Matthew 21: 33-46

This text is used for the Lectionary Year A on October 8, 2017.

Klyne Snodgrass has written that this is “one of the most significant, most discussed and most complicated of all the parables.” Within its mysteries, this parable provides an opportunity to consider issues of faithfulness, stewardship, sin, judgment and God’s unrelenting grace. Familiarity with its Hebrew Bible and Jewish context will help us as we rise to meet the challenge of sharing it with our congregations. May those who have ears to hear receive every nudge this story has to offer them this week.

Klyne Snodgrass has written that this is “one of the most significant, most discussed and most complicated of all the parables.” Within its mysteries, this parable provides an opportunity to consider issues of faithfulness, stewardship, sin, judgment and God’s unrelenting grace. Familiarity with its Hebrew Bible and Jewish context will help us as we rise to meet the challenge of sharing it with our congregations. May those who have ears to hear receive every nudge this story has to offer them this week.

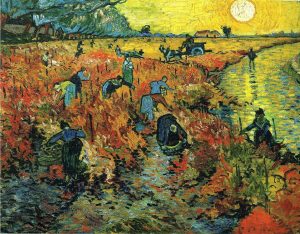

Matthew certainly draws a connection between this parable and the song of the vineyard in Isaiah 5. Exploration of this connection enriches our understanding of the symbolism in the parable and helps us see what Jesus isn’t saying. Historically this story has been used to emphasize supersessionism as an illustration of God’s judgment upon Israel which resulted in Israel’s role in God’s Kingdom being transferred to the Church. One could interpret the parable this way. God sent them prophets right up to John the Baptist. They persecuted and rejected every single one. Now God, the owner of the vineyard, has sent God’s own Son whom they will also despise and reject. What do you think God will do to them?

This interpretation has been used over the years to justify anti-Semitism, with one obvious example coming from Josephus. He described the Romans using war machines to lob large stones into Jerusalem during the siege of the city: watchmen were accordingly posted by them on the towers, who gave warning whenever the engine was fired and the stone in transit, by shouting in their native tongue, “the son is coming,” Before and beyond this kind of inappropriate application, this is a reading neither Isaiah’s imagery nor the larger context in Matthew supports.

In Isaiah, the vineyard is Israel. The evil in this parable is not being enacted by the vineyard itself, but by its wicked tenants. At the conclusion of the parable, Matthew says the chief priests and the Pharisees “knew he was talking about them. (21:45)” The critique is therefore not directed at the vineyard but at the stewards of it, i.e., Israel’s religious and political leaders.

In our own context, this calls us to consider our own stewardship. Scripture tells us that we teachers will be judged more strictly for what we’ve been given to steward. (James 3:1) This parable ought to prompt those of us who are “religious leaders” to handle our jobs with a bit more care this week. No pressure. Stewardship is our privilege, but not ours alone. Our parishioners all belong to a royal priesthood. (1 Peter 2:9) Each person in the pew has been given gifts, abilities, opportunities, resources, responsibilities, and relationships that are theirs to steward, just as each congregation has a role in local and global stewardship given to the Church by God. In fact, one might consider new, modern possibilities for the vineyards in each of our lives. Is your vineyard your family, your job, your church; your world? Perhaps before Israel, the first vineyard was Eden, a symbol for the untouched world we were all given to steward and for which we are all now tasked to work with God to restore and redeem.

As we consider the responsibility of stewardship, the parable also points out the risks. The tenant farmers kill two sets of servants sent by the landowner before finally persecuting and killing the son. Why would they do something like that? In the Jewish world, there were laws that indicated possession could lead to ownership. It’s possible they killed the absentee owner’s servants to keep him at bay and then assumed the son’s appearance meant the landowner was dead. If they killed the only heir, then, they could fully claim ownership of the vineyard. The flowering of this evil objective likely began long before the appearance of the son as a result of growing, mistaken identity.

In his book “The Waiting Father,” Helmut Thielicke reminds us these tenants were employees, not contractors. This land does not belong to them. However, over time, they began to claim everything as their own: Their capacity to work, their output and finally the whole scene of their work life – namely the vineyard itself. Their grievous and habitual sin was rooted in their growing tendency to see themselves as owners, not stewards, of the gifts in their life. There’s a sermon in there somewhere. One that must be saturated with the larger, more striking gospel point: God’s grace is risky and relentless.

What kind of landowner would, after sending two sets of servants to their death, choose to send his own son to these greedy, bloodthirsty, out of control tenants? A stupid one? Perhaps. But we’re supposed to read the parable as part of the larger narrative of God and God’s people, where we are the unfaithful Gomer and God, Hosea, who despite our chilling, habitual unfaithfulness, relentlessly pursues us again and again and again, no matter the personal cost. It’s a risky, ill-advised love of which we continue to be the undeserved recipients.

Dr. Jason Edwards

Dr. Jason Edwards

Senior Pastor

Second Baptist Church, Liberty, MO

jedwards@2bcliberty.org

Tags: Stewardship, Judgement, Grace, Love, Parable, Supersessionism