By Allison Scheidegger, PhD Student, Department of English, Baylor University

This spring, the Armstrong Browning Library is hosting “Puppy Love: An Exploration of Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships,” an exhibition on dog ownership and depictions of dogs in the Victorian period, with a focus on Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel, Flush. January 15, 2022 – August 15, 2022.

Both print culture surrounding pets and pet ownership in the Victorian era reflect a hunger for status in the midst of increasing affluence. As the middle class became more able to afford luxuries, print culture and pet ownership experienced corresponding economic trends. Middle-class pet owners purchased dogs with carefully documented bloodlines from dog breeders (sometimes called dog “fanciers”). These dogs could become ladies’ lapdogs or gentlemen’s sporting dogs; either way, they offered their owners more than usefulness or affection: they offered prestige. Pedigreed pets became status symbols—no one wanted to be seen walking a mutt! Like owning a lapdog, owning a gilded album revealed the owner’s wealth. The nineteenth century saw the flourishing of ornate collector’s books featuring—or even dedicated to—more frivolous topics like pets. Just as a lady’s lapdog was considered a frivolous pet, such collections would not have been considered serious literature. This blog post highlights some of the ornate artifacts included in the “Puppy Love” exhibit, along with some not included, reconsidering them in the light of Victorian print culture and pet culture.

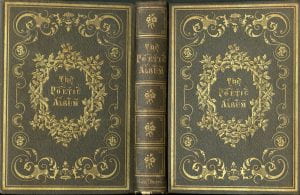

The Poetic Album: Containing the Poems of Alfred Tennyson, Mrs. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Alexander Smith. Philadelphia: Willis P. Hazard, 1854.

The Poetic Album is an excellent example of a collector’s album meant to be a status purchase. The Poetic Album is a collection of “minor poems” (in this case meaning shorter poems) by Tennyson, Browning, and Smith. The covers of The Poetic Album are ornate, and it is extravagantly illustrated with eight engravings of fine ladies. These engravings, which are modeled after illustrations by “the best artists,” according to the book’s title page, have no clear connection with the poems they accompany. In the preface, the publisher Willis P. Hazard classifies these three poets as “three of the best poets of this century.” Hazard also adds that the poems in the collection were selected by “a lady of taste”—a word choice which suggests that purchasing this album could be a way of asserting one’s own gentility.

In a decorative collection like this one, there is room for pet poems which might be considered frivolous elsewhere. Both of E. B. Browning’s Flush poems—“Flush or Faunus” and the earlier “To Flush, My Dog”—appear in this collection, whereas in many collections of Browning’s work only “To Flush” is included. Browning’s note below “To Flush” acknowledges both the personal and monetary value of Flush. Customers who could afford to purchase this ornate gift book likely could also afford the expenses of buying and caring for a purebred dog, and therefore would be interested in such poems.

- The Poetic Album. 1854.

- The Poetic Album. 1854.

- The Poetic Album. 1854.

Findens’ Tableaux: A Series of Picturesque Scenes of National Character, Beauty, and Costume. Edited by Mary Russell Mitford. Engraved by William and Edward Finden. 1838.

Findens’ Tableaux is a collection of illustrations and stories edited by Mary Russell Mitford, the friend who would give E.B. Browning her spaniel Flush in 1841. Like The Poetic Album, Findens’ Tableaux presents ornate illustrations. Each engraved illustration becomes a tableau, or still picture, that acts out, in freeze-frame, the story or poem it accompanies. The 1838 volume of the Tableaux focuses on stories set in various countries of the world. “Scotland: Sir Allan and his Dog,” the story featured here, was written by Mitford herself. Although the buyers of such a collection would have been very comfortably wealthy, Mitford herself struggled financially (Taneja 131-2). For “ladies of taste” who lacked money, editing collections like the Tableaux and The Poetic Album became a helpful source of income.

- Finden’s Tableaux. 1838.

- Finden’s Tableaux. 1838.

- Finden’s Tableaux. 1838.

- Finden’s Tableaux. 1838.

- Finden’s Tableaux. 1838.

- Finden’s Tableaux. 1838.

I considered Findens’ Tableaux for inclusion in the exhibit, but ultimately had to omit it due to space constraints: the book is 15 inches tall by 11 ½ inches wide.

Friendship’s Forget-Me-Not. London: Thomas Nelson, 1849.

On my trips to the ABL stacks, I noticed that ornamental books—much like prized breeds of dog—tend to be either very large or very small. On the opposite end of the size spectrum from Findens’ Tableaux is Friendship’s Forget-Me-Not, measuring 4 ¾ inches tall by 3 ¼ inches wide. Friendship’s Forget-Me-Not was designed to be a memento given to a friend upon parting. This book was not included in the exhibit because it reprints E. B. Browning’s most frequently anthologized dog poem, “To Flush, My Dog”—a very appropriate choice for a collection of poems sharing the themes of friendship and gifts. Like this ornate gift book, Flush was an extravagant gift between friends.

