This summer, The Texas Collection was fortunate to have four graduate students working with our staff and in our collections. We asked them to share a little about their projects and what they have learned. Last month we heard about Baptist collections and athletics film; this month, we’ve got the papers of a beloved Baylor president and of a Central Texas archaeologist/lithographer/Renaissance man.

My name is Amanda Mylin, and I am a history master’s student from Pennsylvania. This summer I had the privilege of working for The Texas Collection as the D.M. Edwards Library Intern. (I previously was a graduate assistant at the TC for the 2014-2015 year, working with Amanda Norman and Paul Fisher, primarily on Baylor University records.) My major project this summer was to process and rehouse the Samuel Palmer Brooks papers. This collection is well-used by researchers, necessitating preservation work and an electronic finding aid.

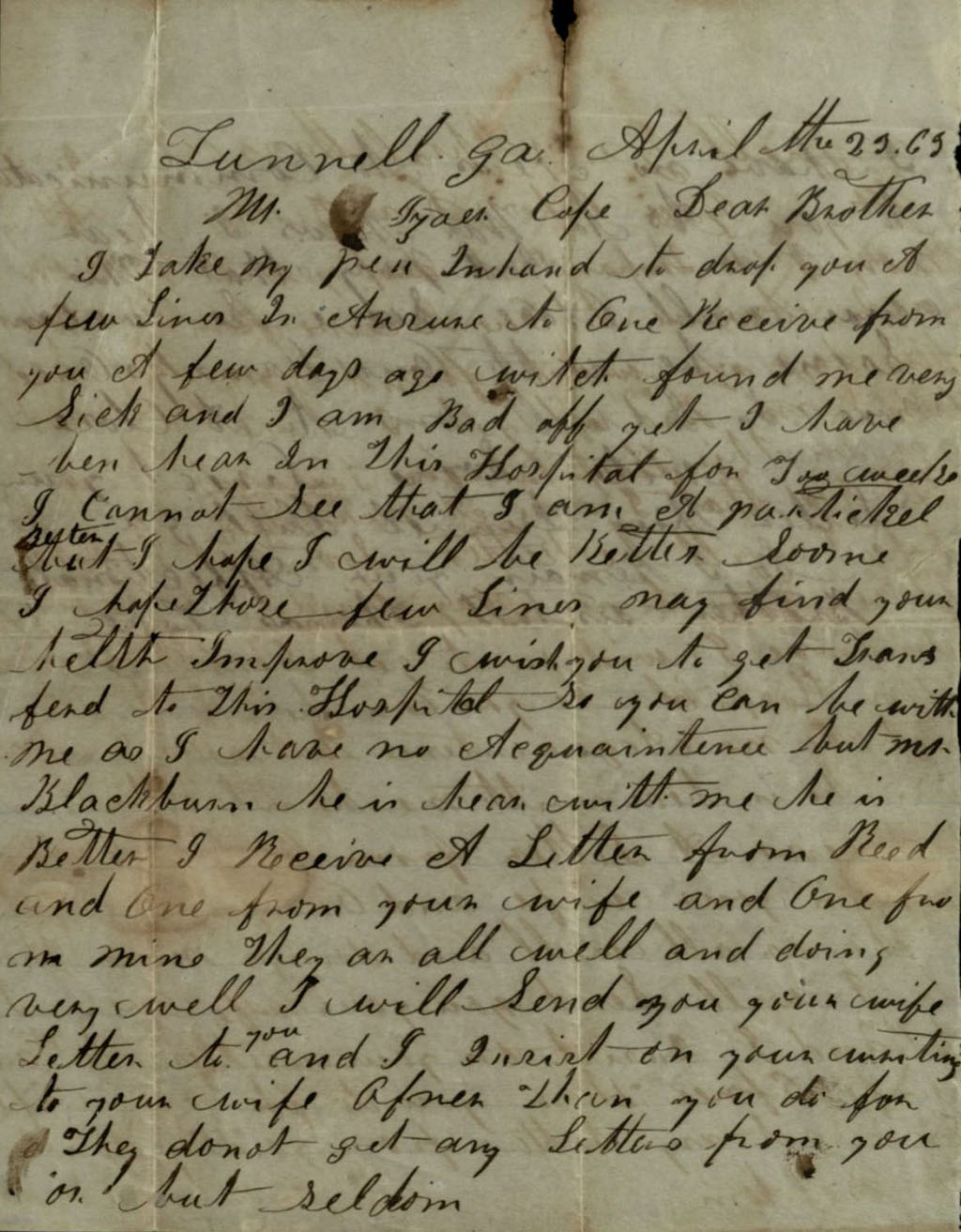

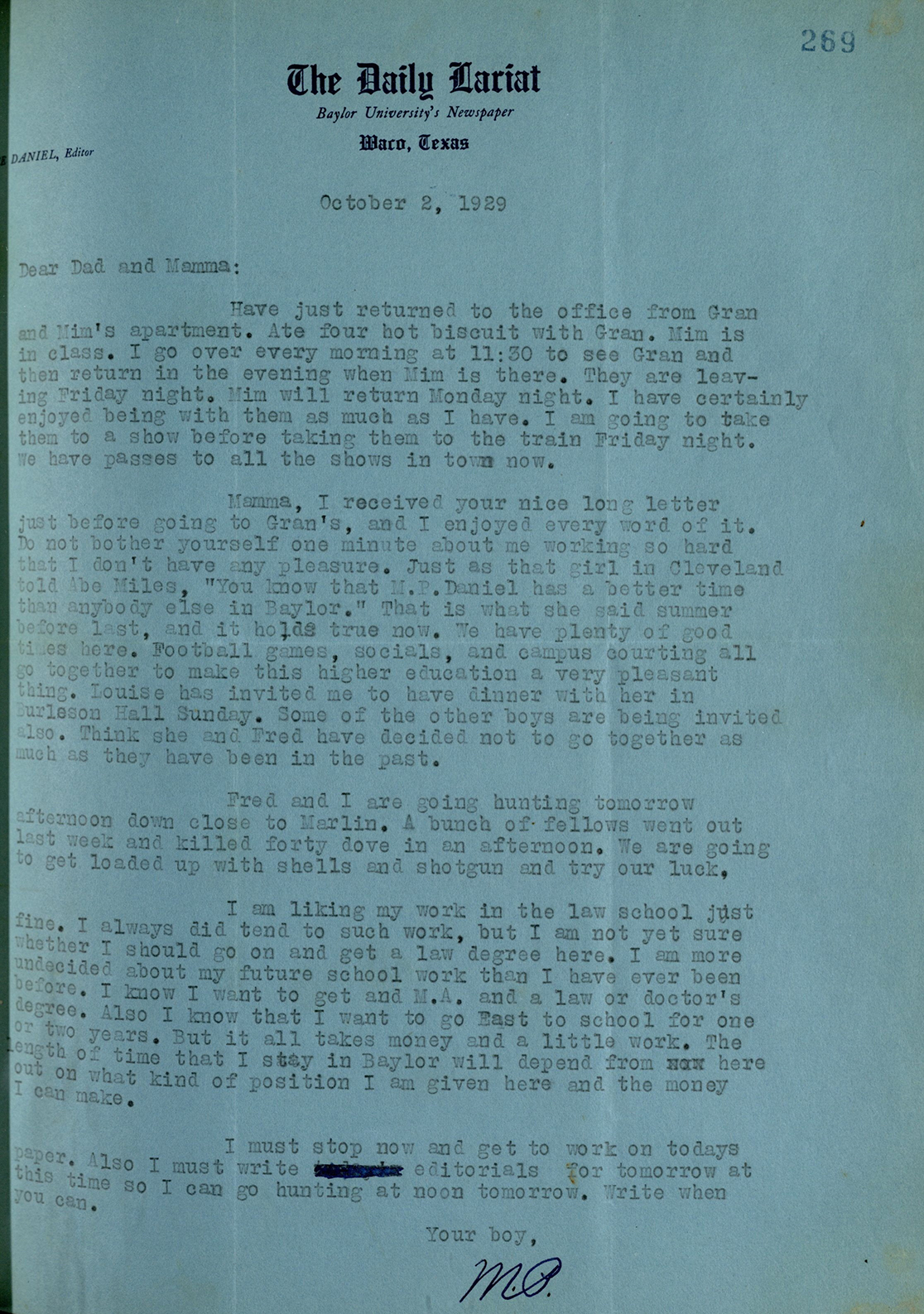

