By Paul Fisher, Processing Archivist

In our last post on BARD, we learned how to get to the database, where the finding aids are to different collections, and how to navigate within the finding aid to find the materials you want to see. In this post, we will discover how subject terms work in BARD, how to print or make a PDF of your search results, as well as how to navigate to related web pages.

In our last post on BARD, we learned how to get to the database, where the finding aids are to different collections, and how to navigate within the finding aid to find the materials you want to see. In this post, we will discover how subject terms work in BARD, how to print or make a PDF of your search results, as well as how to navigate to related web pages.

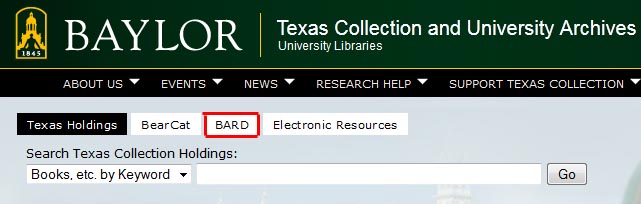

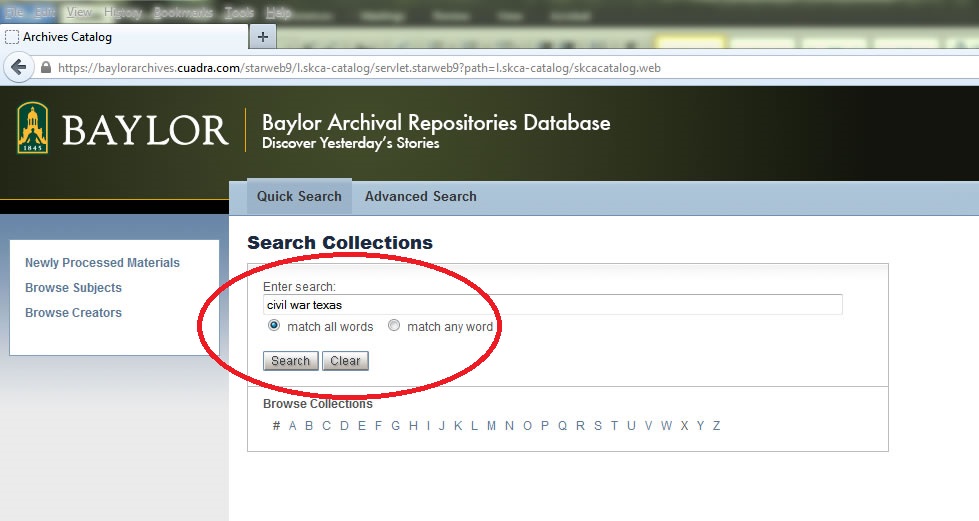

You can enter the BARD system by clicking the link on our home page. Once in the system, you have several options for finding resources. For this example, let’s say you want to see all the collections that have anything to do with Baylor University at Independence. To look for this, you could enter the words “Baylor at Independence” in the search field in the center of the screen.

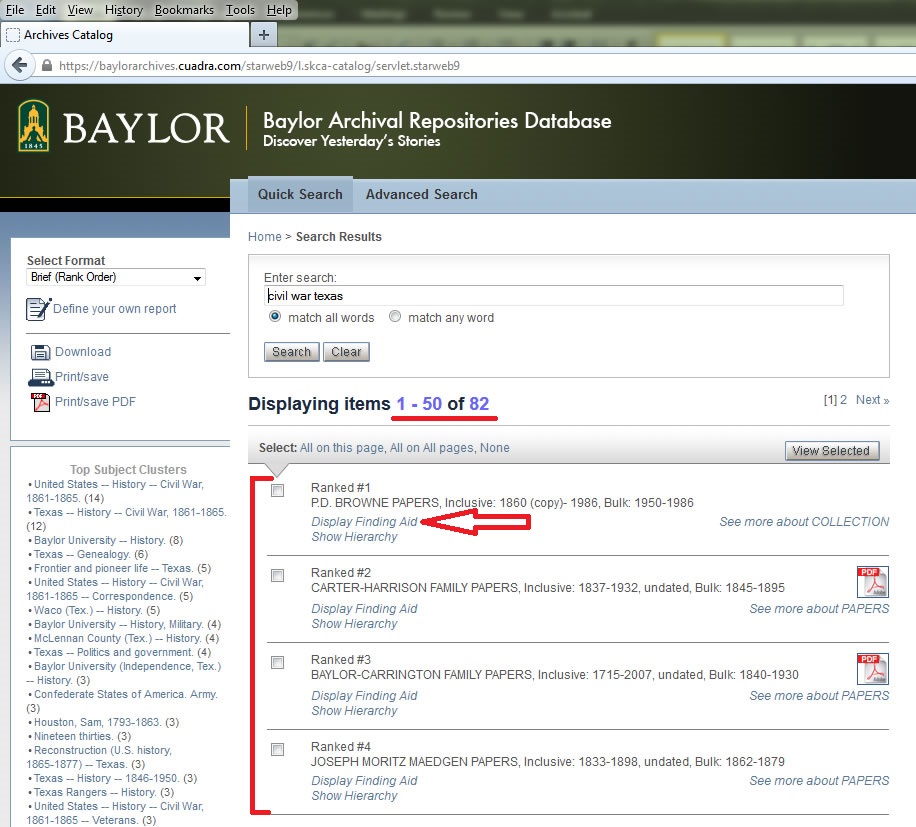

When I did this search, 55 results came up! Click “Display Finding Aid” under each entry to view further information about each collection.

