By Melinda Creech, PhD, Graduate Assistant

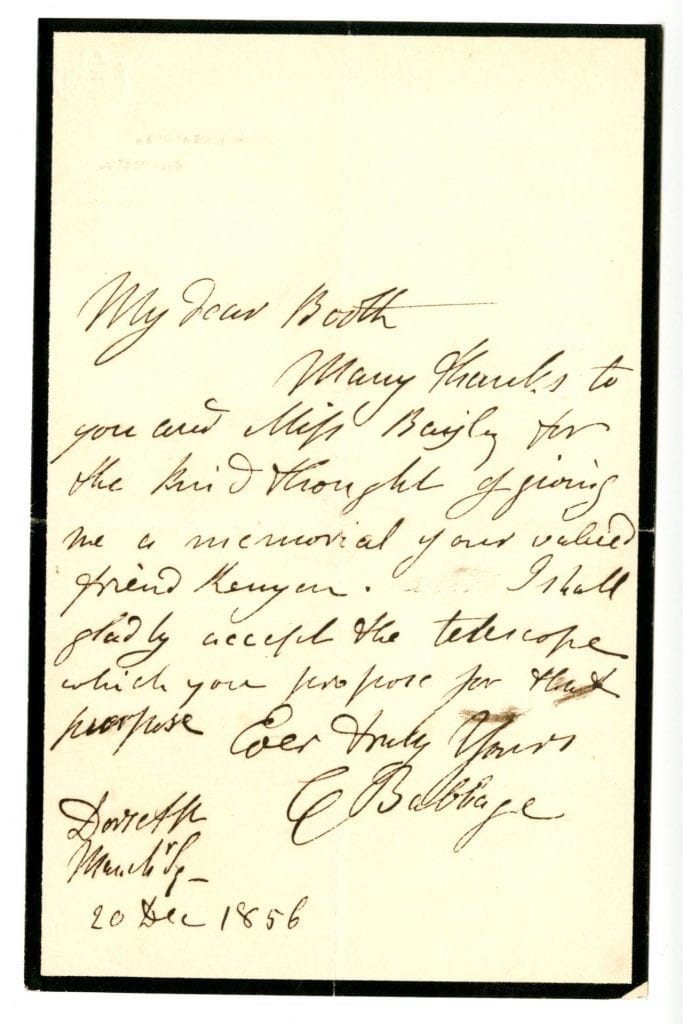

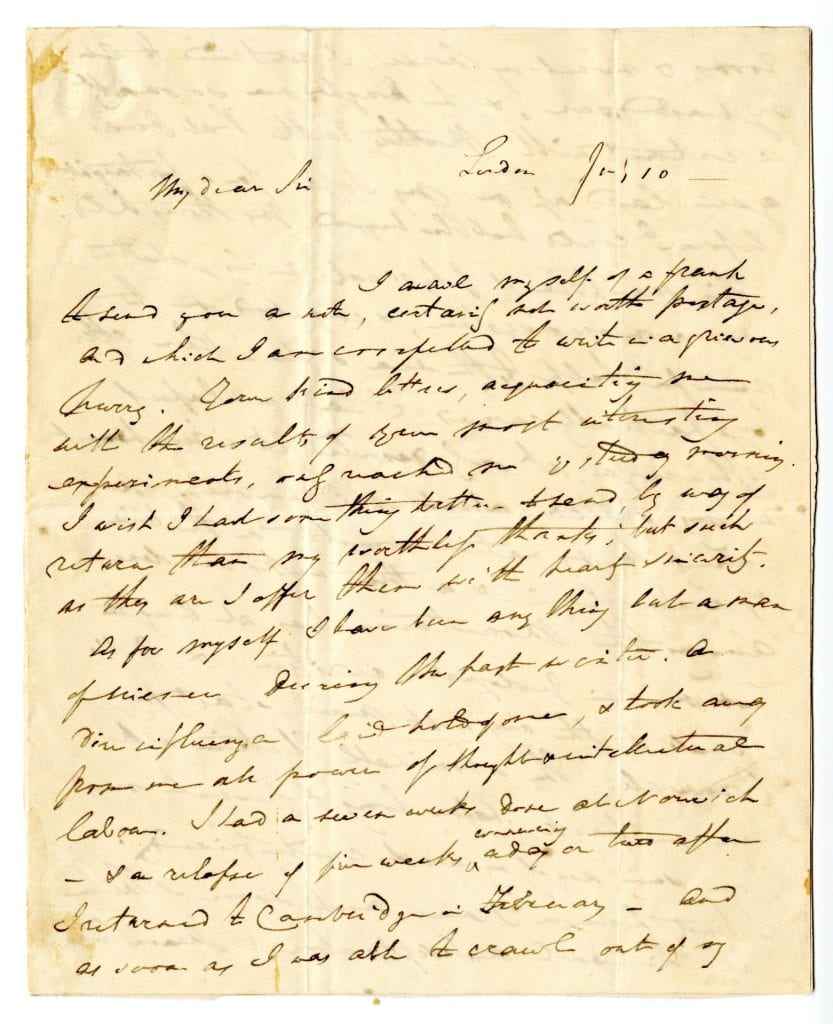

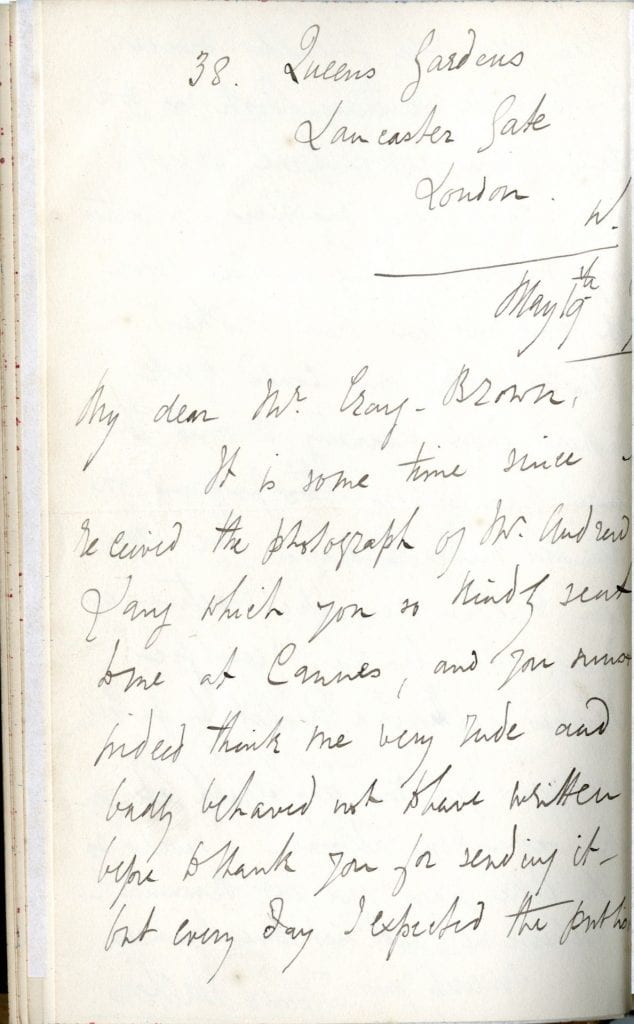

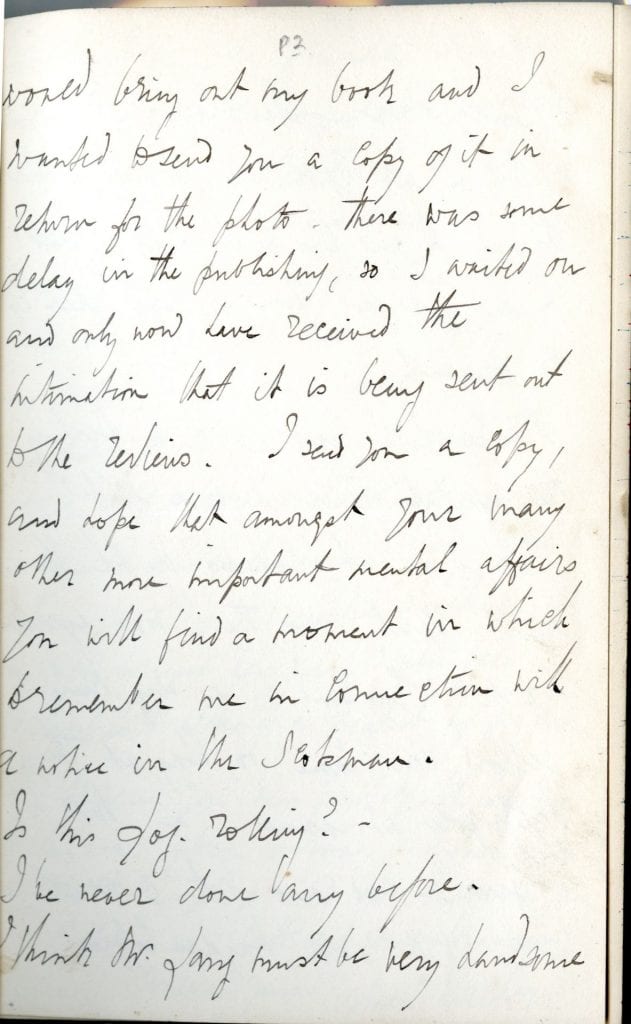

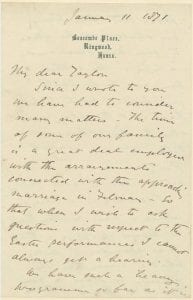

The Armstrong Browning Library is pleased to announce the release of The Victorian Collection online. This new digital collection contains over 3,000 letters and manuscripts connected to prominent and lesser known British and American figures and complements the Armstrong Browning Library’s unparalleled collection of materials relating to the Victorian poets Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The letters and manuscripts in this growing collection can be browsed and searched by date, author, keyword, or first line of text. Letters from the collection are currently on display in Hankamer Treasure Room.

