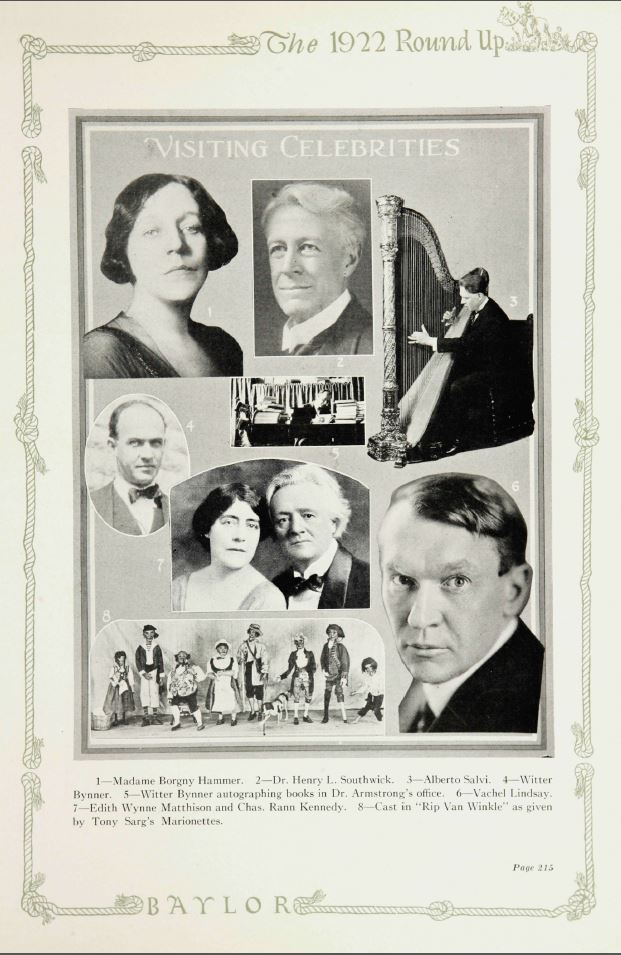

“Armstrong’s Stars” is a collaboration between the Armstrong Browning Library and Baylor’s Texas Collection. Once a month we feature a story about a celebrity who Dr. A.J. Armstrong brought to Baylor. These stories highlight an interesting part of Baylor’s history and include collection materials housed in both the Armstrong Browning Library and the Texas Collection.

This month’s story was contributed by Amanda Mylin, graduate assistant, The Texas Collection.

When renowned African-American singer Marian Anderson was not permitted to sing in the Daughters of the American Revolution’s Constitution Hall in Washington, D. C. in March 1939, the nation reacted (in large part) with astonishment. Anderson is quoted in an article published in the Baylor Lariat saying, “It shocks me beyond words that after having appeared in the capitols of most of the countries of the world, I am not wanted in the capitol of my own country” (“D.A.R. and Americanism,” 2).

Eleanor Roosevelt’s response was the most notable: the First Lady protested the move by resigning from the DAR, and encouraging a concert at an even more prominent venue. Anderson performed a free open-air concert at the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday, April 9, encouraged and arranged by the First Lady, Anderson’s manager, Walter White of the NAACP, and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes.

