By Laura McNeal

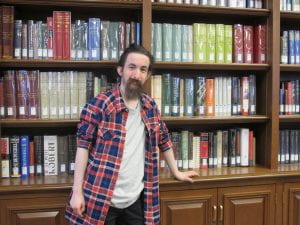

Laura McNeal in the Belew Scholars’ Room, Armstrong Browning Library

The hardest part about bringing Victorians to a modern reader is their reverence. They insist that whatever has been done wrong will be more easily endured or rectified if they never explicitly describe it. In our time, we have the opposite approach: talk talk talk about it, show show show it all, every terrible thing, every violation, every outrage, every shame. All our contemporary discourse–our movies, novels, poems, newspaper articles, and songs—aim to comprehend and heal by having no secrets and almost no taboos. Victorians, however, were very good at keeping secrets and very serious about taboos. They were bound by social and religious constraints that urged reverence for certain ideals, including monogamy, chastity, and dutifulness. We seem (collectively, in the aggregate) to want to tell the truth, whatever it is. They (collectively) wanted to protect a rigid, powerfully idealistic vision of human life.

I came to the Armstrong Browning Library determined, as I suppose most scholars are, to pierce silences, peer into cracks, make new comparisons, illuminate dark spaces, and tell a fresh and somehow edifying truth. I’m not a scholar, though. I write fiction. What I want to find when I read Victorian letters, diaries, reminiscences, articles, and footnotes—especially footnotes, which often lead me to obscure diaries–is an encounter that could be dramatized in a scene. To write that scene I must invent what we can never, ever know: what these actual, once-living people really said to each other at the time and what they thought but couldn’t say because they didn’t want to hurt someone’s feelings or be ostracized by others, or they simply, reflexively thought it best to suppress it. What I have been doing for six years now as I read and write about the Barretts and Brownings is at once a huge violation of their privacy and a rescue attempt. Look at them, I want to say to the world. Look at them, at these earnest, reverent, suffering, fallible, astonishing people who built the ladder and the scaffold and the foundation on which we all stand. What did they do, what did they wish, what did they accomplish, and how did they manage?

Thanks to the continuous efforts of readers and scholars all over the world, and especially, in this area of study, because of the lifelong dedication of Dr. A.J. Armstrong and Philip Kelley, the Armstrong Browning Library offers, in book form and in a vast, searchable database, not only what the poets Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote and the millions (or billions) of pages that have been written about what they wrote, but also what their relatives and friends and important or unimportant acquaintances reported in their diaries and letters, the locks of hair they labeled and saved, the brooches they wore, the paintings they painted, and the inkwells they stared at while the ink dried on the tips of their upheld pens. The volume of material here is staggering and inspiring and accessible, and it’s housed in the most reverent building imaginable. I approached the library on foot every day like a person who knows she has only so long at the buffet. I had been given four generous weeks, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.: all you can eat. After those four weeks, at 5 p.m. exactly, the door to the buffet would be closed to me, and home I would have to go. It was heaven, and I ate everything in sight. I was insatiable. I asked for things and they were brought. I looked up “darling” in the database. I looked up “Domett” and “Bracken” and “Henriette Corkran” and “Mary Gladstone” and “Joseph Milsand” and “Mr. G.D. Giles.” Up floated the letters, the vanished hours, the twilights and fogs. I looked through the magnifying glass, squinted into dark cases. Always at my back was the swiftly approaching end: I would have to go home, and I would have to lay out for myself the million tiny pieces of the Mystery. And I would have to dare to make the dead speak.

Historical fiction is a paradox. I need dates, I need addresses, I need descriptions of drawing rooms and suppers. I have itineraries, I have descriptions of sunsets and rains and walks and feelings and opinions. But I will be using those fragments to conjure the rest. When and where did it happen? certain Norse folk tales end. When and where did it not happen? Those words became a koan in my head while I typed my notes at the Library Buffet. I wrote down every date, every name, every city, every source, and I put it in a file, in a notebook, in a photograph, in a timeline, knowing that while I claim to revere the past I am strip-mining it, running rapaciously through its ruins in search of my materials.

