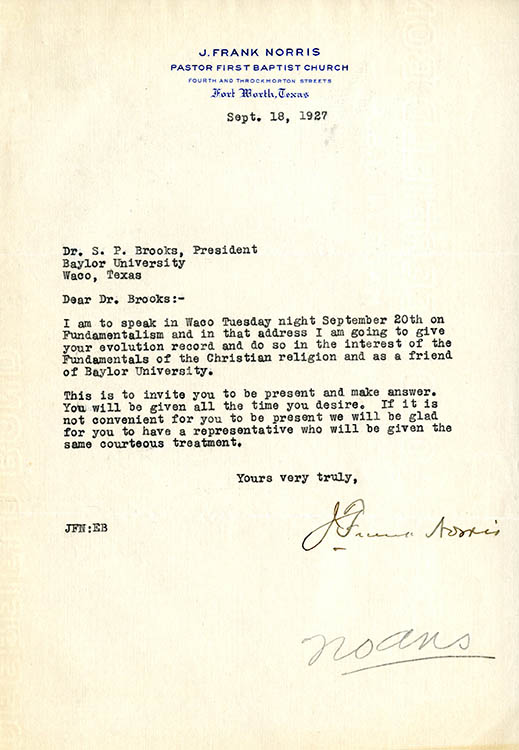

By Casey Schumacher, Texas Collection graduate assistant and museum studies graduate student

In July 2015, President Obama declared the Waco Mammoth Site a National Monument, and Central Texas rejoiced. About the same time, a less well-known archaeological find occurred at The Texas Collection as I began processing the Frank Heddon Watt collection. Among his many vocations, Watt was a founding member of the Central Texas Archaeological Society in 1934. And so, while the National Park Service was sharing images and samples of mammoth bones, I was discovering photos of human remains and hand-drawn maps of their burial sites. Over the next eight months, I realized the Frank Watt collection had just as much to teach our archival staff as it had to teach our patrons.

Archives are not the only repositories for Native American materials, nor were they the first to ask questions about how to properly handle human remains. In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) laid the groundwork for museums to examine carefully the state of Native American objects in their collections. The primary goal of NAGPRA was to assure appropriate and respectful use, care and (in some cases) repatriation of sacred or culturally sensitive objects, such as human remains, funerary objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. Museum visitors would notice these changes the most in exhibits that included Native American mummies, pipes, or costumes used for sacred rituals. Behind the scenes, this new legislation required museum staff to complete copious amounts of paperwork and extra work to ensure they were up to NAGPRA’s standards. However, NAGPRA only applied to museums; it offered no suggestions or standards for archives like The Texas Collection or for archival collections like that of Frank Watt.

As an institution in the public trust, The Texas Collection believes it should maintain a high ethical standard, even if it is not bound by law to do so. As a result, I believed the images of human remains and the detailed reports of their excavation deserved to be stored and handled both carefully and respectfully. Ultimately, my supervisor and I created a new policy for The Texas Collection; namely, that in the spirit of NAGPRA, archival collections with culturally sensitive materials would be open for public research, but that researchers should maintain a quiet, respectful attitude during their research and that scanning or digitizing culturally sensitive materials would be strictly prohibited.

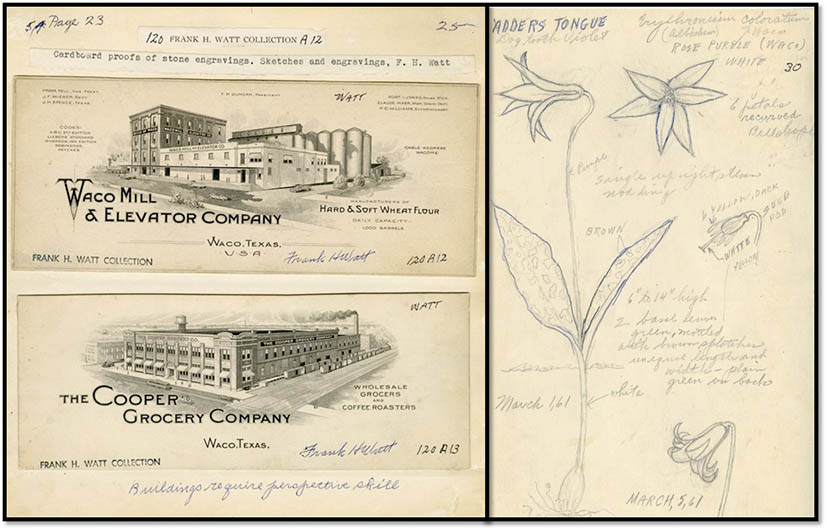

Now that the entire collection is open for research, the Frank Watt collection has much to offer besides archaeological materials. Watt held degrees in lithography and music, as well as teacher’s certification for public school music. He was an avid stamp collector, artist, and cello player. He worked as a printer, stone engraver, hotel serviceman, tree surgeon, and music teacher in Kentucky, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, and New York. In addition, his military service during WWI included field printing and working as an aircraft mechanic near Houston. In other words, Watt was a jack-of-all-trades and master of several. In his collection, researchers will find samples and collected pieces of lithography and stone-engraving, sketchbooks from his art classes at Winona Technical Institute, and military-issued manuals of aircraft mechanics.

At the end of the day, collections like that of Frank Watt are extremely important for both researchers and archivists alike. Naturally, they offer extensive resources for students and professionals in several different fields. They also present an opportunity for archivists to explore how we maintain ethical and professional standards in our institution and help us educate the public about why we do what we do.

Sources

Bischof, Robin E. “Boxes and Boxes, Missing Context and an Avocational Archaeologist: Making Sense of the Frank Watt Collection at the Mayborn Museum Complex.” Master’s thesis, Baylor University, 2011.

Bosque Museum. “Ancient Archeological Site on Exhibit at the Museum.” Bosque Museum. Accessed August 8, 2015. http://www.bosquemuseum.org/hornshelter.htm