Goblin Market and Other Poems. By Christina Rossetti. With two designs by D. G. Rossetti. London: Printed by Macmillian and Co., Henrietta Street (1862).

(ABLibrary 19thCent PR5237.G6 1862) ABL Women Poets Collection.

Beyond the Threshold: Death, Nature, and Religious Life in Hopkins’s Response(s) to Rossetti’s “The Convent Threshold”

By Sarah Kaderbek

To highlight once again Gerard Manley Hopkins’s engagement with and love of Christina Rossetti’s poetry is perhaps highly satisfying to fans of both poets but potentially redundant. Thus, in so doing again, we must forefront what the connection contributes to our understanding rather than relying on what it adds to our personal satisfaction as fans and scholars. Following a thread of connection from Rossetti’s 1862 collection Goblin Market and Other Poems through Hopkins’s 1864 letter to Alexander William Mowbray Baillie and diary from the same year reveals the extent to which Hopkins actively engaged with and repurposed Rossetti’s poetry.

The key to this analysis is found, however, first and foremost within Rossetti’s 1862 publication, Goblin Market and Other Poems, an edition of which is housed in the Armstrong-Browning Library at Baylor University in Waco, TX. The publication is relatively simple with a black cover and gilt spine and includes two “designs” by Rossetti’s brother, Dante Gabriel, as the title page advertises. This particular copy contains minimal to no marginal markings, and thus, its most significant archival value is perhaps this condition, which affords us a contemporary reader’s textual experience, particularly as regards the poems’ selection and organization within the collection. Notably, the poems are parsed into two sections, with “Devotional Pieces” separated out from the general poetry.

In addition to this rare book, the other archival materials mentioned in this post are Hopkins’s 20 July–14 August 1864 letter to Alexander William Mowbray Baillie and his 1864 diary. Although these materials were unavailable at the Armstrong-Browning Library, transcriptions of these writings have been printed within Oxford UP’s The Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, volumes 1 and 3 respectively, and are available digitally by subscription as part of the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) database.

Based on these documents and considering Rossetti’s “The Convent Threshold” in its original 1862 publication context as Hopkins would have experienced it, we can examine further connections between their poetry beyond, though building upon, Hopkins’s explicit poetic response to “The Convent Threshold” in his 1864 draft of “A voice from the world.” In this way, Hopkins’s poetic exchange with Rossetti, beginning with “The Convent Threshold,” itself becomes an interpretive threshold into Hopkins’s development of his poetry and meditations upon nature, death, and religious life in a number of his most famous works, including both “Heaven-Haven” and “The Wreck of the Deutschland.”

Within Rossetti’s collection, one of the most narratively striking poems is “The Convent Threshold,” in which Rossetti imagines her (female) speaker at the moment of entrance into religious life. Notably, despite the ostensibly religious theme, Rossetti does not include “The Convent Threshold” amongst the “Devotional Pieces” in this collection, although it serves as the penultimate poem just before that section begin. Metaphorically standing on the convent threshold, Rossetti’s speaker meditates upon why she is taking this step and calls her former lover to repentance, confessing:

My lily feet are soiled with mud, With scarlet mud which tells a tale Of hope that was, of guilt that was, Of love that shall not yet avail (19)[1]

This “scarlet mud” and “guilt” comes from her love for the man to whom the poem is addressed, with whom she “sinned … a pleasant sin” (presumedly sexual and potentially incestual), and thus whom she calls to “repent with me, for I repent” (Rossetti, “Convent,” 119, 122). That he will do so is left unlikely, as she admits, “Your eyes look earthward, mine look up” (Rossetti, “Convent,” 120).

A few years after Rossetti’s collection was published, however, Hopkins drafts a poem which literally responds to the call issued in “The Convent Threshold.” In a letter to his friend and correspondent Alexander William Mowbray Baillie, composed across July and August 1864, Hopkins details his recent poetic endeavors, including a “nearly finished … answer to Miss Rossetti’s Convent Threshold, to be called A voice from the world, or something like that, with which I am at present in the fatal condition of satisfaction” (Hopkins, “July 20,” 64). In his diary from the same year (1864), Hopkins records this draft:

Who says that angels, ^in^ your ear Are heard, that cry “She does repent”, Let charity thus begin at home,- Teach me the paces that you went I can send up an Esau's cry; Tune it to words of good intent. This ice, this lead, this steel, this stone, This heart is warm to you alone; Make it to God. I am not spent So far but I have yet within The penetrative element That shall unglue the crust of sin. Steel may be melted and rock bent. Penance shall clothe me to the bone. Teach me the way: I do will repent. (167)

In “A voice from the world,” then, we see Hopkins’s speaker respond to the call to repentance issued by Rossetti’s speaker in “The Convent Threshold” with a similar vow of penance, although one still troublingly connected to the female speaker. While acknowledging that, currently, his “heart is warm to [her] alone,” he asks her to “teach me the paces that you went” that he might thereby “Make [his heart warm] to God,” signaling his own willingness to penitentially enter religious life, albeit of course within a male community.