Is this wrong? I comfort myself by remembering that this is what Robert Browning did nearly every day of his life: Sordello is historical fiction. So is Paracelsus. So is The Ring and the Book. Robert Browning burned piles and piles of letters we wish we had, he dreaded the rapacity of biographers, and yet he craved an audience, adored reading his poems to people and longed, as we all do, for immortality, which is what he will have only if people keep writing intrusive stories and essays and dissertations about him. The best I can do is sift my sources carefully. I read and look and read and look and read and look again, taking each reported comment and observation and weighing it for bias. How truthful did other people in the Brownings’ circle think this person was? What motives did the writer have in recording what he or she said? Was there competition of any kind, or a sense of duty and reverence, between the writer and the subject? Were there any past hurts or sleights? If a claim about someone has a whiff of scandal, is there any corroboration? By whom?

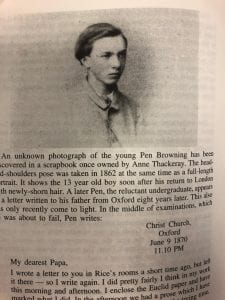

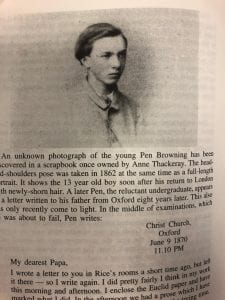

Picture of Pen Browning, age 13, in Browning Society Notes, vol. 22, December 1994. ABL Periodicals

Which brings me to Pen. My month at the buffet was proposed and accepted as a deep and wide consideration of Robert and Elizabeth’s only son, Pen-Penini-Wiedeman, also known as Robert Barrett Browning, who “died without issue” and without (and this determined what people were willing to say about him while he was alive and after he was dead) the glorious, sanctifying esteem enjoyed by his parents. He was not revered as they were for many reasons. One is that he outlived the Victorian age: until 1912. Another is that he didn’t have a glorious love affair and marriage; he had a tepid, dispassionate, unhappy one. He was the target of all the malice and scorn that people tend to feel in our time about the children of celebrities, who having been given money and access to the houses of the rich and powerful are expected to deserve it. Are they as good-looking, original, smart, humble, hard-working, and brilliant as we expect? Does Genius + Genius = Genius? No? Why not? Two poets with bizarrely high levels of self-motivation and linguistic facility who were also loving and faithful and true had a boy they dressed like a girl, or rather, in his mother’s mind, like a “child of poetry,” and for twelve years they raised him in Italy and then, right at the exact moment when he was changing from a boy to a man, his mother died, and while he was adjusting to being a boy who had a living mother to a boy whose mother was dead, he also had to change from being Italian to being English, and from not being in school at all to being in school the way upper-class English boys were in school. What was that like for him? For his father? And is there a way to tell that story without unfairly filling in the blanks where gracious Victorian propriety intersected with vicious Victorian gossip?

During my month at the buffet, I circled around and around these questions, around Pen and his father, his father and Pen, through their departure from Florence to Pen’s failure at Oxford to Pen’s artistic education to Pen’s engagement to a girl Robert told him not to marry to Pen’s marriage to a woman who seemed to love only Pen’s borrowed fame to Robert’s death in Venice to Pen’s death in a messy Florentine villa to the long, long aftermath, which has no terminal point. And every day, four times a day, I took the stairs.

In the stairwell of the Armstrong Browning Library, there are several paintings by Pen, one large and one enormous, and their placement seemed both fitting and sad. “The Abbé with his Books” and “Delivery to the Secular Arm” hang in the stairwell of a shrine built to the memory of his parents, not in the Louvre, not in the National Gallery, not in the Smithsonian, but at least they hang somewhere. They were not destroyed, as some of his paintings were. They are not in a secondhand store in Palm Springs or rolled up in the basement of a small state museum. As I clomped up the linoleum steps, I couldn’t take my eyes away from “The Abbé with his Books” or “Delivery to the Secular Arm.” I wondered, mostly, what makes a good painting great and a great painting famous. I imagined Pen standing in his atelier with a paintbrush, dabbing a little more paint on the edge of a fold of cloth, highlighting the perfect white edge on the collar of the farthest monk to the left, which struck me as supremely beautiful. It takes so long to paint anything. The years of learning how to sketch, how to apply paint, the thousand decisions about what to put in and what to leave out, of who should model for the face of the girl, the face of the inquisitor, the soldiers, the monks, and what expressions they should have on their faces, what their shoes looked like, what pattern to make on the rug. Whose hands modeled for those hands? Did they ever see it, and what did they say? Was there anything Pen might have done to lift the painting beyond its present place in the world, which is a good and noble place, but not the best place, if you’re the artist.

