A Guide to the Holy Eucharist. By William J.E. Bennet. Two Volumes. London: Printed by W.J. Cleaver, 1842. (Armstrong Browning Library, Anthem Archive: ABL Rare X 264.036 B472g 1843)

The Book of Common Prayer and the Administration of Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the United Church of England and Ireland. One Volume, unpaged. Oxford: Printed at the University Press, 1864. (Armstrong Browning Library, 19th Century Collection, Coleridge Family Books: 19thCent BX5145 .A4 1864).

Flexibility and Rigidity in Anglican Devotional Texts: The Book of Common Prayer and A Guide to the Holy Eucharist

By Jonathan Diaz

The Preface to the 1662 Book of Common Prayer declares that “it hath been the wisdom of the Church of England, ever since the first compiling of her Publick Liturgy, to keep the mean between the two extremes, of too much stiffness in refusing, and of too much easiness in admitting any variation from it” (Book of Common Prayer). Here, then-Bishop of Lincoln Robert Sanderson certainly has in mind the volatile ecclesial and political conflicts of the early modern English Church (Haigh 32). However, even more than this, the preface strikes at a vital question for any worshipping community: how can individual devotional practices be reconciled to a shared life of worship? In other words, exactly how common must common prayer be? Two texts housed in the Armstrong Browning Library can demonstrate how nineteenth-century Anglicans took it upon themselves to navigate their own way between “stiffness” and “easiness” against which their tradition warned them. One, an 1864 copy of the Book of Common Prayer owned by Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s grandson Ernest, shows how families forged explicit connections between events in their own lives and the liturgies of the Church. Another, A Guide to the Holy Eucharist owned by Elizabeth Barret Browning’s niece Mary Altham, reveals the ways that the Anglican clergy would catechize their parishioners to facilitate their own participation with the set liturgies of the Eucharistic Rite. Because the question of communal and individual devotion rests not only on ecclesial and credal commitments, but on the lived experiences of those within these communities, the testimonies of these texts are invaluable for any seeking to resolve it.

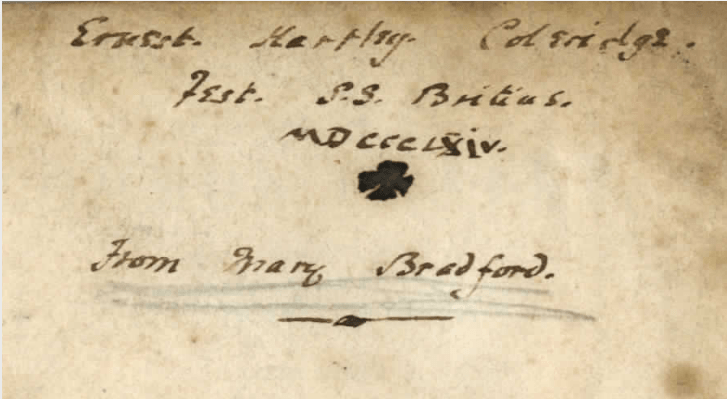

On November 13th, 1864, a young woman named Mary Bradford presented a young man with a copy of The Book of Common Prayer. The young man in question was Ernest Hartley Coleridge, the grandson of romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Twelve years later, the two would marry (Friends of Coleridge). An autograph dedication on the inside cover notes that the book was dedicated to Ernest on the Feast of St. Britius, better known as Brice of Tours, a fifth-century bishop little known outside of France and England (Butler).

This dedication is highly suggestive. To begin, the choice to record the date by reference to the feast of St. Brice demonstrates that, for Christians like Mary Bradford, the sacred calendar of Christian feasts was the instinctive reference point for placing an event in time. To properly place an event in time meant to connect it to the life of a Christian saint. Further, in this instance, this event is not only recording the gift of a text, but the relationship between two people who would eventually marry and start a family. As such, this particular Book of Common Prayer becomes integral to the marriage and family of Ernest Hartley and Mary Coleridge. We can see, then, how thoroughly this liturgical text was interwoven with the fabric of their own lives.