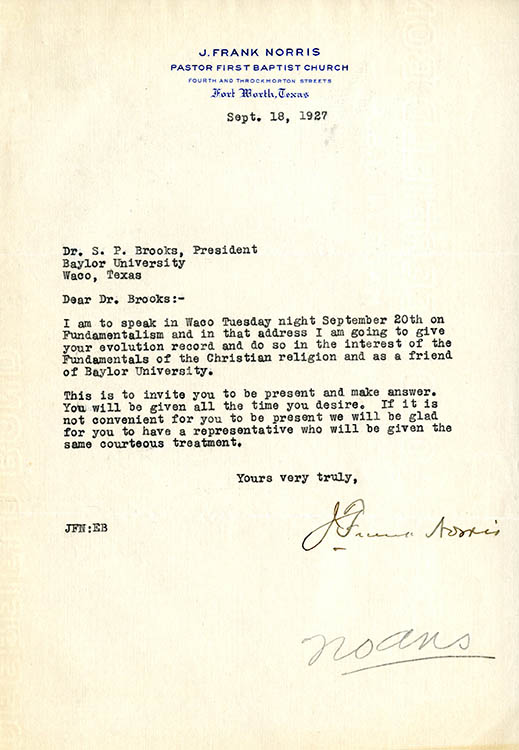

Brooks served as Baylor’s president from 1902 to 1931. His presidency saw the heyday of the evolution controversy between Fundamentalists and Modernists, prohibition, women’s suffrage, and the onset of the Great Depression. Rehousing this collection afforded interesting glimpses at major twentieth century historical moments through the lens of Baylor and Brooks.

I also learned much about Baylor in the early twentieth century, including the students’ fondness for “Prexy,” as they lovingly called him. His dedication to Baylor students and the Baptist community was also evident through the sheer number of flowers, condolence letters, telegrams, and newspaper articles surrounding his death. Many articles discussed his devotion through his decision to sign the 1931 diplomas despite his rapidly failing health.

Now that the papers are rehoused more comfortably and the finding aid updated, the collection amounts to 59 document boxes and 2 oversized boxes. Since I hope to continue working in special collections in the future, I had much to gain from this summer’s project. I encountered situations like insect-chewed papers, learned what happens to deteriorating silver gelatin photographs, and experienced tackling a very large collection, among other things. Upon completion of this project, I finished out the summer by processing a new collection, the papers of Diana Garland, former dean of Baylor’s School of Social Work.

We’re fortunate to have Amanda stay on with Baylor awhile yet, although not at The Texas Collection. After she graduated in August, she began work as a project archivist working on the Chet Edwards collection at the Baylor Collections of Political Materials.

~

Hello, Texas! My name is Casey Schumacher and I’m a Museum Studies graduate student from Central Illinois. I started working with Benna Vaughan when I moved here in August 2014 and was able to work with her on manuscripts collections through this summer. As a non-Texan, every day is an opportunity to learn something new about this state and its people.

