One of my fellow librarians at The Texas Collection tells me that if I get through a day without learning something new, I’m not doing my job. Well, yesterday I learned about a larger-than-life Texas cowboy: John “Catch-Em Alive Jack” Abernathy.

I was cataloging some items from the Adams-Blakley Collection–a fabulous group of books assembled by Ramon F. Adams, the Western bibliographer, lexicographer, and author, for William A. Blakley, a U.S. Senator from Texas. In that collection I came upon A Son of the Frontier by John Abernathy, and I saw a picture of Abernathy, a wolf, and Theodore Roosevelt. I had to find out more, and here’s the story.

Jack Abernathy was born in 1876, in Bosque County, Texas not too far from Waco. He worked as a cowboy, a farmer, and a piano and organ salesman, but became famous for catching over a thousand wolves alive with his bare hands. It seems that Abernathy once accidentally discovered that by thrusting his hand into an attacking wolf’s mouth and holding the lower jaw to keep it from closing, he could capture the animal without losing the hand. Teddy Roosevelt heard about his unique skill, and arranged to join Abernathy in Oklahoma for six days of wolf-coursing. They say that the president wanted to try Abernathy’s technique himself, but the Secret Service talked him out of it. A wise decision, for in his book Abernathy notes,

“Men whom I have tried to teach the art of wolf catching have failed to accomplish the feat. I have tried to teach a large number, but when the savage animal would clamp down on the hand, the student would become frightened and quit. Consequently, the wolf would ruin the hand.” (p.20)

Roosevelt was quite taken with “Catch “˜Em Alive Jack” and appointed him the youngest U.S. Marshal in history. As U.S. Marshal for Oklahoma, Abernathy “captured hundreds of outlaws single-handed and alone, and placed seven hundred and eighty-two men in the penitentiary.” (p.1)

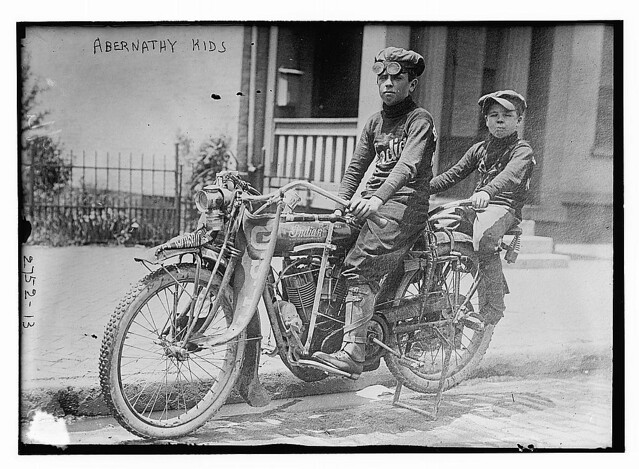

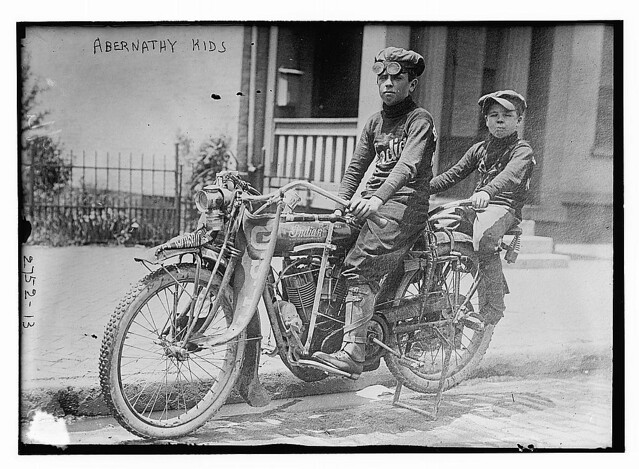

One final note: Abernathy’s sons Louie (Bud) and Temple became famous in their own right. In 1910, at the age of 10 and 6, they rode alone on horseback from their home in Frederick, Oklahoma to New York City to greet President Roosevelt upon his return from a trip to Europe and Africa. Several years later they set out for further adventures on an Indian motorcycle. Temple tells about their journeys in Bud and Me: the True Adventures of the Abernathy Boys.

Jack Abernathy’s story is only one of the many great titles that make up the Adams-Blakley Collection. There are outlaws and lawmen, pioneers and entrepreneurs. Someday, we’ll have to sit a spell and I’ll tell you more.