The Armstrong Browning Library is pleased to announce the release of The Victorian Collection online. This new digital collection contains over 3,000 letters and manuscripts connected to prominent and lesser known British and American figures and complements the Armstrong Browning Library’s unparalleled collection of materials relating to the Victorian poets Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The letters and manuscripts in this growing collection can be browsed and searched by date, author, keyword, or first line of text. Letters from the collection are currently on display in Hankamer Treasure Room.

~~~~~

Religion

Many of the letters in the Victorian Collection are from clergymen. The letters run the gamut of different types of Christian faith. There are letters from Catholics, Anglicans, Congregationalists, Unitarians, Universalists, Friends, Brethren, “High” Church, “Low” Church, “Broad” Church, and even Baptists, written by such well-known correspondents at John Henry Newman, Charles Kingsley, William Johnson Fox, Frederick Temple, and John Keble.

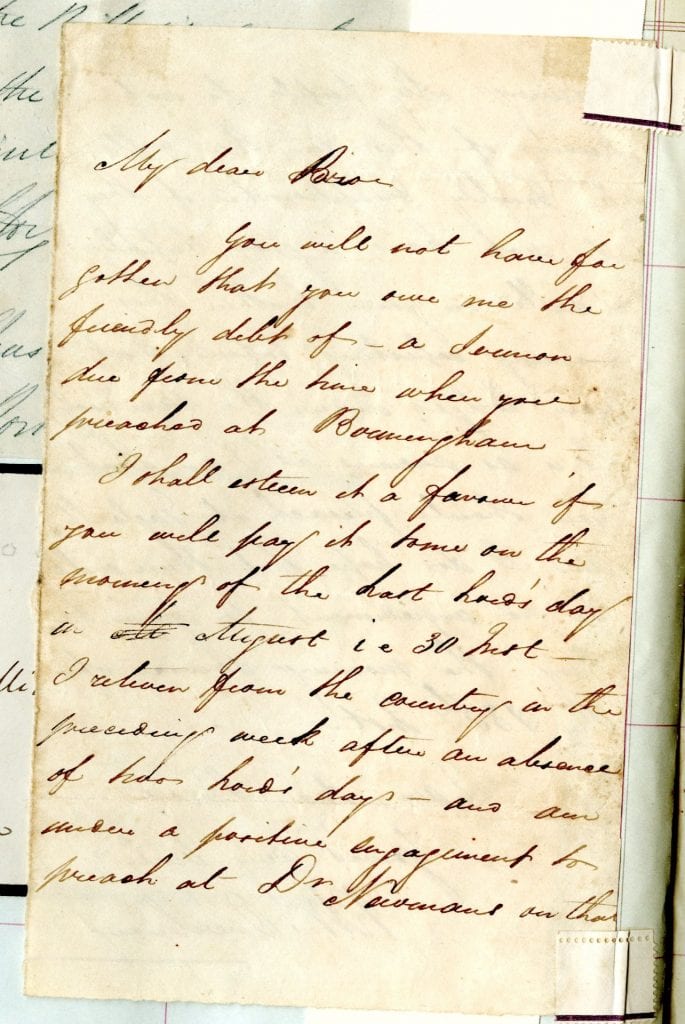

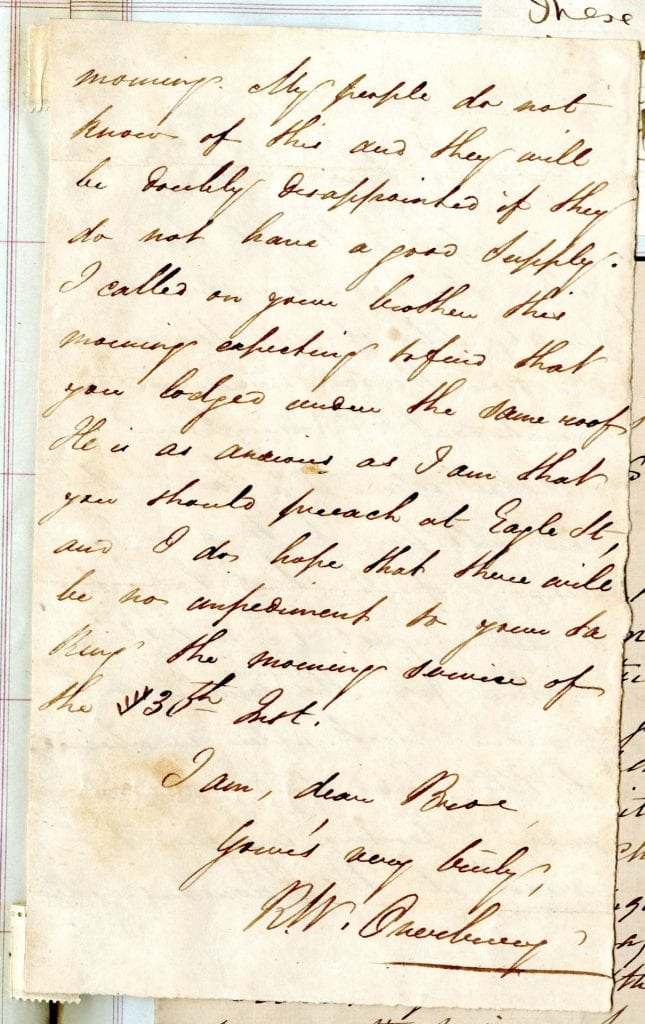

One album of letters that is particularly interesting contains a group of letters collected by Charles Room. Room was a student at the Baptist College in Bristol, presided over the Baptist Church in Evesham, Worcestershire and was assistant pastor to Dr. John Rippon at New Park Street Baptist Chapel in Southwark and minister of the Baptist Church, Meeting House Alley, Portsea.

In this letter R. W. Overbury, pastor of the Baptist Church at Eagle Street, London from 1834 until his death in 1868, invites Charles Room to preach at his church.