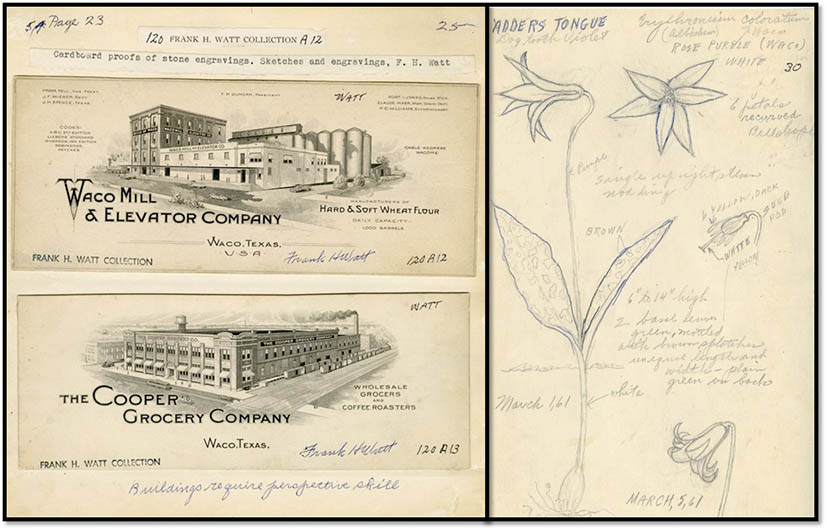

My primary summer project involved processing the Frank Heddon Watt collection. Processing a collection involves placing the collection in order so researchers can access it easily, putting the materials in new folders and boxes and uploading information about the collection online. This collection ended up filling 46 document boxes, so processing it took longer than some of my smaller collections.

With large collections like these, consistency is vital, and it’s best if one person sees the whole project from beginning to end. I began processing the Watt papers after they had already been arranged a couple of times, and a previous assistant had started a third arrangement but only made it halfway through the collection. In other words, the whole collection was a mess. I ended up redoing the entire collection so it would all be processed the same way and more efficient for researcher access.