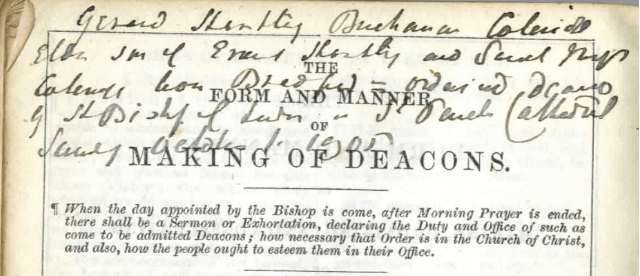

This dynamic is replicated when, over four decades later, Ernest and Mary’s son Gerard entered ordained ministry. On the first page of “The Form and Manner of Making of Deacons,” the following autograph inscription appears:

Eldest son of Ernest Hartley and Sarah Mary

Coleridge (illegible) = ordained Deacon

By the Bishop of London at St. Paul’s Cathedral

Sunday, October 1. 1905

The autograph, which appears to be written in a different hand than the dedication, makes an even more suggestive connection between personal history and liturgical practice. Where Mary’s dedication applies to the entire text, this inscription ties a personal event to a particular ceremony in the Church of England. The ordination service for deacons was permanently marked for the Coleridge family: at any subsequent diaconal ordination, to follow along with the ceremony would mean to recall Gerard’s ordination. We might consider Ernest and Mary Coleridge to have navigated between personal and communal worship, not by deviating from established rites, but by literally re-inscribing those rites with personal significance.

Our copy of A Guide to the Holy Eucharist can also shed light on how nineteenth-century Anglicans incorporated their own private devotions into the shared patterns of a corporate liturgy. This guide was written by William James Early Bennet, who was described in a biography by his nephew as “One of the most energetic restorers of the paths, one of the first to see that the doctrines of the faith must be set forth by the ceremonial of the Church, one engaged in a lifelong struggle to free the Church from the tyranny of the State, one of the most prominent of those whose work it was to carry the teachings of the Oxford leaders into the practical daily life of men” (F. Bennet, preface). As a contributor to the Anglo-Catholic and ritualist movement within the Church of England, Bennet was a fierce advocate for the compatibility of the doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist and the Anglican formularies. He was so involved in these controversies that in November of 1850, partly motivated by incendiary cartoons in Punch, an anti-Catholic mob attacked St. Barnabas church, where Bennet served as curate (F. Bennet, Ch. VII). Bennet would resign his curacy the following year. The volatility of these theological disputes demonstrates, not only Bennet’s significance as a figure, but the stakes of determining one’s own participation in Anglican worship. To worship in a certain way meant not only joining one worshipping community, but risking the ire of another.

Bennet’s guide seeks to address problems he sees in lay people’s attitudes towards the Eucharist in the Church of England. Notably, his work is not primarily a treatise, but a series of instructions to the lay person preparing for and engaging in the Eucharistic service. He writes that the first volume of his work is “intended for private use” and provides “a course of preparation and self-examination” (W. Bennet, vi–vii). The second volume “is intended to be used in the Church” and involves “a close direction to the communicant as to the meaning of the various parts of the service” (W. Bennet, vii–viii). Taken together, both volumes seek to use private devotion to facilitate greater participation in the Eucharistic service. Referring to practices described in the first volume, Bennet writes that “it is not meant that every prayer and meditation should be used at every time of communion, but … they are merely put before such persons as may need some little help in their devotions from want of habit or facility in using private prayer to Almighty God.” Bennet explicitly sees his guide as a flexible set of practices, from which Christians may choose those beneficial to their participation in corporate worship.

This particular edition of Bennet’s guide shows that it was used in just this way. The book belonged to Mary Altham, a niece of Elizabeth Barret Browning, and was presumably a gift from Altham’s parish priest. An autograph dedication (repeated verbatim at the start of both volumes) reads as follows: “Mary Altham, from her affectionate friend and pastor William M Lance May 11th 1868.”