*****

Rev. John Rooker, an Anglican minister, was the Director of the Church Missionary Children’s Home, Highbury Grove, Islington, and vicar of St. Peter’s, Clifton Road, Bristol. The letters he collected in the Rooker Album consist of a large number of letters to and from clergy, including this letter from Brooke Foss Westcott, biblical scholar, theologian, Professor of Divinity at Cambridge, and Bishop of Durham. He is perhaps most well known for co-editing, with Fenton John Anthony Hort, The New Testament in the Original Greek in 1881. In this tender letter Westcott answers Rooker’s question about a reference in a book responding:

My great hope is that I may perhaps sometimes encourage a young student to linger with patient faith over the words of Scripture and hear then the message which he needs. We need all of us to write out the promise εν τη υπομονη κτησασθαι τας ψυχας.

[“In patience possess your souls” Luke 21:19]

*****

The ABL has many letters from Anglican bishops, including letters from Christopher Wordsworth, youngest brother of William Wordsworth and Bishop of Lincoln. In this letter to an unidentified correspondent, Wordsworth mentions his publication, “Pastoral to the Wesleyans.”

Letter from Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln to an Unidentified Correspondent. 13 March 1870. Page 1.

Letter from Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln to an Unidentified Correspondent. 13 March 1870. Pages 2 and 3

*****

Comparative religion was an important focus in the nineteenth century as scholars such as Edwin Arnold began to introduce research on world religions. In this letter Emily Marion Harris, English novelist, poet, and educationist, finds a point of comparison between the Book of Common Prayer and prayers that Arnold described in his book, Pearls of Our Faith.