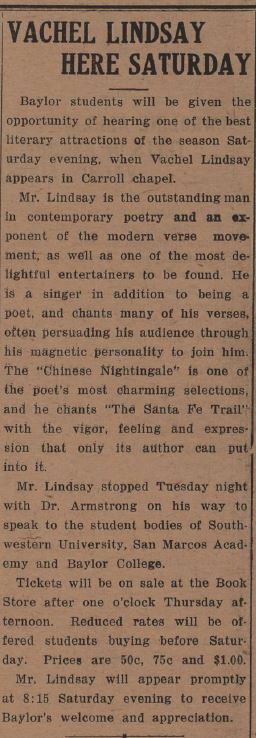

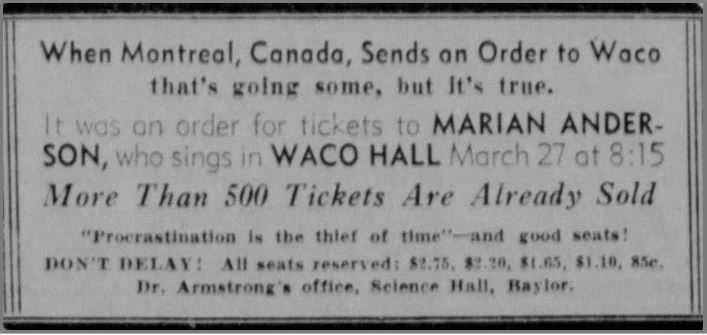

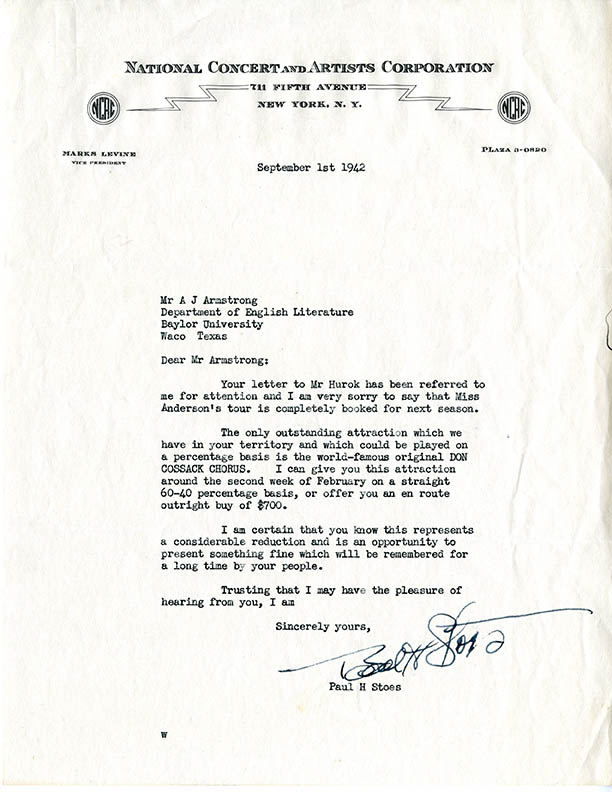

In the midst of this drama, Anderson came to Baylor. Two weeks before her famed Easter concert, Anderson performed at Baylor University’s Waco Hall at the behest of Dr. A. J. Armstrong and Sigma Tau Delta. She was the first African-American soloist to grace the Hall. Her March 27 performance included an array of spirituals and compositions by Handel, Schubert, and Carissimi. The Baylor Lariat for March 3 stated that Sigma Tau Delta had taken the “liberal side of the week’s race question” by selecting Marian Anderson to perform (“Negro Singer Will Follow First Lady,” 4). The same article also noted that Mrs. Roosevelt would speak in Waco Hall on March 13, two weeks before the concert. A nationwide commotion had found its way to Baylor’s campus in a small capacity.

Anderson’s performance was well-received by the Waco audience even though it was primarily formed of a distinct “cross-section of the community’s white citizenship.” The Waco News-Tribune for the next day stated that this turn-out “was pretty much proof that the DAR of Washington, D. C., acted in silly fashion to say the least” (“Marian Anderson is Well Received by Waco Audience”). Furthermore, this article mentioned that Anderson’s well-attended performance was an instance of a slow but steady “solution of a leading American problem.”

Interestingly enough, even Waco Hall remained segregated for Anderson’s concert, with a special portion of the balcony reserved for African-Americans. Eventually, Anderson would insist upon what she called “vertical” seating for her concerts, with available seats throughout the auditorium reserved for African-Americans, and by 1950, she refused to sing for segregated audiences. Yet in the wake of the Constitution Hall incident, Anderson was pleased to perform at Baylor by invitation of Dr. Armstrong.

Although Anderson was in a hurry and allegedly declined to discuss her recent deterrence by the DAR and the First Lady’s defense of her attempt to perform, she did offer a small informal interview to the Baylor Lariat. She had never been to Waco and commented on the beauty of driving through the Texas countryside from San Antonio. Her enthusiasm and unstoppable energy seemed to bubble over as she explained, “I think America offers vast unlimited opportunities for youthful singers who have the seriousness and determination to become great artists no matter what their race of color” (“Eleanor Roosevelt Versus D.A.R. Feud is Closed; Field Unlimited, Says Anderson,” 1).

Sources:

“Negro Singer Will Follow First Lady,” Baylor Lariat, March 3, 1939.

“D.A.R. and Americanism,” Baylor Lariat, March 23, 1939.

“Eleanor Roosevelt Versus D.A.R. Feud is Closed; Field Unlimited, Says Anderson,” Baylor Lariat, March 28, 1939.

“Marian Anderson to Sing in Waco Hall: Famous Conductor Says Negro Artist is Best Living in This Day,” Baylor Lariat, March 22, 1939.

“Marian Anderson is Well Received by Waco Audience,” The Waco News-Tribune, March 28, 1939, Newspapers.com (accessed April 9, 2015).

Learn more about Armstrong’s Stars in previous posts.

Postcards dated 1908 and undated

Postcards dated 1908 and undated