- Friendship’s Forget-Me-Not. 1849.

- Friendship’s Forget-Me-Not. 1849.

- Friendship’s Forget-Me-Not. 1849.

As the detailed description of the poem establishes, Flush is a highly decorative spaniel: Browning revels in his “fringed” feet, “tasselled ears,” and “silver-suited breast.” In a similar way that the gilding of Friendship’s Forget-Me-Not can indicate the quality of a friendship, Flush’s beauty serves to demonstrate the quality of Browning’s relationship with Mitford and, in turn, to enhance Browning’s relationship with Flush. Although linking friendship with consumerism in this way might seem problematic, in “To Flush” at least Browning affirms that love, not appearance, is the primary thing.

While Mary Russell Mitford and Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote dog literature for adults (albeit “light” literature), the majority of animal writing throughout the 1800s is written for children. The “Puppy Love” exhibit highlights several examples of animal writing in children’s literature. The following two collections (which appear in the exhibit) focus exclusively on animal stories and target an audience of children rather than adults. But as with the ornate collector’s books written for adults, publishers marketed these colorfully illustrated and gilded books in the hope of inducing rich parents to buy.

Aunt Louisa’s Choice Present: Comprising Famous Horses, Noted Horses, Famous Dogs, Noted Dogs (or Horses & Dogs). Illustrated by John Frederick Herring, Sr., and Sir Edwin Landseer. Twenty-Four Pictures Printed in Colours by J. Butterfield. London: Frederick Warne and Co., 1876.

This decorative collection presents 24 color pictures of horses and dogs, printed by J. Butterfield from illustrations by Herring and Landseer, who were prominent animal painters of the Victorian period. Although as the preface notes, these paintings were not originally intended to be paired with text, the accompanying narratives comment on society through the stories of these animals, with the intent of making these images interesting and educational for children. The displayed story questions whether the “high life” of a lady’s pet is the life this dog would choose.

- Horses and Dogs. 1876.

- Horses and Dogs. 1876.

- Horses and Dogs. 1876.

- Horses and Dogs. 1876.

- Horses and Dogs. 1876.

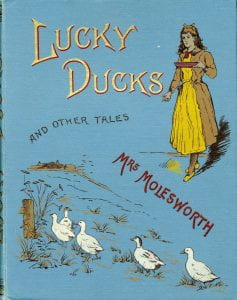

Mary Louisa Molesworth’s Lucky Ducks and Other Stories. Illustrated by W. J. Morgan. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1891.

Mary Louisa Molesworth’s story of the pampered, naughty dog Dandy parallels the story of Fido in Horses and Dogs: a lady’s dog must live in confined circumstances when he would like to run in the countryside and chase geese. Though Molesworth invites children to notice how pets’ desires and emotions might differ from their owners’, she characterizes Dandy’s actions as naughtiness rather than natural canine behavior. She does not acknowledge that perhaps Dandy’s “lapdog existence” is not best for him, and thus tacitly affirms the upper-class treatment of lapdogs. Although Molesworth herself was born into middle-class circumstances, she tended to write about upper-class concerns (Avery). For a generation of middle- and upper-class children, Molesworth’s animal stories reinforced popular assumptions about status, class differences, and the treatment of animals.

Works Cited

Aunt Louisa’s Choice Present: Comprising Famous Horses, Noted Horses, Famous Dogs, Noted Dogs (or Horses & Dogs). Illustrated by John Frederick Herring, Sr., and Sir Edwin Landseer. Twenty-Four Pictures Printed in Colours by J. Butterfield. London: Frederick Warne and Co., 1876.

Avery, Gillian. “Molesworth [née Stewart], Mary Louisa (1839–1921), Novelist and Children’s Writer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-37776

Findens’ Tableaux: A Series of Picturesque Scenes of National Character, Beauty, and Costume. Edited by Mary Russell Mitford. Engraved by William and Edward Finden. 1838.

Friendship’s Forget-Me-Not. London: Thomas Nelson, 1849.

Molesworth, Mary Louisa. Lucky Ducks and Other Stories. Illustrated by W. J. Morgan. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1891.

The Poetic Album: Containing the Poems of Alfred Tennyson, Mrs. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Alexander Smith. Philadelphia: Willis P. Hazard, 1854.

Taneja, Payal. “Gift-Giving and Domesticating the Upper-Class Pooch in Flush.” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, vol. 49, no. 1, 2016, pp. 129-144.

Read more in this series of blog posts about the exhibit “‘Puppy Love’: An Exploration of Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships“:

- Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships in the ABL’s Archive (March 16, 2022)

- “Puppy Love”: Inside the Process (April 13, 2022)

- Reception of E.B. Browning’s and Virginia Woolf’s Dog Writing (June 15, 2022)

- “Puppy Love”: What I Learned Through the Process (July 13, 2022)

- “Puppy Love” Closing Announcement (August 3, 2022)