by Kristin Huggins, Consultant

In music, there is no such thing as an insignificant note. A musician must carefully examine each musical notation and interpret it through the lens of style, story, and audience. Similarly, writing demands that we, the writer, drill down through every clause, every synonym, every semi-colon to determine how our writing will be interpreted by our readership. However, when working through larger projects (i.e., a master’s thesis or doctoral dissertation) these tiny details become blurred in the face of larger, macro-level writing issues. Where does this leave the proofreading process? Cue the green and gold smoke signal for help!

The seven tips below are a culmination of both personal habits and strategies shared by colleagues and professors over the years. While collectively these tips are not foolproof, they serve as a great way to start the proofreading process!

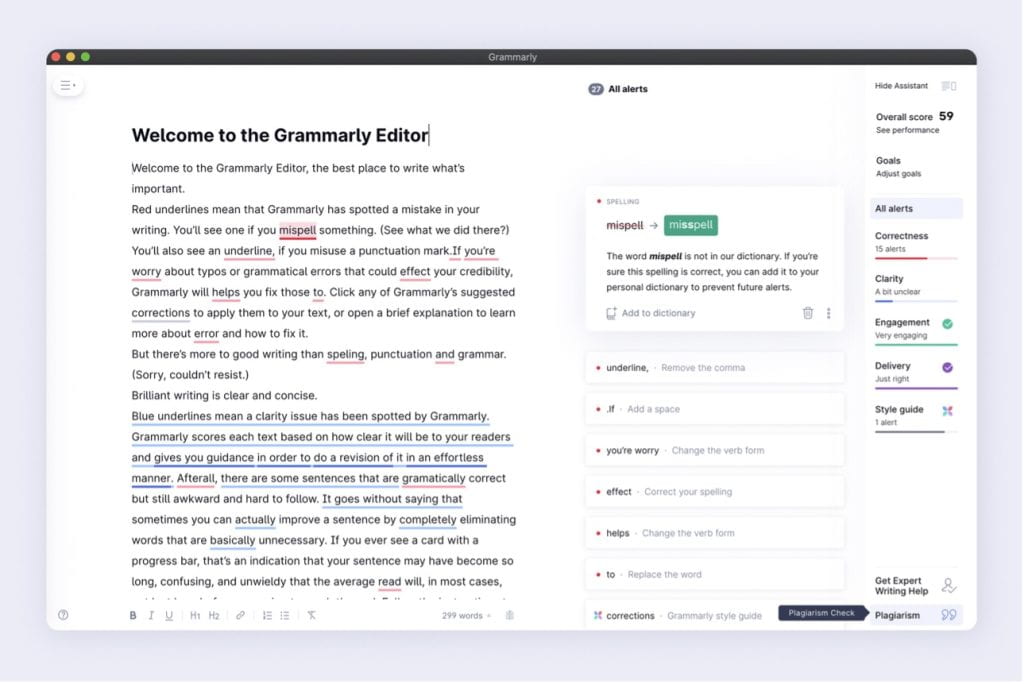

- Download Grammarly to Microsoft Word. I cannot stress enough the value of this program. Grammarly is AMAZING. Fun Fact: Word’s spell-check runs an entirely different algorithm than Grammarly when reviewing papers. This means that with the power of both, you’re more likely to catch those pesky issues hiding in the crevices of your paper. Grammarly offers both a free version and a paid premium version. I use the free version, mainly because the thought of paying for yet another subscription makes my stomach turn. But many colleagues swear by the premium. Try both for yourself!

- Read your work out loud. Yes, academic writing is not the same as colloquial speech. I’m well aware. However, when speaking through your paper, you’ll find moments where you pause subconsciously to consider a phrase or punctuation that doesn’t feel “quite right”. Follow that gut reaction. Question it. Determine whether it has merit and write from there. This trick is also helpful in addressing larger concerns such as flow or topic congruency.

- Become best friends with your Search Bar. If you open your Sidebar in Word, you will be able to Search specific phrases, letters, punctuation, or even extra spaces in your paper to see where and how often they occur. This tool has been my saving grace in finding places where I accidentally inserted two spaces after a period rather than one. I also use this feature to discover my “Word of the Week” (i.e., the adverb or adjective my brain has decided to play on loop during my drafting sessions). Searching for these repetitive words allows me the opportunity to consider whether they are truly appropriate and whether a synonym would be of better use.

- Do not attempt to tackle your entire work at once – especially if it is multiple chapters. This piece of advice is also applicable for writing consultations. You’re much more likely to be effective in your writing goal if you break it down into digestible chunks. The prospect of proofreading a 200-page dissertation within one sitting is inconceivable. I like to approach difficult chapters during my most productive hours of the day when I know my brain will be firing on (nearly) all cylinders.

- Proofread content and style separately. Many find it effective to proofread papers for academic style errors (i.e., APA, MLA, Turabian, etc.) without addressing in-text content. Some have this gift. I wish I was so blessed. Alas, I cannot rub my belly and pat my head at the same time, therefore I will assume that proofreading multiple levels of style, content, and grammar will only result in tears.

- Try tactile proofreading. Staring at screens for hours on end has an odd effect on how the brain processes language, at least in my personal experience. Some of my best revision work has come from printing a chapter and setting to it with a traditional red pen (or green, if you prefer soothing, positive colors). Feeling the crispness of individual pages while setting your thoughts to paper with actual ink is a very different experience than scrolling through Word document pages and adding strikethroughs. Try it once and see what happens.

- Use a Proofreading Checklist to help guide you. Even the seasoned scholar falls into the trap of trying to tackle all proofreading tasks at once. Experience may make the writer, but the writing process remains a fluid embodiment of evolving critical thought and creative output. This means that proofreading can never be worked into muscle memory, but must constantly be attacked at all angles methodically and carefully. The use of a checklist can be liberating, providing the writer with a strategic plan of attack. A sample proofreading checklist can be found here, provided by Southeastern University’s Writing Center.

We hope that you continue to hone your skills as a writer, editor, and proofreader! If you’re new to the proofreading game, these seven tips should jumpstart your proofreading process. If you’re a veteran proofreader and you have additional tips or tricks to the proofreading process, please share below!