That Hopkins responds thusly to Rossetti’s poem is significant both in itself and for the way he does so. On the first level, his direct and literal response establishes the nature and extent of his engagement with Rossetti’s poems, particularly those of this collection (Goblin Market and Other Poems) at this time (1864). On the second, Hopkins’s speaker, like Rossetti’s, emphasizes the need for penance and speaks of penitential suffering as “the paces [she] went” (167). In this view, the cloister is considered synonymous with penance. Rossetti’s speaker describes the vision of eternity and the triumph of the church in Revelation 15:2 as a “sea of glass and fire” (119) and Hopkins’s describes how in following her “paces,” perhaps as a monk or priest, “Penance shall clothe [him] to the bone” like a religious habit (167). In contrast to the to the convent’s religious aspiration, the world and nature are presented only as barriers to the speakers’ requisite conversions. Rossetti’s former lover looks “earthward” toward other young men and women, and his temptations therein are described using nature-rich imagery: “milk-white, wine-flushed amongst the vines …. Blooming as peaches pearled with dew” (Rossetti, “Convent,” 122-23). Conversely though connectedly, Hopkins’s speaker describes himself in unflattering, Natural metaphors, referring to his sinful heart as “This ice, this lead, this steel, this stone” (Hopkins, “Diary,” 167). The beauty- and meaning-flooded nature typical of these poets’ writings is noticeably absent; instead, both poets primarily frame nature as representative of the temptations present within the world and cloistered religious life as a penance necessary to purge them of the world’s influences.

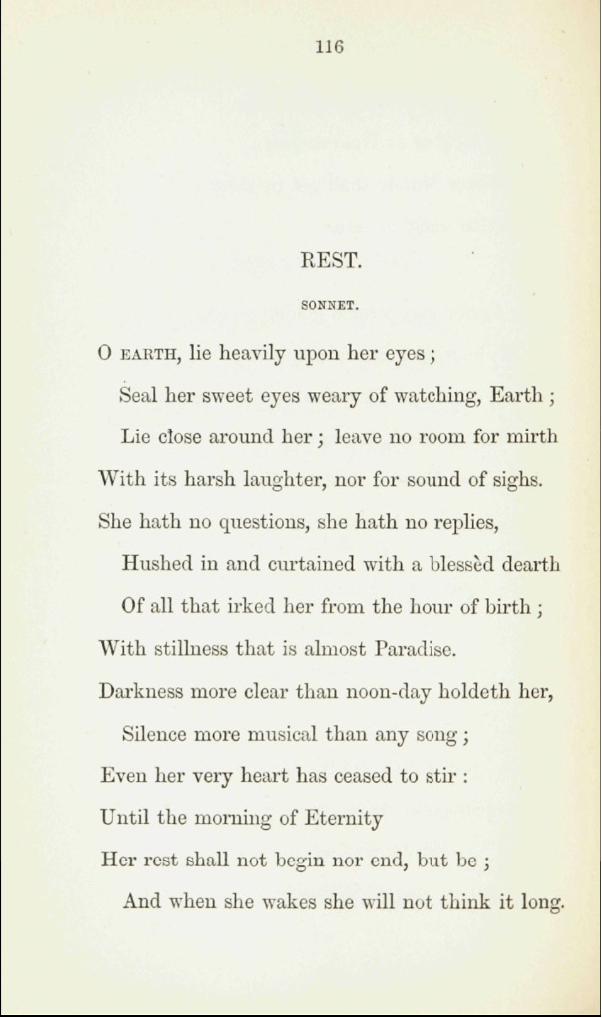

Although it might seem obvious to connect both of these poems directly to Hopkins’s finished poem “Heaven-Haven,” in which he himself adopts the voice of “a nun tak[ing] the veil,” Hopkins’s depiction of the convent as haven has little in common with the primarily suffering, penitential voices of “A voice from the world” and “The Convent Threshold.” Instead, our understanding of “Heaven-Haven” is dependent on recognizing its parallels to and perhaps roots in Rossetti’s “Rest,” a sonnet included in the same 1862 publication as “The Convent Threshold,” placed only a few pages prior within the book. Topically, this may seem counterintuitive in that Rossetti’s “Rest” refers to the rest found in death, and Rossetti’s language is here significantly more positive than in “The Convent Threshold.” Whereas entering the convent was framed as an act of penance in response to and escaping a temptation- and sin-wracked world, death is described in “Rest” as a peaceful entering into nature. The speaker of this poem reflects on her hope that “Earth” will “seal [the dead woman’s] eyes weary of watching” and that in her grave, she will be:

Hushed in and curtained with a blessèd dearth

Of all that irked her from the hour of birth;

With stillness that is almost Paradise.

