This post was written by Prof. Alex McNair of Baylor University’s Division of Spanish and Portuguese in the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures. An abbreviated version of this essay was presented at the Shakespeare First Folio faculty research showcase sponsored by Baylor Libraries on November 3, 2023.

In 2023 we commemorated the 400th anniversary of the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio. A folio is a large format book, the largest size they could print (folding the folio, or sheet of paper, only once). In 1623, seven years after the bard’s death, a folio-sized volume was published in London with thirty-six of Shakespeare’s plays. The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C. has the largest collection of Shakespeare First Folios worldwide, and you can page through a digital edition online. To see a First Folio in person, you might venture down to the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center in Austin, where they currently have three First Folios on display in an exhibit entitled “The Long Lives of Very Old Books” (August 19-December 30, 2023). The Baylor libraries do not have a Shakespeare First Folio, though the Armstrong Browning has many eighteenth-century editions. Initially on display to commemorate the quatercentenary of Shakespeare’s death in 2016, the ABL has reprised the exhibition in its treasure room this fall to celebrate the First Folio. The Texas Collection at Baylor also has fine examples of rare books from the early modern period. Last year, I had the opportunity to showcase the Collection’s rare books for students of Latin American Colonial Literature, and so I present here some observations on how these books can provide a different context for understanding the Shakespeare First Folio.

In the front matter of Shakespeare’s First Folio there is a prologue “To the great Variety of Readers” by John Heminges and Henry Condell. They write: “. . . the fate of all books depends upon your [the readers’] capacities: and not of your heads alone, but of your purses. Well! It is now public, and you will stand for your privileges we know: to read and censure. Do so, but buy it first. That doth best commend a book, the stationer says.” This is not the typical pitch that comes out of advertising agencies today, but it is refreshingly forthright. The compilers, who belonged to the King’s Men, Shakespeare’s former company, reveal the anxiety they must have felt after working with the stationers (i.e., booksellers/publishers) to produce a work this size. It entailed a substantial investment of material and labor, and stationers would have been concerned about covering their costs. Stephen Greenblatt, in his introduction to The Norton Shakespeare, calls the First Folio an “expensive venture” (65). Most of the stationers involved in the project must have thought it a gamble to publish a collection of contemporary drama. Lavish quarto- and folio-sized books were reserved for literature with more prestige: the Latin Classics, the King James Bible, Theology, History. Heminges and Condell even seem to acknowledge the dubiousness of Shakespeare’s plays as literature when they refer to them as “these trifles” in their “Epistle dedicatory.” Most plays in the seventeenth century, if they were printed at all, came out singly in cheap quarto editions–quarto size is achieved by folding the folio sheet twice (giving eight pages per sheet, four on each side).

Shakespeare’s Spanish contemporary, Miguel de Cervantes, published eight of his own plays, along with eight interludes, in a single collection in 1615, only because he couldn’t find a theater company to buy them. He had the luxury of seeing them in print at least: the booksellers could capitalize on his name recognition ten years after the publication of Don Quixote; most plays of the period, whether they were successful in the theater or not, never made it into print. Cervantes claimed to have written twenty or thirty plays in the 1580s alone; only two from that period survive. The case of Antonio de Solís, who wrote for the stage in Madrid between 1627 and 1661, is also illustrative. He was a regular in the literary salons of Spain’s capital during the reign of Philip IV and wrote often for the public theater. Like Shakespeare in his last decade as a playwright, Solís was frequently engaged by the court and his plays enjoyed private performances before the king. Solís quit writing plays after he was named to the post of Chronicler of the Indies in 1661. I like to think his play on Amazon warriors, staged in the palace theater at Buen Retiro in 1655, recommended him to the court as official chronicler: accounts from the New World often reported rumors of islands inhabited exclusively by a race of war-like women. Hernan Cortés, for example, writes in his fourth letter (October 15, 1524) that a captain brought him “word from the lords of the province of Ciguatán, who affirm that there is an island inhabited only by women, without a single man, and that at certain times men go over from the mainland and have intercourse with them; the females born to those who conceive are kept, but the males are sent away” (298-300). The Texas Collection has two copies of the work Solís composed as official chronicler: his History of the Conquest of Mexico. Originally published as a folio-sized volume in 1684 in Spanish, it was soon translated into English. As a handsome large-format book, the History enjoyed multiple editions across the next two centuries in at least five different languages. The Texas Collection has a 1724 edition of the Thomas Townsend translation. It is a lavishly bound copy with the fold-out illustrations and maps still intact. But Solís’s plays did not have the same fortune. A biography of Solís included in The Texas Collection’s 1776 Spanish edition of the History only mentions four plays, though modern scholars have recovered and edited eleven (see Fernández Carrión for a more recent biography of Solís). Shakespeare’s first folio, by contrast, preserves thirty-six plays; eighteen of which were not previously printed.

