This post was written by Horace Maxile, a student in the Museum Studies program. Horace recently completed a five-month independent study at The Texas Collection focused on archival work including processing, reparative description, preservation, arrangement, and description. He has written the following reflection, recalling how he became interested in archives as well as some of the lessons he learned in his studies.

My interests in the written traditions of black music, primarily classical pieces by black composers, date to my undergraduate years. As I enter my third decade in the academy, most of my scholarly work involves musical analysis and thinking through extramusical contexts, such as historical and cultural considerations, I rely heavily on musical scores. My analytical endeavors as a young scholar did not explore much beyond the engraved score and commercially available recordings, but an appointment at the Center for Black Music Research challenged me to reconsider my approaches to research and to consider the value and versatility of archival holdings.

Yes, the archival bug bit me during my tenure at the Center for Black Music Research and I am now taking some time to scratch that itch. To say that I am budding at this point in my life and career might be somewhat tongue in cheek, but I am excited to learn about archives and archiving through my studies at Baylor University.

As part of an independent study that was hosted by Baylor’s Texas Collection, I was assigned three projects, all of which piqued my interests in various ways. One project was reparative description for a finding aid. My initial rationale for doing this was to rewrite the description/scope with my connections in mind as well as deciphering what the first preparer may have deemed as the primary “finds” within the collection. This project took me longer than expected because I thought it would be wise to look for connections—or perhaps themes—between the materials. However, I was reminded by my supervising archivist that I was to provide some historical context in the description and allow the details that surface from within the collection do the work. The first lesson: reparative descriptions could move well past the description when necessary, involving edits/rewrites at the series level and, sometimes, relabeling folders. That lesson also challenged me to reassess the subject headings as well, editing and adding a few of my own. Around six weeks after I finished this project, I was informed that a researcher wanted to use the collection for which I provided the reparative work. I would like to think that some of my work guided the researcher to something useful.

The other two projects required me to fully process small collections (assessment, folders, preservation, finding aid, etc.). One of the processing projects was an herbarium. Yes, an herbarium. Compiled in the 1940s by Fannie Mae Hurst, the collection of floral specimens suffered no major deterioration. Other than being nearly 75 years old and dried out, the wildflowers were in pretty good condition. The collection was created by a professor who taught biology at Baylor. My research for the biographical profile yielded fascinating stories about her journey through graduate studies to the professorate as well as suggestive commentaries that peered into plights of women in higher education during the middle decades of the twentieth century. My inexperience was challenged by my supervisor, as all the cool stuff I learned about the creator and the deeper dives into gender and equity that I wanted to take had little to do with the actual collection of floral specimens. So, lesson number two surfaced: bibliographic citations may lead the researcher into deeper dives and aspects of biography and social contexts, but archival descriptions (at all levels) prioritize the contents of the collection. This was a valuable lesson, but so was the brief jaunt into the primary sources that offered insight on matters regarding this woman professor and her tenure at Baylor University.

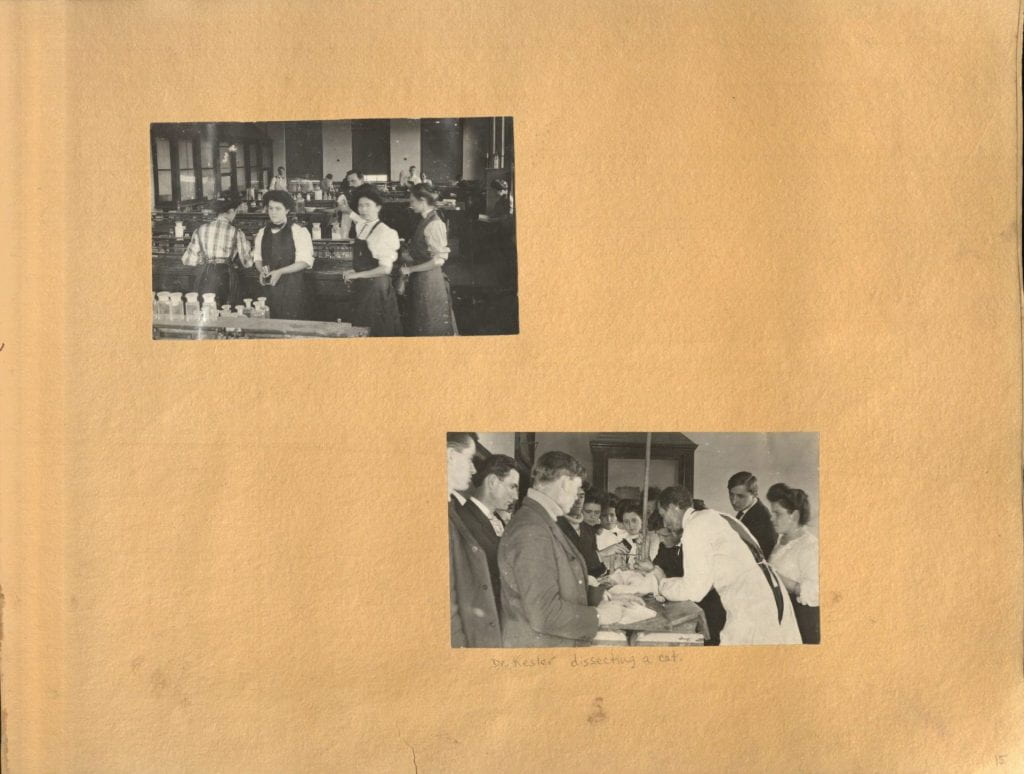

The other processing project involved scrapbooks and other materials in a collection by Ethel Standefer, another woman with academic and professional ties to Baylor University. She was a pianist who served with the fine arts faculty in the early decades of the twentieth century, but the collection has little to do with her activities as a performer. Whereas the scrapbooks contain concert programs and postcards from her travels abroad and numerous clippings related to musicians and composers of note, most documents that bear her name are professional certificates and autographs for which she is the dedicatee. The research that went into the biographical note places Standefer among the central figures in social and artistic circles in Waco during the 1930s and 1940s but, like Hurst, those contextual pieces were relegated to bibliographic citations. My predilections for music and musical histories were interrogated in the third lesson: collections contain their own stories—it is my responsibility to organize and describe materials so that researchers can get the information they need for their interests, not mine. Indeed, the scrapbooks in Standefer’s collection also reveal an interest in current events and politics, arenas where women during her time were not as publicly observed. I am much more than a musician, so why should Standefer be any less?

Lessons learned. Of course, there is overlap between the lessons and the collections with which I’ve worked and there are, indeed, lessons that were not mentioned in this reflection. The biggest takeaway thus far, in this personal and professional pursuit, is that un-learning that which “works for me” while learning new rationales and best practices for organizing archival materials is both humbling and unbelievably invigorating.