Nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee!

E’en though it be a cross that raiseth me;

Still all my song shall be nearer, my God, to Thee,

Nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee!Though like the wanderer, the sun gone down,

Darkness be over me, my rest a stone;

Yet in my dreams I’d be nearer, my God, to Thee,

Nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee!There let the way appear steps unto heav’n;

All that Thou sendest me in mercy giv’n;

Angels to beckon me nearer, my God, to Thee,

Nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee!Then with my waking thoughts bright with Thy praise,

Out of my stony griefs Bethel I’ll raise;

So by my woes to be nearer, my God, to Thee,

Nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee!Or if on joyful wing, cleaving the sky,

Sun, moon, and stars forgot, upwards I fly,

Still all my song shall be, nearer, my God, to Thee,

Nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee!Sarah Flower Adams

“Nearer My God to Thee”

Hymns and Anthems, compiled by William Johnson Fox

London: Charles Fox (1841)

Virginia Blain, professor in English at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, editor of the Feminist Companion to Literature, and editor of the new Dictionary of National Biography, suggested to me that Sarah Flower Adams was best known for her composition of “Nearer My God to Thee.” The song became famous for allegedly being played by the musicians of the Titanic as it sank. The song has also traditionally been played at the funerals of American presidents. Less well known about the hymn, probably because all the verses are seldom sung, is the fact that the song is based on the story of Jacob’s dream in Genesis 28: 10-28. In the story Jacob, traveling to his homeland to look for a wife, retires for the evening with a stone for a pillow and dreams of angels ascending and descending a ladder to heaven. The Lord stood at the top pronouncing a blessing on him and his descendants and promised to be with him always.

Sarah Flower Adams was born in Essex, England, the daughter of Benjamin Flower, a radical journalist and political writer. Sarah and her sister Eliza, a composer, were close friends of Robert Browning and corresponded with him frequently. Eliza is said to have been the inspiration for Robert Browning’s Pauline (1833). After her father’s death, Sarah contracted tuberculosis. Recuperating on the Isle of Wight, she composed her first long poem, “The Royal Progress.” Sarah wrote poems on social and political subjects, a religious catechism for children, dramatic poems, and even attempted a career as an actress. In 1834 she married William Adams, a civil engineer. Her greatest achievements, however, were literary rather than dramatic. Adams’ longest work, Vivia Perpetua: A Dramatic Poem (1841), recounts the third century martyrdom of Vivia Perpetua. Of course, Adams is best remembered for her hymns. Blain suggests those “simple expressions of devotional feeling at once pure and passionate, can hardly be surpassed.”

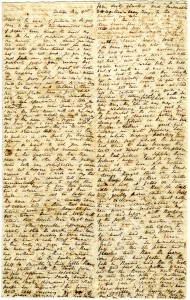

The Armstrong Browning Library owns a copy of Vivia Perpetua: A Dramatic Poem (1841), inscribed by the author, “Celina Flower. With love from The Author – 1841.” The ABL also owns a very important letter written by Sarah Flower Adams to William Johnson Fox. After the death of her father, Sarah lived with the Fox family and contributed to the Monthly Repository, a magazine Fox was managing at the time. In this letter, written to Fox on May 31, 1827, Sarah Flower begins by bemoaning the degradation of the “immense hot house” of London and reminiscing about her recent glorious stay in the country. She then introduces Fox to the juvenile poetry of “the boy” Robert Browning, quoting two of his poems, “The First Born of Egypt” and “The Dance of Death.” This letter is significant because Browning eventually destroyed the manuscripts of his entire first volume of poems, Incondita, and these two poems transcribed by Sarah Flower are all that remain. The last two pages of the letter contain the transcription of Robert Browning’s poems.

May 31, 1827

Sarah Flower to William Johnson Fox

courtesy of the Armstrong Browning Library

Notes & Queries:

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography describes Eliza Flower as “the greatest female composer the country had yet seen.” However, I have only been able to find one piece of her written music, “Now Pray We,” in The Bristol Tune Book (1891). Does anyone know where to find her music?

Very interesting. Is it true that at one time while still venerating Shelley, Robert Browning convinced her of atheism/agnosticism — for one night?

I have found a transciption of a letter from Sarah Flower to Rev. Fox from Harlow, November 23, 1827, that recounts the struggle of faith of a twenty-two year old girl in Daniel Moncure’s Centenary History of the South Place Society: Based on Four Discourses Given in the Chapel in May and June, 1893 … Williams and Norgate, 1894, p. 45 f. She mentions there being influenced by Robert Browning. The letter is also recorded in Richard S Kennedy and Donald S. Hair’s The Dramatic Imagination of Robert Browning: A Literary Life. University of Missouri Press, 2007, p. 20.

As Kennedy points out this is the very honest expression of a crisis of faith encountered by a fifteen year old and a twenty-two year old. It is, in fact, refreshing to hear the sensitivity expressed in the letter. Robert and Sarah make their way through their struggle and go on to write great affirmations of Christian faith in their poetry and hymns.