By Jerome Wynter, PhD, Adjunct Assistant Professor, BMCC, City University of New York

The Armstrong Browning Library (ABL) at Baylor University boasts an archive of nineteenth-century poetry entitled “The Minor English Poets’ Collection.” Purchased in 1986 from Pickering and Chatto, it contains 249 works of verse and dramatic verse published in the Age of Queen Victoria (1837-1901). My examination of this little-explored collection reveals that the title appears to be a misnomer. The collection features the poetry of authors whose writings appeared in print only occasionally, such as the members of the Glasgow Ballad Club, John Stuart Blackie (1809-1895), John Christopher Fitzachary, James Rennell Rodd (1858-1941) and Charles Whitworth Wynne (1869-1917). But it also includes the works of poets who were well established in their day and who have received serious critical attention in ours, including George Meredith (1828-1909) and William Ernest Henley (1849-1903). Many of the poets also identify themselves as Scots and Irish in their prefaces, and several of the poems are composed in a regional dialect of Celtic or Gaelic origin.

This anomaly notwithstanding, the collection is a rich resource. My purpose in exploring the work of these mid- to late-Victorian “minor” poets was to discover their contribution to the aesthetic, political and social poetic practices to the literature and culture of the period. Kirstie Blair reminds us that with the recovery of so many minor poets “much remains to be said about them and their importance in the literary cultures of their time, not to mention the political, social and religious contexts” (2013: 3). Blair is referring to laboring- and working-class poets, but her remark points to the need for a greater renewal of interest in the study of the work of Victorian minor poets of all social classes.

Reading upwards of twenty volumes of poetry, I investigated how these “minor English” poets might be a corrective to the viewpoint of the canonical poets. I charted the broad themes of daily life. Invariably, these are concerned with poverty, economic disparity between classes, death and loss, and the Christian faith. I also explored the poets’ engagement with local and contemporary politics, national histories and the representation of nature and the environment. It is the final two of these themes that I wish to focus on briefly, paying special attention to two works of ecocritical poetry.

National Memory

Many of the poems in the archive focused on national history with a concentration on the themes of national memory, patriotism and nostalgia for bygone times. There are tributes to English and Scottish heroes, both historical and literary: Sir Francis Drake (1540-1596), Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), the Duke of Wellington (Arthur Wellesley, 1769-1852), Robert Burns (1759-1796) and Lord Alfred Tennyson (1802-1892). Irish nationalism, on the other hand, is revived mainly through the poetic treatment of legends. In a patriotic homage to Sir Francis Drake in Ballads of the Fleet and Other Poems (1897), for example, Rodd represents the infamous pirate as a hero whose life on the seas is peerless, in “San Juan De Lua” written in two-line stanzas of heroic couplets. In another unapologetically patriotic poem Home Poems (1899), Walter Earle congratulates England for its successful wars, colonial history, and territorial expansion. His goal, it seems, is to bolster national pride and self-confidence. In one poem entitled “The New Century,” the speaker announces, “Well-done, good Land! thou hast another hundred years to go” (Stanza 4), concluding that “So shall our Empire be the Champion of the Right, – / Our Flag unstained, our Name upheld; – then come what may” (Stanza 6). Remarkably, Earle’s poems ignore the effects of colonization and England’s wars during the century.

Ecocritical Poetry

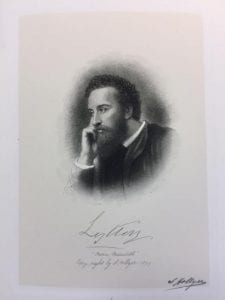

Poets whose work engages with nature and environment are far less nationalistic. Many of their poems evoke Romantic tropes of nature and the wilderness, but few could be considered ecocritical poetry, which The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (2012) defines as “related to the broader genre of nature poetry but can be distinguished from it by its portrayal of nature as threatened by human activities.” Two notable examples of ecocritical writing that denounce the threat human activities posed to the non-human world are the poems After Paradise or Legends of Exile and Other Poems (1887) and Ad Astra (1900) by Robert, Earl of Lytton (1831-1891) and Whitworth Wynne, respectively. Both poets tackle man’s progress and degradation of the natural world, though they do not necessarily foreground the natural world or wilderness. Commenting on poetry of this kind, Karla Armbruster and Kathleen R. Wallace assert that one of the ecocritic’s most important tasks today is to consistently “address a wider spectrum of texts” that are less obviously about “natural” landscapes (2001:2).