Since we have thousands of collections in the database, you may wish to narrow your search by using the subject terms under the “Top Subject Clusters” on the left side of the page.

For example, you could click on the “Baylor University – Presidents” term to bring up just the collections on Baylor presidents that have to do with Baylor at Independence…

…and this page will come up. Displayed are the five collections that have to do with Baylor University at Independence and also have something to do with Baylor presidents during that time.

You can click the “Select Format” menu on the upper-left side of the page to toggle between different views (Brief, Preview, or Full) that will give you more or less information. (The view above is Preview.)

Let’s say that you have found some collections that you would like to examine at The Texas Collection. Since you are looking for something to do with Baylor University presidents at the time Baylor was at Independence, you probably want to see all five collections listed here, but you may not have time right now to peruse all the finding aids. Rather than writing down all five collections, you can print or save this list. Click on the “Brief” view under “Select format” on the left, and then click “Print/save” to open a window to print, or Print/save PDF to open a file to save.

By opening this view, you can then print using your browser’s print function, or save a PDF file to your flash drive. Now you can remember which specific finding aids to look at later and figure out which boxes you’ll need to use, which will help you set your research appointment with our staff.

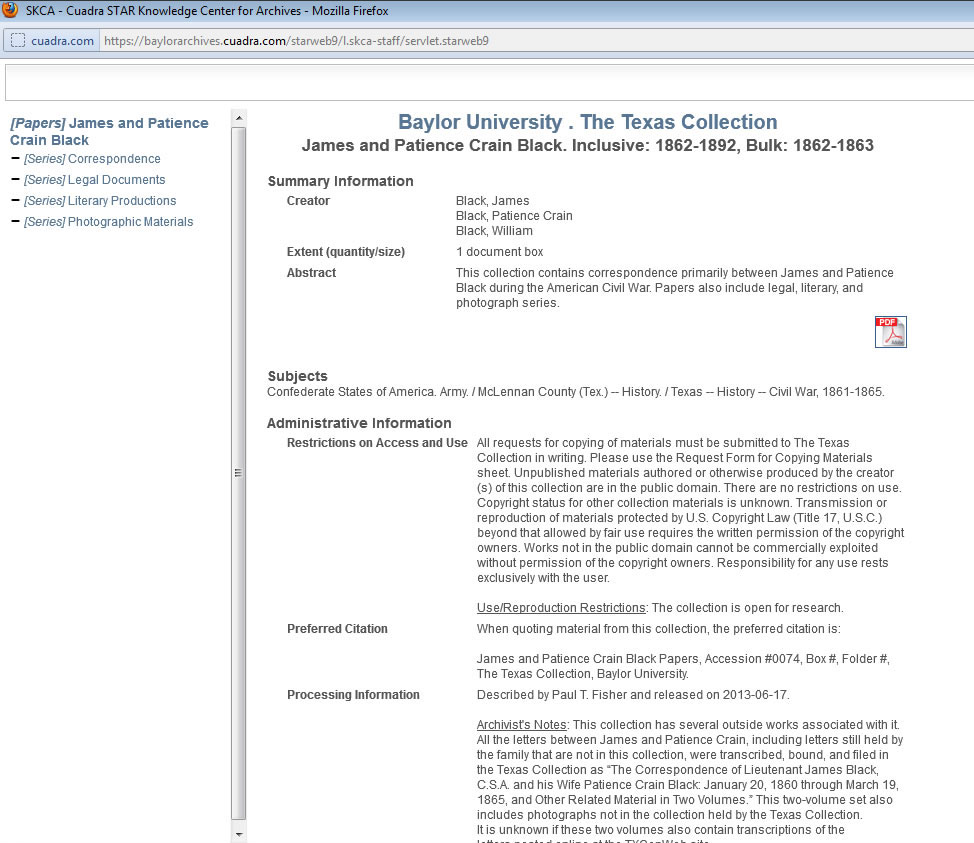

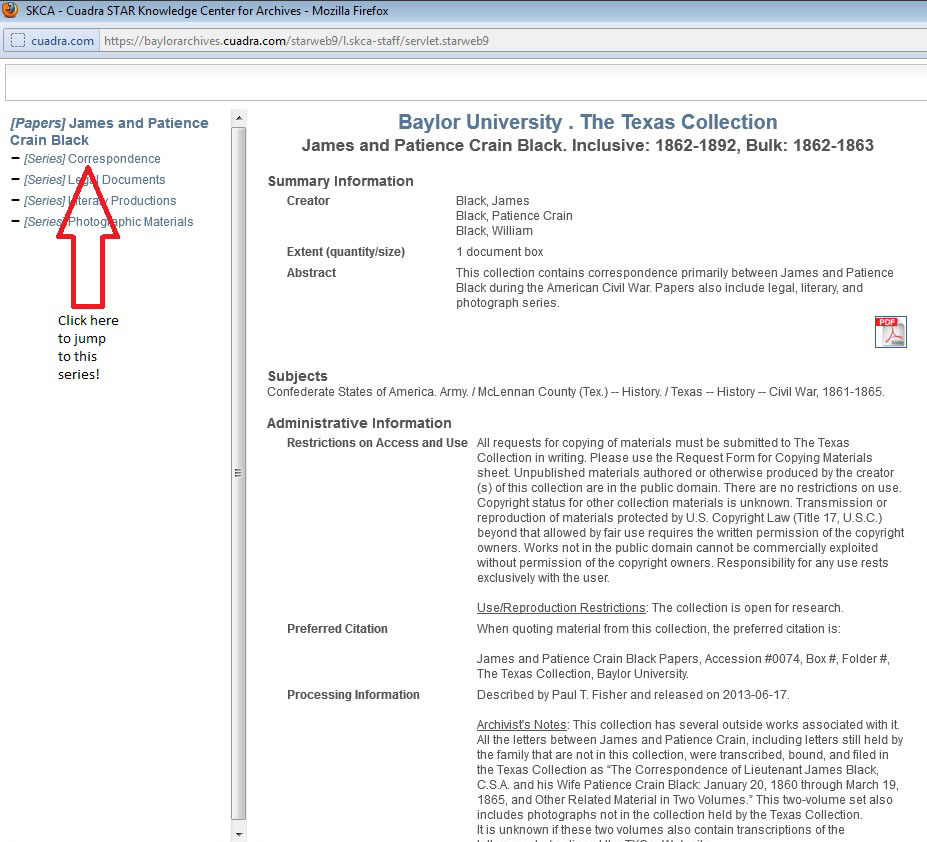

You can also explore collections that are filed under the same search terms from within a finding aid. Let’s say that you were intrigued by the BU Records: Baylor Historical Society finding aid from above. Go back to the main search page from before, and click on “Display Finding Aid.”

From within this window, go down to all the terms in blue under “Subjects.” These are all keywords that you can use to find similar collections within The Texas Collection. For example, you can click “Baylor University – Presidents” to see all the collections that we have indexed with that term.

This way of moving across connected collections can be very valuable, since many of our collections are connected to other collections.