Robert Barrett Browning’s Delivery to the Secular Arm. Armstrong Browning Library. Photo by Laura McNeal.

For me, though, the placement was ideal. It was instructive to see the Abbé and the heretic four times a day, twenty times a week, eighty times in all, each morning or afternoon having expanded my knowledge of their creation by reading different, sometimes contradictory gossip about Pen’s friends, his father’s friends, the patroness who first bought “Delivery to the Secular Arm,” the reviews his paintings received, the troubles Pen had with his eyes and his hands, the remedies his father recommended, and the way it petered out, his artistic ambition.

By my last trip down the stairs, looking at the white light on the monk’s collar–at that perfect illumination of a man’s un-famous, un-hallowed life as an artist–I felt both invigorated and afraid. The library had done its part, answering every question I asked it. Now it was, terrifyingly, my turn. How could I possibly fit all of it in–the disappointment, hope, bitterness, desire, and rage–while maintaining the veil that keeps Victorians Victorian?

Close up of the monk’s collar in Robert Barrett Browning’s Delivery to the Secular Arm. Armstrong Browning Library. Photo by Laura McNeal.

One of the last things I copied out word for word into my phone, so I could read it anywhere I go, was this bit of a letter from Henry James to a novelist named Violet Paget (her pen name was Vernon Lee) on May 16, 1885, with his thoughts on her novel, Miss Brown.

…It will probably already have been repeated to you to satiety that you take the aesthetic business too seriously, too tragically, and above all with too great an implication of sexual motives. There is a certain want of perspective and proportion. You are really too savage with your painters and poets and dilletanti; life is less criminal, less obnoxious, less objectionable, less crude, more bon infant, more mixed and casual, and even in its most offensive manifestations, more pardonable, than the unholy circle with which you have surrounded your heroine. And then you have impregnated all those people too much with the sexual, the basely erotic preoccupation: your hand had been violent, the touch of life is lighter.

…You have proposed to yourself too little to make a firm, compact work—and you have been too much in a moral passion! That has put certain exaggerations, overstatements, grossissements, insistences wanting in tact, into your head. Cool first—write afterwards. Morality is hot—but art is icy!

I haven’t read Miss Brown, not yet, but James seems to be answering my own question about the preoccupations of our time. Life is less criminal, less obnoxious, less crude, more mixed and casual, than we often depict it as being, both then and now. As soon as I can sort all these painters and poets and dilletanti I will set to work, being not too savage, I hope, and trying for a firm, compact work. Meanwhile, if you are in need of inspiration, go to Waco, Texas, on a weekday between 9 and 5. Go to the meditation room in the Armstrong Browning Library to see what immortality looks like. For a glimpse of mortality, though, which can be just as moving, take the stairs.

On November 17th, The Armstrong Browning Library had the distinct privilege to learn about a fascinating historical figure in the lecture “Harriet Martineau, Spirit of the Victorian Age” from the distinguished Dr. Deborah A. Logan, this year’s speaker for Benefactors Day. Benefactors Day is a yearly celebration of our wonderful community of supporters that ensures the future of the Armstrong Browning Library’s scholarship and programming work. A professor emerita of Victorian Literature at Western Kentucky University, Dr. Logan captured this year’s audience by shedding light on the life and works of the Victorian author, economist, journalist, sociologist, and Browning correspondent, Harriet Martineau.

On November 17th, The Armstrong Browning Library had the distinct privilege to learn about a fascinating historical figure in the lecture “Harriet Martineau, Spirit of the Victorian Age” from the distinguished Dr. Deborah A. Logan, this year’s speaker for Benefactors Day. Benefactors Day is a yearly celebration of our wonderful community of supporters that ensures the future of the Armstrong Browning Library’s scholarship and programming work. A professor emerita of Victorian Literature at Western Kentucky University, Dr. Logan captured this year’s audience by shedding light on the life and works of the Victorian author, economist, journalist, sociologist, and Browning correspondent, Harriet Martineau.

Anna Clark

Anna Clark