Without the first folio, we would not have plays such as Julius Caesar, Measure for Measure, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, or The Tempest. This is something of a miracle given the context of the book trade of the day, which prioritized the Ancients over the Moderns and, among the Moderns, preferred more international fare. As Greenblatt points out in his biography, Will in the World: How Shakespeare became Shakespeare, “Shakespeare’s reading, and indeed the entire Elizabethan book trade, was conspicuously international” (270). Many who could read, also read Latin. The grammar school that Shakespeare attended as a child in Stratford taught Latin, not English Literature (Greenblatt, Will in the World 26-27). This is borne out in The Texas Collection’s rare books from the early modern period. The oldest printed book we have in The Texas Collection, a Latin geography by Pomponius Mela, also contains the Collection’s oldest map. Printed in 1482, ten years before Columbus’s voyage, the Collection’s edition of Mela’s Geographia reflects the world as Europe had understood it for more than a thousand years (Pomponius Mela was a Roman geographer of the first century AD). The Texas Collection also holds sixteenth-century editions of another famous Geographia: Ptolemy’s. They demonstrate the period’s deference to the authority of the written word, especially that of the Ancients. Claudius Ptolemy had written his geography and cosmography in the second century AD in Greek. By the fifteenth century, the work had been translated into Latin and was first printed in 1477. A 1482 Italian translation of Ptolemy probably influenced Columbus’s calculations, but Ptolemy’s Geographia would have been hopelessly out of date after modern cartographers, like Vespucci, mapped the Western Hemisphere in the early 1500s. Nonetheless, the Renaissance was loath to overthrow the authority of classical learning, and Ptolemy continued to be reprinted. The Texas Collection’s three editions of Ptolemy, the Latin Geographia of1562 and Italian translations from 1561 and 1598, the latter a folio edition, leaned on the Ancient authority of the Alexandrian Greek’s name, but added maps and updated navigation charts that included the Western Hemisphere. They balanced respect for the old with fascination for the new.

