By Lindsay Wells, PhD Candidate, Department of Art History, University of Wisconsin-Madison & Dissertation Fellow, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library

Lindsay Wells, PhD Candidate, Department of Art History, University of Wisconsin-Madison & Dissertation Fellow, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library

When we think about Victorian houseplants, the phrases fern craze and orchidmania likely spring to mind. Or maybe it is images of palm-festooned parlors and conservatories, such as those found in the colorful paintings of James Tissot. Many forms of houseplant horticulture can trace their roots back to nineteenth-century Britain, where ferns, orchids, and palms enjoyed perennial favor amongst home gardeners. But what about the humble cactus?

At first glance, cacti and other succulents may seem more of a contemporary phenomenon than a Victorian one. From echeverias and jade plants to sedums and aloes, these plants have become the darlings of many a Twitter feed and Instagram account devoted to indoor gardening. [Figures 1-3]

- Fig. 1, Potted cacti for sale at the Dane County Farmers’ Market in Madison, Wisconsin. Image copyright Lindsay Wells.

- Fig. 2, Potted cacti at an open-air market in Florence, Italy. Image copyright Lindsay Wells.

- Fig. 3, Succulent display in a Manhattan apartment. Image copyright Lindsay Wells.

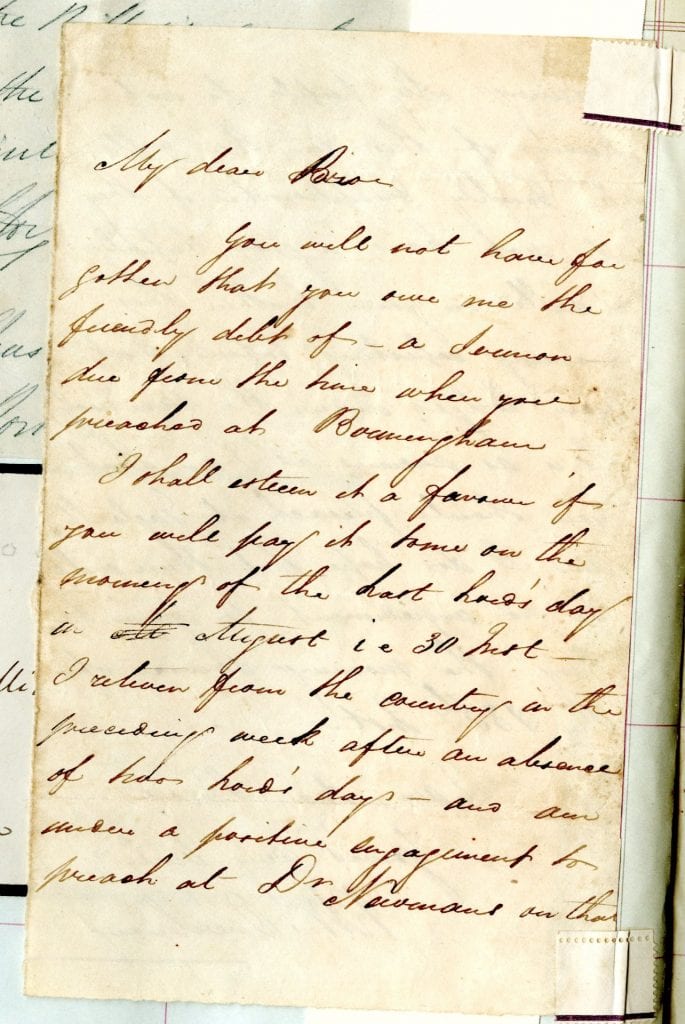

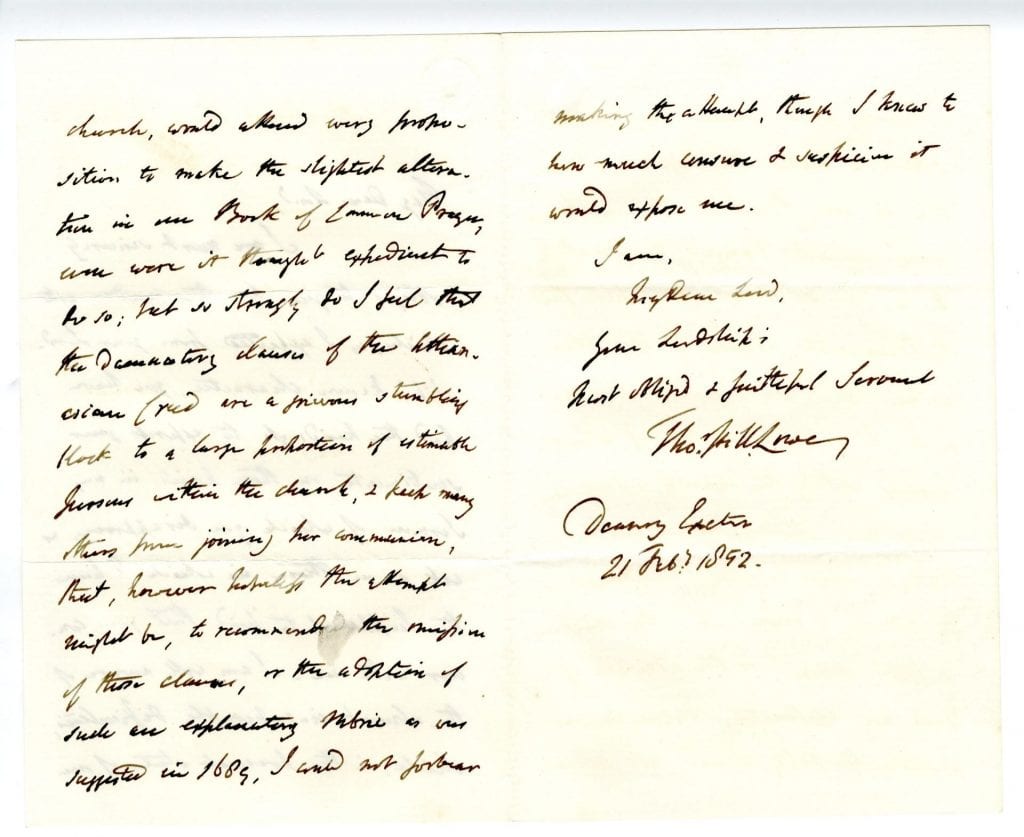

- Fig. 4, Title Page to Jane Loudon’s Practical Instruction in Gardening for Ladies (1841), Armstrong Browning Library