*****

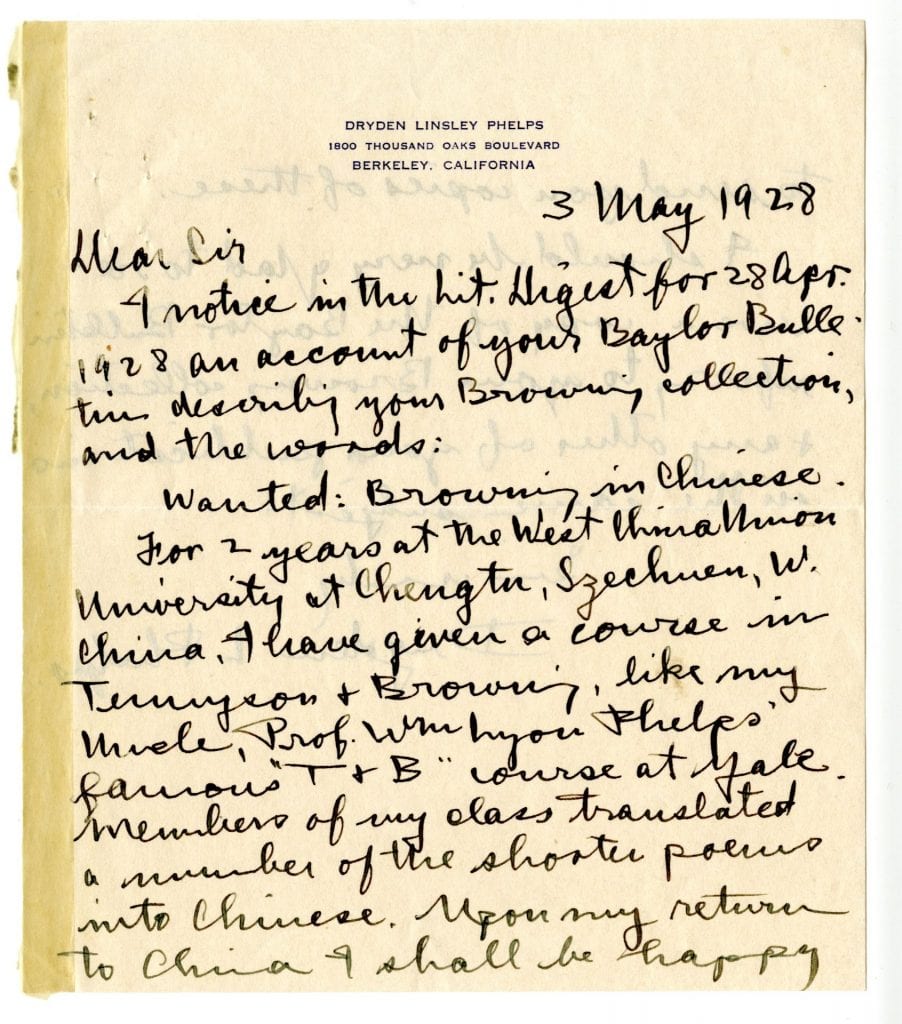

Another interesting set of letters and manuscripts come from Dryden Phelps. Dryden Phelps was the nephew of William Lyon Phelps, Browning scholar and founder of the Fano Club, an annual gathering of Browning aficionados who have visited “The Guardian Angel” painting in Fano, Italy, about which Robert Browning wrote a poem. Dryden Phelps, a missionary to China, reveals in this letter his missions strategy of using the poetry of Browning and Tennyson to introduce his Chinese students to English literature and the tenets of Christianity. Dryden attributes Browning’s popularity in China to the fact that he is “terse, succinct, witty, epigrammatic, unique in a brilliant use of words, profound, a lover of nature, and of human nature, a lover of life.” A Chinese poetry scholar with whom he had studied commented that “he [Browning] is like one of our own poets!” Dryden surmises that one of the highest services we can render China at this moment is to open their eyes to such men as Browning.”

*****

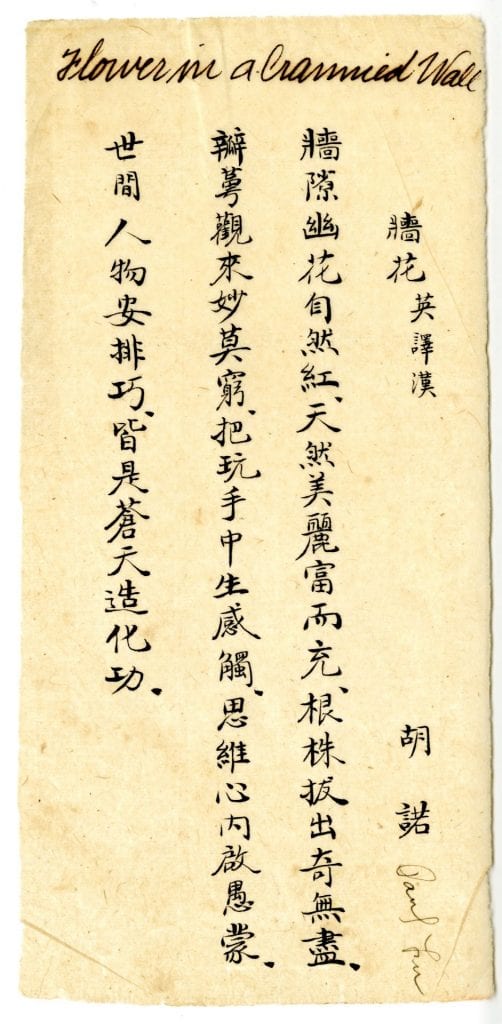

The following manuscripts are Phelps’s students’ efforts to translate the poetry of Browning and Tennyson into Chinese.

