By Allison Scheidegger, PhD Student, Department of English, Baylor University

This spring, the Armstrong Browning Library is hosting “Puppy Love: An Exploration of Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships,” an exhibition on dog ownership and depictions of dogs in the Victorian period, with a focus on Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel, Flush. January 15, 2022 – August 15, 2022.

Curious about what their pets were thinking and feeling, Victorian authors lent animals emotions, thoughts, and even voices in their writing. Elizabeth Barrett Browning tried twice to represent Flush’s thoughts and emotions in poetry, and included tales of his antics in her letters. Although nineteenth-century literature about pets was often dismissed as frivolous, the issues raised were serious. As the increasing wealth of middle- and upper-class Victorians enabled them to purchase pets, a surge in dog ownership brought accompanying problems of misguided canine care and the use of pedigreed dogs as status symbols. Meanwhile, dognapping rings sought to profit from owners’ emotional and economic investment in their dogs. The stories of Flush and other Victorian dogs reveal both the possibilities and problems of pet ownership. Interacting with pets as fellow-creatures can increase humans’ capacity to give and receive love; however, the relationship is always imperfect. Like Victorian pet owners, we struggle at times to understand and meet our pets’ needs.

Flush and Friendship

The exhibition is divided into three sections. The first section focuses on E. B. Browning’s relationship with Flush and how that relationship fostered other friendships. Flush became a living symbol of the friendship between Browning and fellow author Mary Russell Mitford. When Mitford sent Flush as a gift to comfort Browning after the death of her brother Edward, Flush succeeded in rousing Browning from deep depression. Although as an invalid Browning lived a secluded life, she communicated with Mitford and other friends through letters in which she described Flush’s looks, emotions, and antics.

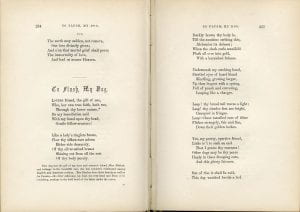

Browning first shared Flush with her reading public through the poem “To Flush, My Dog.” After reading “To Flush ,” one of Browning’s fans, fellow poet Thomas Westwood, took courage to begin corresponding with Browning. In the first section of the exhibit, a pair of letters between Browning and Westwood reveals how Flush became a mediator between Browning and the outside world—owning a dog was a shared experience that enabled Browning to connect with others.

Social Issues: Breeding and Dognapping

The second section examines cultural issues that arose from the pedigreed pet craze in Victorian England. As more middle- and upper-class citizens became dog owners, interest in dog breeding grew exponentially. Although authors like Eliza Cook insisted that a mutt without a pedigree could be as lovable and loyal as an expensive spaniel, for many Victorians, a pedigreed pet was a status symbol. Valuable ladies’ pets like Flush led lives of luxurious confinement, eating sweets and lying on couches nearly all day. In addition to their unhealthy lifestyles, on their brief walks, these pets faced the threat of dognapping. Because the rich lived alongside the poor in London, poorer Londoners watched the rich parade their expensive pets along the sidewalks. London dognapping gangs grew wealthy by capturing pedigreed dogs and threatening to kill them unless their owners paid a ransom. E. B. Browning’s spaniel Flush became a victim of these socioeconomic trends, as Browning announces in a letter to her cousin John Kenyon.

- E. B. Browning’s letter to John Kenyon. 2 September 1846.

- E. B. Browning’s letter to John Kenyon. 2 September 1846.

- E. B. Browning’s letter to John Kenyon. 2 September 1846.

- E. B. Browning’s letter to John Kenyon. 2 September 1846.

Depicting Animals

The third section considers broader trends of animal writing in the nineteenth century. In the Victorian period, stories about pets were often written for the purpose of teaching children. Because to Victorian pet owners, pets seemed nearly human in their personalities and emotional responsiveness, many of these stories engage in anthropomorphism, the imagining of animals as human. Writers of animal stories experimented with giving animals voices and perspectives that tend to resemble human voices and perspectives. While many nineteenth-century authors like Mary Louisa Molesworth seem confident in their ability to accurately portray pets’ unique personalities, modern authors such as Virginia Woolf still struggle with the question of how to represent pets’ thoughts and feelings.

- Dandy’s Revolt in Molesworth’s Lucky Ducks and Other Stories. 1891. Pg. 90.

- Dandy’s Revolt in Molesworth’s Lucky Ducks and Other Stories. 1891. Pg. 91.

- Woolf’s Flush: A Biography. 1933. Pg. 26.

- Woolf’s Flush: A Biography. 1933. Pg. 27.

- “The Back Bedroom,” in Woolf’s Flush: A Biography. 1933.

Works Cited

Browning, Elizabeth Barrett. Letter to John Kenyon. 2 September 1846. Browning Correspondence.

—. “To Flush, My Dog.” In The Poetic Album: Containing the Poems of Alfred Tennyson, Mrs. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Alexander Smith. Philadelphia: Willis P. Hazard, 1854.

Molesworth, Mary Louisa. Lucky Ducks and Other Stories. Illustrated by W. J. Morgan. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1891.

Woolf, Virginia. Flush: A Biography. London: Hogarth Press, 1933.

Read more in this series of blog posts about the exhibit “‘Puppy Love’: An Exploration of Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships“:

- “Puppy Love”: Inside the Process (April 13, 2022)

- Victorian Print Culture and Pet Culture (May 18, 2022)

- Reception of E.B. Browning’s and Virginia Woolf’s Dog Writing (June 15, 2022)

- “Puppy Love”: What I Learned Through the Process (July 13, 2022)

- “Puppy Love” Closing Announcement (August 3, 2022)