“You invite me to break the first law of storytelling, Miss Rose,” said the doctor, lifting a finger at her. “Every man is bound to leave a story better than he found it.”

Mrs. Humphry Ward. Robert Elsmere.

London: Smith, Elder, & Co., 1888, p. 63.

Mary Augusta Ward was an English novelist, journalist, philanthropist, and anti-suffrage leader who wrote under the name of Mrs. Humphry Ward. During her lifetime, she wrote three plays, nine non-fiction works, and twenty-five novels. Many of her novels depict contemporary theological and moral debates. Her most famous novel, Robert Elsmere, focuses on religious issues.

Mary Augusta Ward. Robert Elsmere. London: Smith, Elder, & Co., 1888.

This novel was Ward’s most famed work due to the controversial “deconversion” of its main character from Anglican Christianity to “a liberal, antidogmatic theology.” The story was inspired in part by her own experience with the Victorian religious crisis and by the religious indecision of her father, Thomas Arnold. W. E. Gladstone, a prominent English politician and a four–time Prime Minister, wrote a response to Ward’s work, noting that Mrs. Ward’s aim was to “expel the preternatural element from Christianity, to destroy its dogmatic structure, yet to keep intact the moral and spiritual results.”

Her social and political novels portray her conservative beliefs, concerning both liberalism and feminism. According to Judith Wilt, Professor of English Emerita at Boston College, Ward was concerned with “…the ideal of domesticity crossed by currents of personal ambition and clear-eyed impatience with the limitations of a woman’s life evident in the ideology of separate spheres.” Wilt continues stating, “As a young matron Ward was ‘all afire’ for women’s education…and she continued to see as part of the inherited ‘domestic’ territory to be legislated and run by women as well as men not only all branches of education but also all health and social service professions, and even “local government,” including school boards, municipal boards, and other offices and activities that had become gender-neutrally votable and electable by the 1880’s. For her, ‘domesticity’ included virtually all the national business. When in her anti-suffrage campaigns she drew the line at giving women the vote for Parliament members it was partly a not-unhealthy impatience with what we might now call the fetishization of that object, and partly a curtsy before Empire, a hesitation before the international ministries for finance, heavy industry, and war.” (Judith Wilt, Behind Her Times: Transition England In The Novels Of Mary Arnold Ward, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, p. 14.)

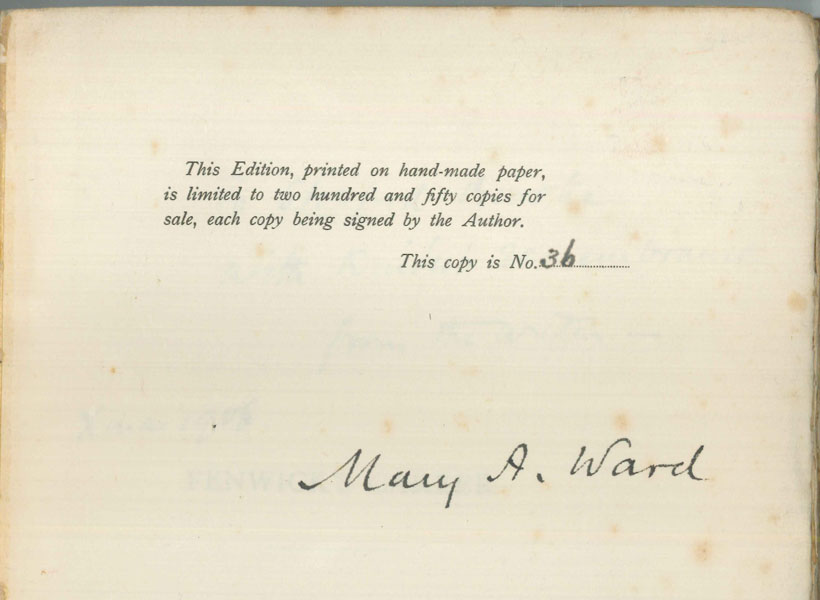

The Armstrong Browning Library owns forty-one volumes authored by Mary Ward, including Fenwick’s Career, which was published in London by Smith, Elder, & Co. in 1906. This edition was printed on hand-made paper. Only two hundred and fifty copies were for sale with each copy autographed by the author. The ABL’s copy is No. 36, and is signed “Mary A. Ward” on the first front leaf. The book tells the story about “a boorish, conceited, masterful young countryman…[whose] supreme longing is ‘to make a name for himself and to leave his mark on English art.”

Autograph by the author, Mary Augusta Ward, on the first front leaf of Fenwick’s Career, London: Smith, Elder, & Co., 1906.

Fannie Browning, wife of Robert Barrett Browning, owned a copy of Amiel’s Journal (1896), which was translated by Mrs. Ward; Robert Barrett Browning, Robert and Elizabeth’s son, owned a copy of The Marriage of William Ashe (1905), with the author’s inscription. Although the Armstrong Browning Library does not own this book, it does have a copy of the same edition once owned by Robert Barrett Browning.

Tiffany Huynh

Maegan Rocio

Michael Moreno

Melinda Creech

A letter at the Armstrong Browning Library from Mary Augusta Ward has recently come to light—

61. Russell Sq.

April 19. /88

My dear Mr. [Cabbe]

Thank you very much for your kind offer of the farm which I am sure would be delightful in May. But our children are now at borough & must come ^home^ again & begin work by the 4th of May. They will then have had a month in the country. So I am

[Page 2]

afraid we must decline your tempting suggestion but many thanks for it all the same.

Yes. This has been a terrible fortnight. I am going down to Borough as soon as I can for some rest. One feels shattered by it all.

Very sincerely yours

Mary A. Ward