Yet succulents were also grown extensively in the nineteenth century, when, as Andreas Stynen notes, the modern concept of “houseplants” first emerged (219). In her groundbreaking guide to indoor gardening, Flora Domestica (1823), Elizabeth Kent included a lengthy entry on the “Great-flowered Creeping Cereus”—a type of cactus renown for its bright blossoms (84). The horticultural polymath Jane Loudon also wrote about the merits of cereus cacti, which she described in her Practical Instruction in Gardening for Ladies (1841) as “singular looking plants” that “should be kept in only green-house heat” (394). [Figure 4] Meanwhile, terrarium inventor Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward recommended “Aloes, Cactuses, Mesembryanthemums, and other succulent plants” to readers of his 1842 treatise on ornamental plant cases (60), as did houseplant expert Elizabeth A. Maling, whose handbook In-Door Plants (1862) featured a pink-flowering cactus in its frontispiece. As these and countless other texts demonstrate, the popularity of potted succulents has proved as hardy and long-lasting as the plants themselves.

My doctoral dissertation, “Plant-Based Art: Indoor Gardening and the British Aesthetic Movement,” explores how houseplant horticulture influenced botanical imagery in Victorian painting and literature. During my recent fellowship at the Armstrong Browning Library, I identified and analyzed various houseplants that found their way into nineteenth-century poems, particularly those from the Library’s 19th Century Women Poets Collection. Orchids and geraniums are recurrent motifs in these works, as are ferns, palms, and other leafy greens commonly associated with the Victorian parlor garden. [Figure 5]

Fig. 5, Red Geranium watercolor from E.F.C.’s Flowers Culled from Browning’s Poems (no date), Armstrong Browning Library

However, I also encountered a surprising number of poems about succulent plants.