The date given here is significant in light of other inscriptions on the book. A book plate on the inside cover provides the dates of Altham’s Baptism, Confirmation, and First Communion. Like Ernest Hartley Coleridge’s Book of Common Prayer, Altham’s copy of A Guide to the Holy Eucharist records her life through recording her participation in the Sacramental life of the Church.

When we compare the dates on the book plate to the date of the dedication, we can see that Lance presented the book to Altham on the day of her confirmation, which preceded the day of her first communion—May 24th 1868—by nearly two weeks. The presentation of the book by Altham’s pastor at this time suggests that this was not simply a readily available devotional text, but an intentional choice made to prepare Altham to receive the Eucharist for the first time. In Altham’s immediate religious community, the formation of personal patterns of devotion was considered a necessary preparation for joining the Sacramental life of the Church.

While there are no other autograph inscriptions in Altham’s copy of the Guide to the Holy Eucharist, we are not completely without clues about her use of the book. Two illustrated cards can be found tucked inside the front cover of the second volume.

The first of these shows the resurrected Christ rising from a tomb, accompanied with a Latin inscription, meaning “(He) has risen, just as He said. Alleluia!” The second shows the tower of an English Gothic church and features a short, unattributed poem stating “God bless thy year!” The inclusion of these cards in the book suggests that Mary Altham or some other reader considered the book a receptacle for all sorts of devotional aids. Perhaps in line with Bennet’s instruction to select the practices that help in their devotions, the reader has interpolated his text with external images to provide that help.

These two texts provide vital insights into the ways some nineteenth-century Christians navigated the tension between private and communal worship in the Church of England. We might do well to recognize that the incorporation of private devotion and experience into a liturgical pattern of worship did not necessarily require deviation from that pattern. Rather, Christians like Altham, Bennet, and the Coleridge family used an innovative and flexible set of practices to bring their private lives into the shared rhythms of their worshipping community. This insight has profound potential to impact our notions of the history of religious practice. Philosophers as different as Charles Taylor and Roland Barthes justifiably contend that the Protestant Reformation is instrumental in shifting religious experience out of the communal sphere and into the personal. While this narrative has merits, it can obscure the concrete practices undertaken by religious individuals and communities to reconcile personal and communal worship. The Anglican tradition, which has long employed the rhetoric of mediation between extremes, offers a unique testimony of such practices. Through close attention to these and other devotional texts, we might hope to gain a fuller account of how past generations of religious believers conceived of themselves simultaneously as individuals and as members of a worshipping community.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Rustle of Language, translated by Richard Howard, pp.49–55. Farrar, Strauss, Giroux 1986.

Bennet, F. The Story of W.J.E. Bennet. London : Longmans, 1909. Project Canterbury, Accessed March 02. 2022

Bennet, William J.E. A Guide to the Holy Eucharist. London : W.J. Cleaver, 1842.

Butler, Alban. “Saint Brice, Bishop and Confessor.” Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Principal Saints, 1866. CatholicSaints.Info. Accessed March 02, 2022.

Doe, Norman. “Robert Sanderson (1587-1663).” Ecclesiastical Law Journal, vol. 24, no. 1, 2022, pp. 68-86., doi:10.1017/S0956618X21000752

Haigh, Christopher. “Liturgy and Liberty: The Controversy over the Book of Common Prayer, 1660-1663.: Journal of Anglican Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, 2013, pp. 32-64., doi:10.1017/S1740355312000344

Platt, Sarah. “Samuel Taylor Coleridge Family Tree.” The Friends of Coleridge, www.friendsofcoleridge.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=251:coleridge-family-tree&catid=2:news. Accessed March 02. 2022

Taylor, Charles. “Western Secularity.” Rethinking Secularism, Edited by Calhoun, Craig, et al. Oxford UP, 2011.

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the United Church of England and Ireland. Oxford UP, 1864.