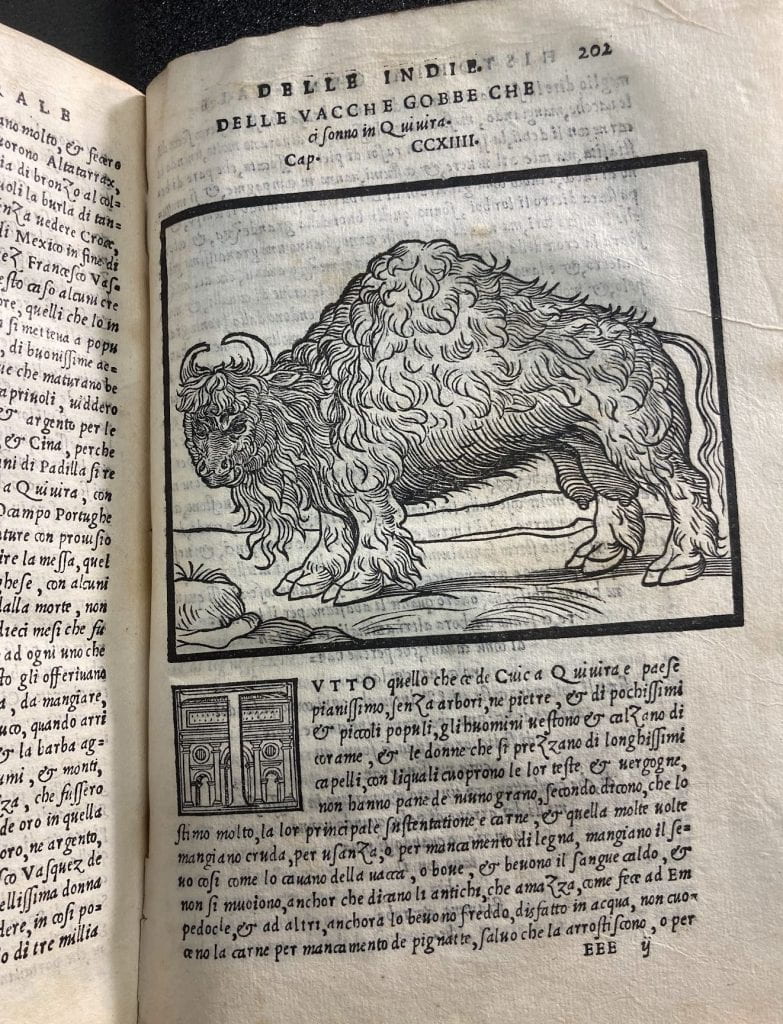

The Tempest has pride of place in the First Folio as the volume’s first play, and it reflects Shakespeare’s engagement with a blossoming international book trade. Prospero, the deposed Duke of Milan, explains to his daughter Miranda that he “to [his] state grew stranger, being transported / And rapt in secret studies” (I.2.76-77). His “library / Was dukedom large enough” (I.2. 109-10), so his brother deposed him. Prospero and his infant daughter were sent into exile and shipwrecked on an island, but he was at least “furnished . . . with volumes that / [he] prize[d] above [his] dukedom” (I.2.166-68). Armed only with his books, Prospero enslaves the island’s inhabitants, the “monstrous” Caliban and spritely Ariel, along with local faeries and spirits. As critics, old and new, have pointed out, The Tempest evinces more than passing familiarity with the classical Liberal Arts, but also fascination with the recent accounts of voyages, discoveries, storms and shipwrecks (Smith 318; Graff and Phelan). The stationers knew there was a market for these. The 1578 Latin translation of Girolamo Benzoni’s Italian New Histories of the New World, is an example from The Texas Collection, as is the Collection’s copy of Richard Hakluyt’s Historie of the West-Indies, published around the same time in London. Among its rare books, The Collection also boasts a lavish folio edition of Hakluyt’s 1599 The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation. The Collection’s 1556 Italian translation of López de Gómara’s General History of the West Indies has what may be the first illustration in Europe of the American bison. The printing press with movable type had only been invented in the fifteenth century, so the sixteenth century witnessed the rapid expansion of the printed book at the same time that Europe was looking outward to the rest of the globe. Two years after the Shakespeare Folio, Samuel Purchas published a four-volume collection in folio, entitled Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas His Pilgrimes. The Texas Collection has a fine first edition set printed in 1625, along with a fourth edition of Purchas’ Pilgrimage from 1626. The title, in full, on the frontispiece of volume I continues: “Containing a History of the World, in Sea Voyages, & Land Travels, by Englishmen & Others, Wherein God’s Wonders in Nature & Providence, the Acts, Arts, Varieties & Vanities of Men, with a World of the World’s Rarities, are by a World of Eyewitness Authors, Related to the World.”

One of the jewels of The Texas Collection is the 1524 Latin translation of Hernán Cortés’s “Second Letter of Relation.” The letter relates the story of Cortés’s conquest of the Aztec empire between 1519 and 1521 in Mexico, which he renamed “New Spain.” Modern readers may take for granted instantaneous access to news from around the globe, but the speed with which word of Cortés’s conquest spread is remarkable given the technology of his day: within a period of months his Spanish letter traveled from the Americas to Spain where it was published in 1522, then only months later translated and printed in Latin. The Nuremberg 1524 edition in The Texas Collection also has the first depiction (outside of Mexico) of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán, present day Mexico City. The temple portrayed at the center displays a grim scene with the Latin label “Templum ubi sacrificant” (the Temple where they sacrifice) and “capita sacrificatorii” to denote the victims’ decapitated heads. We now recognize many of these reports and narratives of conquest as attempts to dehumanize the indigenous Other, to justify the conquistador’s thirst for land and gold. But their greedy descriptions were greedily consumed by Europe’s expanding book market, which in turn spawned a machinery of representation. A 1770 history of the conquest based on the writings of Cortés, also among the Collection’s rare books, has an illustration on the frontispiece’s verso in which the conquistador presents a globe to the Spanish monarch. Cortés is followed by missionaries and soldiers, but also by indigenous peoples, some dressed in animal skins. One in the foreground, particularly dark-skinned, is prostrated with bow, arrow and quiver set aside. A banner with Latin writing over Cortés says “God is with you, Oh strongest of men.” Another banner cites the battle cry of the Israelites against the Midianites from the Latin Vulgate: “The sword of the Lord, and of Gideon!” in the King James (Judges 7: 20). A sun with a triangle (representing the Trinity) spreads its rays over the whole group, but one ray directed at the monarch cites another Latin verse from Judges 6, which in English would be “I brought you forth from their land.” The verse is incomplete but, if we read further into the biblical passage, we find that God is telling the Israelites “I delivered you out of the hands of the Egyptians, and out of the hand of all that oppressed you, and drove them out from before you and gave you their land” (KJV). As far as the Spaniards were concerned, God had delivered a new promised land to them. The 1770 edition was, in fact, annotated by the Archbishop of Mexico: it was meant to give local bishops and priests a primer in the indigenous customs they might encounter in their own parishes.