“Then Welcome Each Rebuff” by Robert Browning, Translated by an Unidentified Author. Undated. Recto.

“Then Welcome Each Rebuff” by Robert Browning, Translated by an Unidentified Author. Undated. Verso.

*****

Scholars in the nineteenth century were very interested in archeology and reclaiming antiquities. Many letters describe trips to the Middle East to search for treasures. This letter from the Director of the British Museum records a contribution by Mrs. Norris toward the purchase of the Codex Sinaiticus, a manuscript written over 1600 years ago, containing the Christian Bible in Greek, including the oldest complete copy of the New Testament. Edwin L. Norris was a British philologist, linguist, and orientalist who wrote or compiled numerous works on the languages of Asia and Africa. It is unclear what relationship Mrs. R. Norris had to Edwin Norris, if any. Arundell James Kennedy Esdaile was a British librarian, and Secretary to the British Museum from 1926 to 1940.

*****

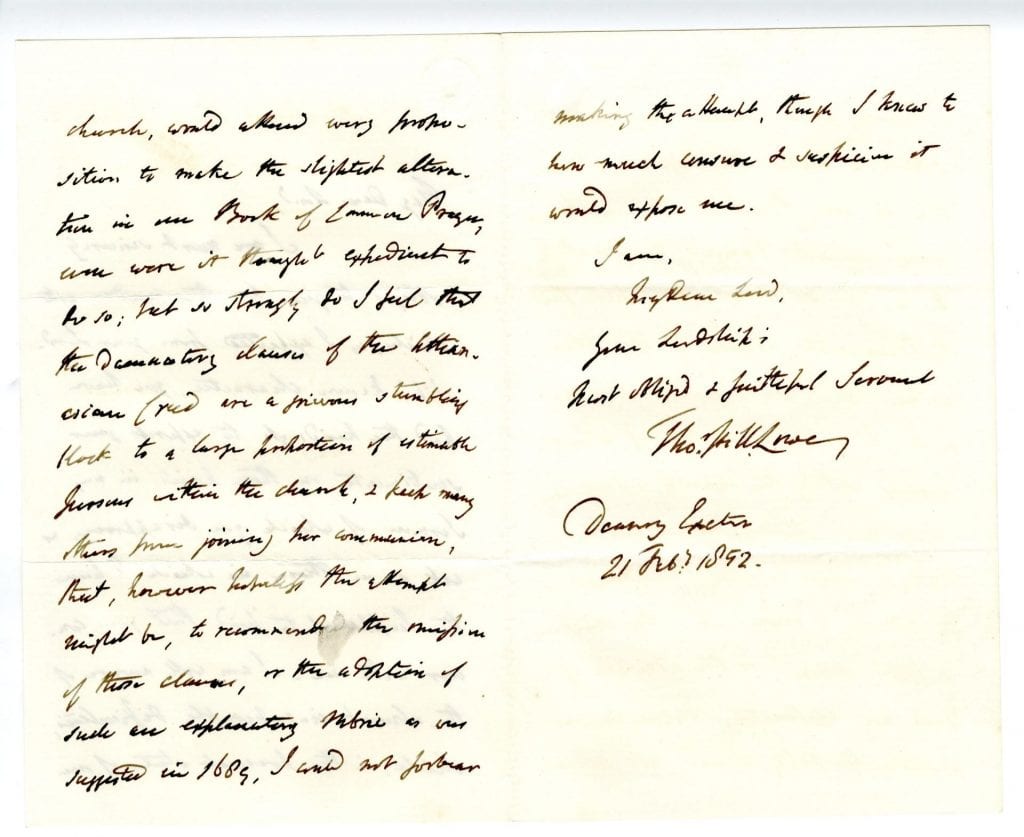

In this letter Thomas Hill Lowe, English cleric and Dean of Exeter (1839-1861), responds to Henry Phillpotts’s criticism of his sermon about changing the Athanasian Creed in the Book of Common Prayer. Henry Phillpotts was the Bishop of Exeter from 1830–1869.