You can also see resources consulted for the finding aids that you see in BARD. For example, let’s say you were reading along in the BU Records: Baylor at Independence finding aid.

When you get down to the “Related Resources” part of the finding aid, there is a list of resources consulted for this finding aid. Many of these are in blue to indicate a hyperlink and can be clicked to take you directly to that resource or a catalog listing to tell you how to find it. If you clicked on “Murray, Lois Smith. Baylor at Independence. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 1972” the link would take you to that resource in BearCat, our library catalog. You would then have all the information you would need to request that book the next time you come to The Texas Collection.

When you are done viewing finding aids in BARD, be sure to close down the system properly. In the main search page, on the upper right corner, click the red “Log Out” to exit from BARD. Leaving the system in this way is very important to ensure the proper functioning of the system.

Stay tuned for one more entry with helpful hints about using BARD!

Stay tuned for one more entry with helpful hints about using BARD!

In November 2013, the Baylor University Libraries officially opened BARD (Baylor Archival Repositories Database). This is the second post in an ongoing series to celebrate the opening of this digital research database, and show some of the new ways to find resources.

We have many researchers visit The Texas Collection who are working on book projects, and we are always so excited when we hear one has been completed. Dr. Nancy Goodloe, emeritus professor of health education at Baylor, visited our collection several times while working on Before Brittney: A Legacy of Champions. Her recently published book explores the path from the first female varsity letter winners in 1904—and then there were no more varsity letters awarded to women until 1976—to the national prominence Baylor women’s athletics enjoys today.

We have many researchers visit The Texas Collection who are working on book projects, and we are always so excited when we hear one has been completed. Dr. Nancy Goodloe, emeritus professor of health education at Baylor, visited our collection several times while working on Before Brittney: A Legacy of Champions. Her recently published book explores the path from the first female varsity letter winners in 1904—and then there were no more varsity letters awarded to women until 1976—to the national prominence Baylor women’s athletics enjoys today.