This hybrid poetry is represented by the work of both Lytton and Wynne. Writing under the pseudonym Owen Meredith, Lytton’s title poem “After Paradise” comprises several independent sections. The first, The Titlark’s Nest: A Parable, is a fifteen-stanza modified form of the ottava rima that obliquely celebrates nature’s reclamation of the space occupied by a now abandoned temple. Colossally and splendidly built on a Greek island, it had displaced the whistling meadow pipit or titlark, the Tmetothylacus tenellus. The first stanza describes the church “high on the white peak of a glittering isle” (Stanza 1). However, it now stands “a ruin’d fane within a wild vine’s bowers,” a vine that muffles “its marble-pillar’d peristyle” (Stanza 1). Beautifully rendered, these lines capture the irony of a once opulent place of worship, “girt by priests and devotees” where “[a] god once gazed upon the suppliant throng” (Stanza 3) that has been left to rot:

The place was solitary, and the fane

Deserted save that where, in saucy scorn

Of desolation’s impotent disdain,

The reveling leaves and buds and bunches born

From the wild vine along a roofless lane

Of mouldering marble columns roam’d, one morn

A titlark, by past grandeur unopprest,

Had boldly built her inconspicuous nest. (Stanza 2)

The stanza juxtaposes the dead and desolate church building with the emerging life of plant (“buds and bunches born”) and animal (“A titlark”). The diction is one of degradation and the tone is resentful. This is conveyed through the alliterative “saucy scorn / Of desolation’s impotent disdain.” However, this tone gives way to another contrasting and conflicting one: an expression of triumph enacted by the “revelling” of the leaves amid the “buds and bunches born / From that wild vine.” The poet reconciles the former oppressive “grandeur” of the temple with the victory of “one small bird” (Stanza 3). This is a poem of contrasts and repetition, and Lytton seems to emphasize the success of the non-human world over the intrusiveness of man-made structures and the degradation which follows their reckless desolation. In Whitworth Wynne’s Ad Astra, the speaker reflects on man’s torrid relationship with God and nature, and the disastrous effects of his achievements and progress in the last few decades of the expiring century. Written in iambic pentameter, the poem consists of 227 seven-line stanzas, rhyming ababbcc. The speaker is critical of the many advancements man has made in the last decade, especially in electricity in 1887, and ponders:

XXXI

And Man, to what achievements doth he move!

Who shall foretell his boundless destiny!

Out of the earth what untold treasure-trove!

What realms await him in the trackless sky!

The stored lightnings at his bidding fly,

The circuits of the World their bounds decrease

Before the smile of universal Peace.

Initial Findings

Lytton’s and Whitworth Wynne’s ecocritical poetry aside, the majority of the volumes in the Collection, especially by the 1890s poets, that I read reveal a widespread engagement with patriotism and celebration of national history, foreshadowing Rudyard Kipling’s poetic response to empire in The Five Nations (1903). Several poets commemorate the life of Lord Alfred Tennyson (“mighty of heart or brain”), some employing the language of empire to represent the poet laureate as “Warders of Empire’s outposts.” These are but a few of the many themes to be explored in “The Minor Poets’ Collection.” Overall, my initial investigation shows that the “minor English poets,” writing in the final two decades of the nineteenth century, present no clear break with the poetry of the canonical poets of the period, with some original reviewers commenting that the work of Lord Lytton and Whitworth Wynne (pseudonym for Charles Cayzer) is imitative of Tennyson and Robert Browning.

Through the generosity of the Armstrong Browning Library at Baylor University, which awarded me a visiting research fellowship in 2019, I am grateful for the first privilege of sampling this impressive collection of writings by “minor English poets” as part of a second major project. I thank all who made my time at the ABL and Baylor a success, in particular Christi Klempnauer, who was always available to make sure my needs were well seen to, and Assistant to the Curators Melvin Schuetz and the Director Jennifer Borderud.

Works Consulted

Armbruster, Karla, and Kathleen R. Wallace, eds. (2001). Beyond Nature Writing: Expanding the Boundaries of Ecocriticism. (Charlottesville, NC and London: University Press of Virginia).

Blair, Kirstie, and Mina Gorji, eds, (2013). Class and the Canon: Constructing Labouring-Class Poetry and Poetics, 1750-1900. (London: Palgrave Macmillan. Introduction, 1-15).

Boos, Florence (2002). “Working-Class Poetry,” in Richard Cronin, Alison Chapman and Antony H. Harrison, eds., A Companion to Victorian Poetry. Malden, Mass. and Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., pp. 204-228.

Hoppen, K. Theodore. (1998). The Mid-Victorian Generation, 1846-1886. (Oxford: UOP).