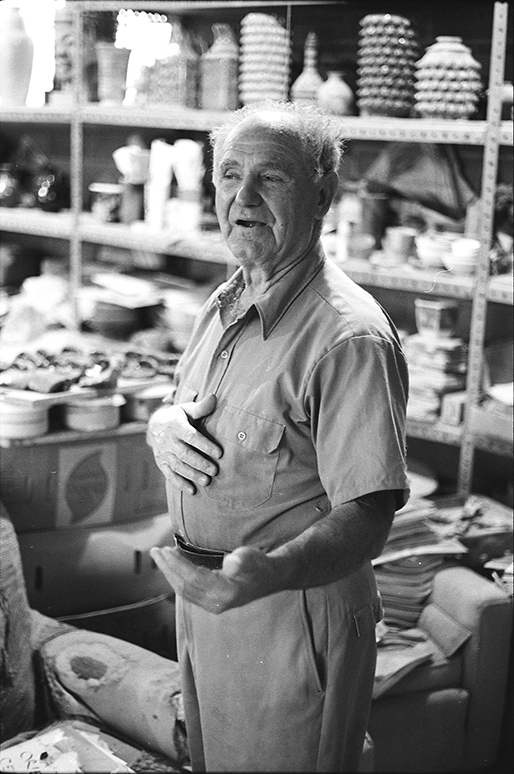

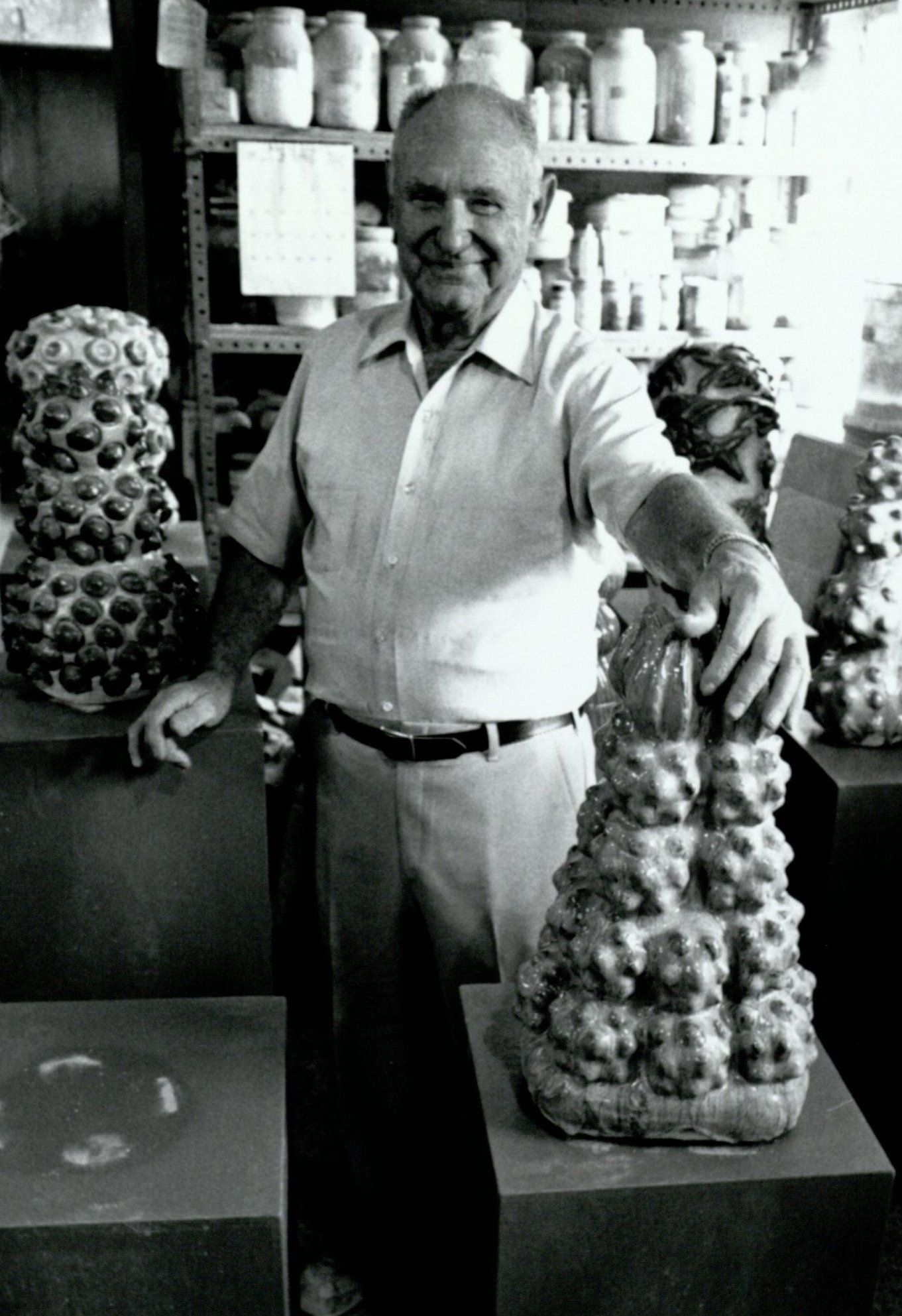

Watt (1889-1981) was a jack-of-all-trades, and his collection included 3D objects, photographs and notes from archaeological digs in Central Texas, as well as several boxes of lithography samples, sketches, and instruction books. Once the project was completed, I felt like a bit of a professional in each area he researched!

I really enjoy working at the Texas Collection and when I return in the fall, I’ll be working with different collections and learning archival techniques new to me. Working with a diverse selection of collections will also help me prepare for the Certified Archivist Exam after I graduate from Baylor. While I won’t have the opportunity to dig as deep into a specific subject or person as with larger collections, I’m excited to learn more about Texas history and help make these collections accessible for students and the broader community.