Darkness more clear than noon-day holdeth her,

Silence more musical than any song; (Rosetti, “Rest,” 116)

Thus, although the woman has lost her sensual and personal experience of nature via her death, she has also entered into a fuller communion with it via her burial.

Although this poem initially seems to have little to do with Hopkins and the previous pair of poems, in Hopkins’s same 1864 diary in which “A voice from the world” appears, he also writes the first draft of “Heaven-Haven,”sans epigraph and bearing its original title of “Rest”—the same as Rossetti’s sonnet. This new pair of poems thus features parallel adjacence as “A voice from the world” and “Threshold” within Hopkins’s diary and Rossetti’s collection and bears identical titles. While these features could be merely coincidence however, the two “Rest”s—Rossetti’s sonnet and Hopkins’s draft of “Heaven-Haven”—also share similar language and themes. Just as Rossetti’s “Rest” presents the Earth as a place of rest to abide within as one waits for the coming Paradise, so does Hopkins’s “Heaven-Haven,” reversing the depiction of religious life presented in “A voice from the world.” Shifting away from an association of religious life as penance and an exit from nature, it instead becomes indicative of exactly what the original title says—rest—and particularly a rest enabled by nature. The convent is compared to a field or harbor sheltered from “sharp and sided hail” “where no storms come”: a sheltering haven much like Rossetti’s description of the grave in “Rest” (3, 6).

Also similar to Rossetti’s poem, the achievement of this shelter in “Heaven-Haven” requires both an entering into and a sacrifice of nature. In death, Rossetti’s subject becomes part of the Earth even as she loses the ability to behold it via her living senses. Although this shift is portrayed as a primarily positive one, it still necessitates a loss. And in Hopkin’s “Heaven-Haven,” as the nun takes the veil, she gains a heaven, a beautiful and peaceful one, but one in which only a “few lilies blow” and the havens are “dumb, / And out of the swing of the sea” (Hopkins, “Heaven-Haven,” 4, 7-8). Considering these connections between Rossetti’s “Rest” and Hopkins’s “Heaven-Haven,” we can see more clearly the tension presented in these poems between the poets’ earlier depictions of religious life and Hopkins’s later reworking of the topic, as well as their conflicted representations of the world and nature. Ultimately, however, these explications perhaps raise more questions than they answer.

Originally drafted in 1864, the final title of “Heaven-Haven” does not appear until an autograph draft dated to 1867 or 1868, although a variety of titles explicitly connecting the poem to its final context appear in manuscripts and copies as early as 1865 (Mackenzie 240). Knowing this, the question becomes whether Hopkins drew this connection between the rest afforded by death and that by the convent in the initial draft or over time? Was “Heaven-Haven” originally about death, like Rossetti’s sonnet, and the connection to religious life only developed later? Or was his “Rest” about entering the convent from the beginning, reworking and re-understanding Rossetti’s depiction of death? Did he, in renaming his “Rest,” seek to distance it from this association with death? To make matters more complicated, in the middle of these title changes came Hopkins’s conversion from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. Did his entrance into a tradition more thoroughly recognizant of positive monastic life effect the change in his approaches between “A voice from the world” and the final version of “Heaven-Haven”? While there are no easy answers to these questions, they merit further reflection, as does Hopkins’s triangulated association between convents, nature, and death which is herein fore-fronted and which appears through Hopkins’s writings, particularly within his magnum opus “The Wreck of the Deutschland.”

Works Cited

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. “20 July–14 August 1864 to Alexander William Mowbray Baillie.” The Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, vol. 1, ed. K. R. R. Thornton and Catherine Phillips, Oxford UP, 2013, pp. 62–65. Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780199533985.book.1

—. “Diary for 1864.” The Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, vol. 3, ed. Lesley Higgins, Oxford UP, 2015, pp. 136–268. Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780199534005.book.1.

—. “Heaven-Haven.” The Major Works, ed. Catharine Phillips, Oxford UP, 2009, pp. 27.

MacKenzie, Norman, editor. The Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, 4th ed, Oxford UP, 1967.

Rossetti, Christina. “The Convent Threshold.” Goblin Market and Other Poems, London, 1862, pp. 119-27. Baylor University Digital Collections, digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/goblin-market-and-other-poems-by-christina-rossetti-with-two-designs-by-d.-g.-rossetti/287683?item=287696.

—. “Rest.” Goblin Market and Other Poems, London, 1862, pp. 116. Baylor University Digital Collections, digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/goblin-market-and-other-poems-by-christina-rossetti-with-two-designs-by-d.-g.-rossetti/287683?item=287696.

Notes:

[1]Since line numbers are unavailable in most of the sources cited, I have here opted to use page numbers in all parenthetical citations as most helpful for finding the quoted passages in these particular editions, both in print and online.