*****

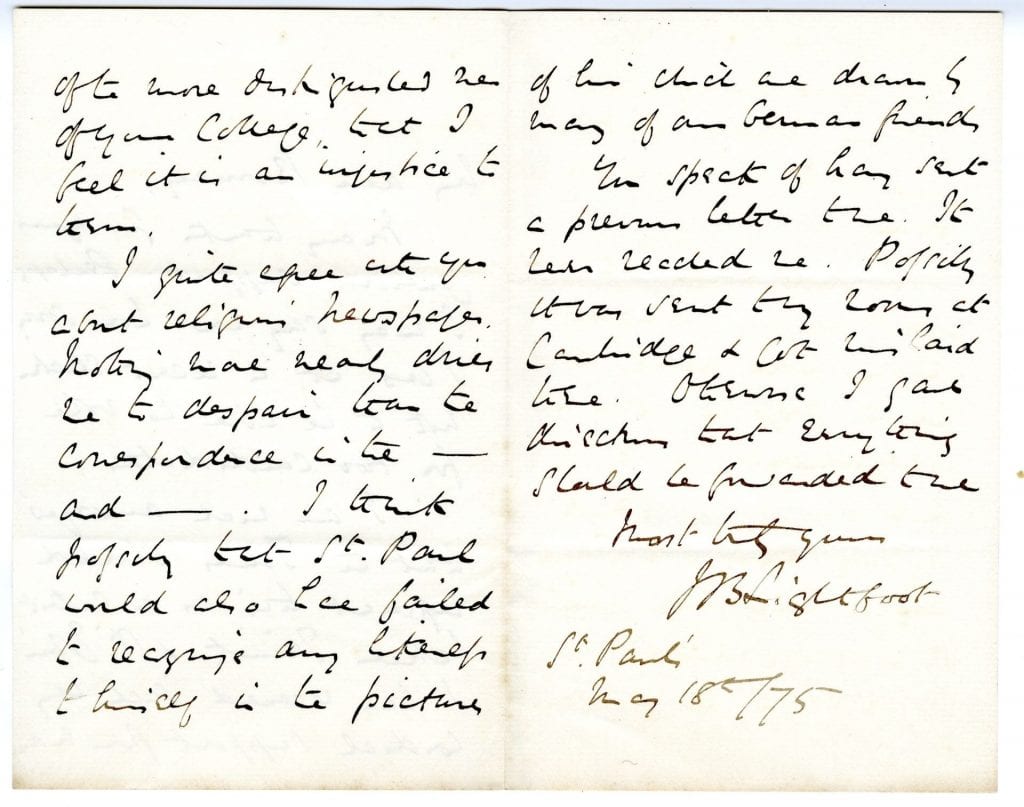

Joseph Barber Lightfoot, an English theologian, Bishop of Durham, and fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, writes to and T. G. Bonney, an English geologist, president of the Geological Society of London, and tutor at St. John’s College, Cambridge, bemoaning the rivalry between Trinity and St. John’s. He is also annoyed by religious newspapers, writing:

I quite agree with you about religious newspapers. Nothing more nearly drives me to despair than the correspondence in the _______ and _____. I think possibly that St. Paul would also have failed to recognize any likeness to himself in the pictures of him which are drawn by many of our German friends

Todd Still, Dean and Professor of Christian Scriptures at George W. Truett Theological Seminary of Baylor University, suggests that one of the newspapers could be The Church Times. He adds, “As for Lightfoot’s remark regarding ‘German friends,’ this is his gracious way of saying that he categorically disagrees with the portrait of St. Paul being painted by F. C. Baur and the Tubingen School.”

Politics

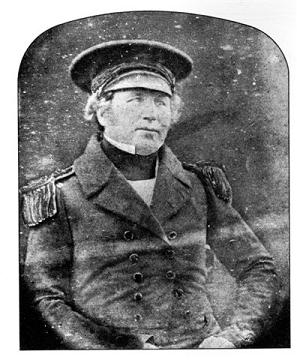

Political letters also comprise a large portion of the Victorian Letters Collection. Our collections contains letters from Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, William Ewart Gladstone, Benjamin Disraeli, and others. The collection also contains many letters from military leaders. The following are only a sampling of the many.

In this letter Lilian Whiting, American journalist, editor, poet, short story writer, and member of the Boston Browning Society, writes about her attendance at a dinner in New York on March 1, 1912 honoring William Howells’s seventy-fifth birthday. Howells was an American novelist, literary critic, and playwright. President Taft and Winston Churchill gave speeches there. Winston Churchill was a young man of thirty-eight who had just become First Lord of the Admiralty the previous year. Whiting comments on and quotes a from Churchill’s speech, rather uncomplimentarily. She writes

Excepting the President, the host, the guest of honor & Mrs. [Alden], – the speeches were unspeakably & ludicrously poor! Winston Churchill’s was as common & as cheap as a table waiter might have made – “As a midshipman”, he preceded to give a chapter of cheap reminiscences of himself – the only link with Mr. Howells being that he had a copy of ‘Silas Lapham’ & “climbed the mast with [it] Howells went up & has been going up ever since” & the copy of ‘Silas’ fell out of his pocket to the deck & that is the only time Howells ever went down!