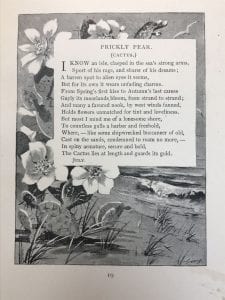

While some of these works, such as Emily Shaw Forman’s “Prickly Pear (Cactus)” (1895) or Ina Coolbrith’s “Retrospect (In Los Angeles)” (1895), describe cacti growing in the wild or in outdoor gardens, others reference specimens that the Victorians typically kept indoors. [Figures 6-7]

- Fig. 6, Cover of Emily Shaw Forman’s Wild-Flower Sonnets (1895), Armstrong Browning Library

- Fig. 7, Emily Shaw Forman’s “Prickly Pear (Cactus),” from Wild-Flower Sonnets (1895), Armstrong Browning Library

These included the aloe, the night-blooming cereus, and the cactus speciosissimus. By comparing these poems to nineteenth-century gardening books, I realized that Victorian poets and horticulturalists valued many of the same aesthetic characteristics of the succulent family. In what follows, I want to highlight some of the poems I examined at the Armstrong Browning Library that illustrate how different nineteenth-century writers took advantage of the expressive potential of succulents in their work.

Much like today, succulents of the Victorian period enjoyed widespread popularity, thanks in large part to their reputation as a low-maintenance houseplant. Resistant to dry and dusty air, succulents could withstand the conditions of nineteenth-century homes that were heated by coal fires or gas. Horticulturalist Charles McIntosh noted in 1838 that cacti “require much less labour and attention” than “other exotic plants,” adding that “many of them will exist a long time and without water, without sustaining injury” (171). The Victorian nurseryman Benjamin Samuel Williams was of the same mind, though he described the appeal of succulents a bit more bluntly: “they will bear with impunity a greater amount of neglect than almost any other plants” (38).

Because of their robust nature, succulents offered nineteenth-century poets a compelling vegetal motif for exploring themes of longsuffering, patience, and fortitude. The succulent that particularly embodied these virtues was the aloe. Since they often took decades to flower, aloes, or agaves, earned the colloquial name of “Century Plant.” Embodying a temporality of the singular and the exceptional, aloes could serve as poetic shorthand for events of extreme rarity. “Thou art the aloe of the skies” [30] exclaimed American writer Rosa Vertner Jeffrey in her poem about the 1858 sighting of Donati’s Comet, which only passes the earth once every two-thousand years (81). Poets also refer to this succulent in poems about history. For example, in “On the Celebration of the Three Hundredth Anniversary of the Foundation of Trinity College, Cambridge” (1849), Anna Potts likens the establishment of a storied university college to the long life of an aloe plant:

’Tis said, once only in a hundred years,

The unbending aloe its bright blossom rears,

But, as those years roll silently between.

Far spread its roots, its leaves are thick and green; [55-58]

[…]

Image of that brave plant whose leaves expand,

Whose roots are deepening in the grateful land,

First planted by the royal Tudor’s hand.

Fostered by sunshine, sheltered from the blast.

Three centuries have o’er it scatheless past [61-65]

(82)

By drawing parallels between Trinity College and the steadfast, “unbending” leaves of the aloe, Potts implies that this institution “planted by the royal Tudor’s hand” will continue to flourish for many a century to come.

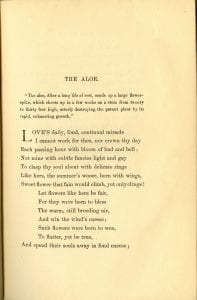

Dora Greenwell, meanwhile, used the lengthy growth cycle of the aloe to extoll human affections founded upon patience, rather than fancy. Instead of the common garden flowers—“subtle fancies light and gay” [4]—that bloom each summer only to “spend their souls away in fond excess” [14], Greenwell’s speaker in “The Aloe” (1869) celebrates “A flower that is not fair, / But wondrous” and “rare” [22-24], which won’t culminate in a fleeting moment of passion (3-4). [Figure 8] Such works show how poets mapped concepts of tenacity and constancy onto these sturdy plants.

