer of 1861, the year Elizabeth died. They crossed the Atlantic and were uncrated in Newport, Rhode Island, where Edmund and Mary Tweedy had adopted a whole family of orphaned relatives to bring up. A story was handed down. “See those chairs? They were given to me by Robert Browning.”

Such light wood. Such narrow spindles. Only Mrs. Browning herself could have sat in them without breaking the legs.

In the 1870s, Americans who sat in parlors in Newport, Rhode Island, knew the poems of Mr. and Mrs. Browning. In the 1880s and ‘90s and even in the early 20th century, after Edmund and Mary died, the chairs would have gained significance when the story was told. They would have changed for the viewer. Here, in this form, is a piece of them, a thing they touched. No one would have had any reason to doubt the story.

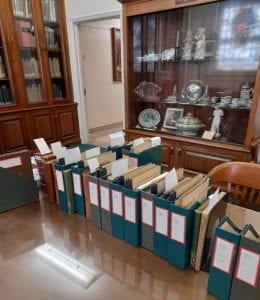

It led to this: Florence Tweedy, aged 73, taking the chairs and their legend to Waco on a winter day in 1968. She must have told the bus driver and the taxi driver, too, what she was doing, traveling like that with two fragile wooden chairs. And yet the taxi driver broke one of them, snapping the back when he unstrapped the chair from his roof. It was all right, though. It could be fixed. An elderly woman had come a long way with her gift. She was shown the bronze doors, the stained glass, the cathedral-like meditation room, the other Browning ephemera. Did she hope for or ask for money? Not that we know of. Did she promise, that day, to bring Mrs. Browning’s handwritten letter? It didn’t come to the library until her daughter, Betty Sykes, the one who was born on the Amazon and educated at Vassar, brought it 30 years later. By then, Florence herself had died.

The 7-ounce chairs sit in the Elizabeth Barrett Browning salon. They face each other behind a velvet rope, where they are protected, like everything in the room, by an alarm system. You could lift them, if you were allowed to lift them, with an outstretched finger. You could hold them both and do no harm to your back. When Christi Klempnauer told me how they had been broken again one day when a maintenance man tripped, I had been reading The Seven Lamps of Architecture by the philosopher, art critic, art teacher, and friend of the Brownings, John Ruskin. It’s a strange book—prophetic, exhortatory, and deeply serious. Ruskin seeks to define the spiritual meaning of architecture, so the “lamps” in his analytical system are moral concepts: Sacrifice, Truth, Power, Beauty, Life, Memory, and Obedience. In the chapter on Sacrifice, which is the first chapter, Ruskin praises the builders of the medieval gate to Rouen:

All else for which the builders sacrificed, has passed away–all their living interests, and aims, and achievements. We know not for what they labored, and we see no evidence of their reward. Victory, wealth, authority, happiness—all have departed, although bought by many a bitter sacrifice. But of them and their life, and their toil upon the earth, one reward, one evidence, is left to us in those gray heaps of deep-wrought stone. They have taken with them to the grave their powers, their honors, and their errors, but they have left us their adoration (23-4).

Although Ruskin is talking about buildings, not furnishings, both are preserved only if we collectively value what they mean. A famous poet can make a chair famous. An immortal poet can make a chair immortal. The older the relic gets, the more miraculous its survival becomes, and a chair escapes the fate of the millions of chairs that become junk every day. Maybe, hopefully, these were the Poets’ Chairs, taken from a house of mourning on a hot summer day in 1861. Maybe, hopefully, they were packed in straw, carried to New England, set up in a parlor, talked about, admired, remembered, and loved. As Ruskin says so beautifully, “They have taken with them to the grave their powers, their honors, and their errors, but they have left us their adoration.”