*****

In this letter to an Unidentified Correspondent, Benjamin Disraeli, then serving his second term as Prime Minister of Great Britain, mentions two residences, Marlboro House, the residence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, and Portland Place, the residence of the unidentified correspondent.

*****

The Armstrong Browning Library has several letters written by William Ewart Gladstone, British statesman and Prime Minister.

This letter was accompanied a pamphlet on vivisection. Gladstone explains that the subject is one “I have never been able to examine with all the care it deserves but I have always had & expressed the opinion that the practice, . . . ought to be confined within the limits of strict & well defined necessity.”

*****

This letter, written to Charles Lee Lewes, may perhaps be referring to Essays and Leaves From a Notebook, by George Eliot, early essays written by Eliot, published posthumously. She had bequeathed all her literary rights to Charles Lee Lewes, the eldest son of George Henry Lewes, her residuary legatee and sole executor of her estate.

*****

In this letter, Gladstone reports that he has no occasion for the works sent by Clement Sadler Palmer, a London publisher and antiquarian bookseller.

*****

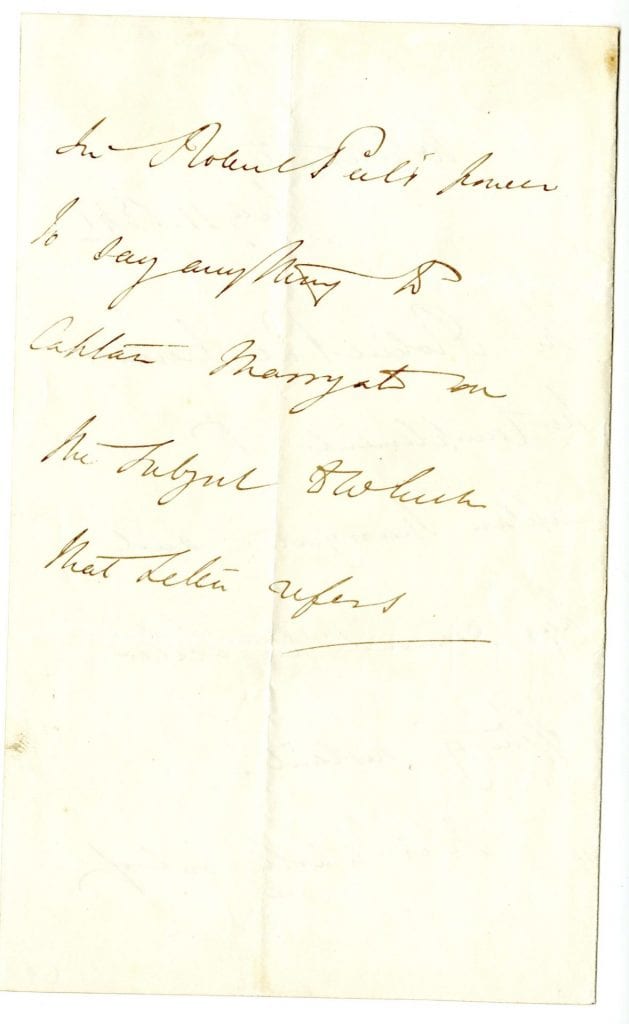

Robert Peel, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for a second term in 1841, writes to Frederick Marryat, a Royal Navy officer and novelist, complimenting him, assuring him that he has received his letter, but stating that it is not in his power to speak to him on the subject of his letter

*****

This manuscript, written by Napoleon III, provides a guardian for the chateau of his mother.

*****

This fragment in German written from Konigsburg is signed by Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, known as the “Romantic” monarch.

*****

In this undated letter, found in the DeCastro Album, William Pitt the Younger, British statesman, declines an “excursion up the river” with Walter Scott, Scottish novelist, poet, historian, and biographer, but invites him to London to discuss some business.

On the verso of the letter is a note in an unidentified hand that reads: “To my father.” ~~~~~For the complete series of blog posts on the Victorian Collection:

- Introducing … The Victorian Collection at the Armstrong Browning Library: A Baylor Libraries Digital Collection

- Introducing … The Victorian Collection at the Armstrong Browning Library: A Baylor Libraries Digital Collection – Science & Exploration

- Introducing … The Victorian Collection at the Armstrong Browning Library: A Baylor Libraries Digital Collection – Religion & Politics

- Introducing … The Victorian Collection at the Armstrong Browning Library: A Baylor Libraries Digital Collection – Theater, Art, & Music

Literary figures represented in the Victorian Collection are covered in the blog series: Beyond the Brownings