Another attribute that made succulents fashionable amongst not only gardeners but also poets was their aesthetic charm. As Williams observed in his handbook on Choice Stove and Greenhouse Ornamental-Leaved Plants (1876, 2nd ed.), “these plants neither lack beauty of form nor diversity of colour, nor singularity or even grotesqueness of appearance” (37). With their sculptural stems and colorful flowers, succulents afforded writers an opportunity to indulge in detailed descriptive passages about vegetal beauty. Take, for instance, Lydia Howard Sigourney’s “To the Cactus Speciosissimus” (c.1841), which opens with the following tribute:

Who hung thy beauty on such rugged stalk,

Thou glorious flower?

Who pour’d the richest hues,

In varying radiance, o’er thine ample brow,

And like a mesh those tissued stamens laid

Upon thy crimson lip? — [1-6]

In a later passage, Sigourney adds that these brilliant red flowers:

“[…] bidd’st the queenly rose with all her buds

Do homage, and the green-house peerage bow

Their rainbow coronets.” [11-13]

(34)

Similar paeans to the grace and grandeur of cactus blossoms appear in poems by Lady Flora Hastings and Mrs. Graham Campbell.

However, as Kent notes in Flora Domestica, the beauty of flowering cacti was often “short-lived,” for the most striking blooms lasted only a “very short duration” (84). Many nineteenth-century poets singled out the night-blooming cereus as both the most beautiful and the most transient of such blossoms. As its name suggests, the night-blooming cereus—a catchall term for several cactus varieties—produces its large, fragrant, snowy blossoms only one night per year. In her language of flowers handbook, Flora’s Lexicon (1858), Catherine Waterman calls the night-blooming cereus “one of our most splendid hothouse plants.” Its flower, she adds, is not just “remarkable” because of it is great size and luminous petals, but also because of “the rapidity with which it decays” (150). Julia Emily Gordon similarly speaks of “transient glee” and “evanescence” (59) when describing a cereus blossom in her poem “The Carnival of Night” (1880), while Eliza Lee Cabot Follen compares the “transient lustre” of this flower to the fading of life’s “sweetest pleasures” and “brightest blessings” (107).

As these poems show, succulents possess an appealing paradoxical complexity that can simultaneously epitomize ephemerality and endurance. Both the aloe and the cereus weather long seasons of growth before they start to bloom, thereby concentrating a wide spectrum of emotional significance into a single plant. The current popularity of succulents suggests that these plants are here to stay, and there remains plenty of research to be done on their cultivation history. I am deeply grateful to the staff of the Armstrong Browning Library for supporting my research on this project and for sharing these collections with me.

Works Cited

Coolbrith, Ina. Songs from the Golden Gate. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1895.

Follen, Eliza Lee Cabot. Poems by Mrs. Follen. Boston: William Crosby & Company, 1839.

Forman, Emily Shaw. Wild-Flower Sonnets. Boston: Joseph Knight Company, 1895.

Gordon, Julia Emily. Songs and Etchings in Shade and Sunshine. New York: Scribner and Welford, 1880.

Greenwell, Dora. Carmina Crucis. London: Bell and Daldy, 1869.

Jeffrey, Rosa Vertner. The Crimson Hand, and Other Poems. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1881.

Kent, Elizabeth. Flora Domestica, or the Portable Flower-Garden; with Directions for the Treatment of Plants in Pots. London: Taylor and Hessey, 1823.

Loudon, Jane. Practical Instruction in Gardening for Ladies. Second. London: John Murray, 1841.

Maling, E.A. In-Door Plants, and How to Grow Them for the Drawing-Room, Balcony, and Greenhouse. London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1862.

McIntosh, Charles. The Greenhouse, Hot House, and Stove. London: William S. Orr and Co., 1838.

Potts, Anna H. Sketches of Character and Other Pieces in Verse. London: John W. Parker, 1849.

Sigourney, Lydia Howard. Selected Poems. Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1843.

Stynen, Andreas. “‘Une Mode Charmante’: Nineteenth-Century Indoor Gardening Between Nature and Artifice.” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 29, no. 3 (2009): 217–34.

Ward, Nathaniel Bagshaw. On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases. London: John Van Voorst, 1842.

Waterman, Catharine H. Flora’s Lexicon: An Interpretation of the Language and Sentiment of Flowers. Boston: Phillips, Sampson, and Company, 1858.

Williams, Benjamin Samuel. Choice Stove and Greenhouse Ornamental-Leaved Plants. 2nd ed. London: Published by the Author, 1876.