Cultivating cultural humility at Baylor, we must point out the assumption of cultural superiority in these texts. That should give us pause. Europeans in the Age of Exploration used religion to justify dispossessing a people they considered savage or even demonic. One hundred years after Cortés, and around the time of the First Folio, Samuel Purchas was echoing many of these justifications. Volumes three and four of Purchas His Pilgrimes are particularly interesting for students of Spanish Colonial literature, because they gather some of the earliest English translations of Iberian explorers and historians of Latin America, which in the early seventeenth century included most of the southern portion of what is now the United States. For example, the fourth volume includes an early English translation of Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios, or Shipwrecks, with his sojourn among the indigenous peoples of Florida, Texas, and Northern Mexico. Unlike Cortés, Cabeza de Vaca was abandoned to the North American wilderness, completely at the mercy of the tribes he encountered. Rolena Adorno remarks that “Naufragios reads like an efficiently condensed and straightforward report” (61), but in Purchas’s collection it becomes another tool for demonization of the American Other. Since the pages of the folio edition are so tightly packed with text, he uses running headers and marginal notes to summarize content on each page. But these are often used to moralize, pointing out “ungodly custome” (IV, p. 1512) as when he summarizes a page of Cabeza de Vaca’s account with the header “Indians cured by Christians, Dead Raised, Diabolical Superstition” (IV, p. 1516). At other times he juxtaposes ordinary customs like leatherworking with a casual reference to Satan worship: “Indians slaves to Satan, Leather Habit, Shaving of Skins, Good Food” (IV, p. 1517).

The indigenous point of view, even when it is registered, is always filtered through a European lens: “You taught me language,” says Caliban to his captor, “and my profit on’t / Is I know how to curse” (I.2.366-67). But European representations of the imperial project were not monolithic and we should not assume that Shakespeare approved of the motives or the method of colonization, even as he reflects them in a work like The Tempest. An interesting example of a more nuanced view of European exploration and colonization may be found in the work of El Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. Garcilaso was born in Peru in 1539, the son of an Incan princess and a Spanish captain, and he died in Spain the same year as Shakespeare, 1616. Garcilaso is best known today for his Royal Commentaries of the Incas, originally published in 1609. Extracts were translated into English and published in Purchas His Pilgrimes (see vol IV, pp. 1454-85). The writer paints a more flattering picture of the Inca than previous Spanish chroniclers had, often correcting previous accounts with his superior knowledge of Quechua, his mother’s language. His view of the Spanish conquistadors, published posthumously in his General History of Peru (1617), is uncompromising in portraying their brutality. Garcilaso’s account of the Pizarro brothers’ conquest of the Inca and the civil wars that followed is replete with stories of greed, ambition, and betrayal; fans of Shakespeare’s history plays will find familiar themes there. Volume IV of Purchas His Pilgrimes also has an extract from Garcilaso’s General History of Peru (pp. 1485-89). For a taste of Garcilaso’s prose in the original Spanish, the reader can consult The Texas Collection’s rare second edition of La Florida published in Madrid in 1723. La Florida del Inca, as it is known today, was originally published in 1605 (between the debuts of Shakespeare’s King Lear and Macbeth) and it is a history of the Hernando de Soto expedition to the American southeast, 1539-1543 (Spanish Florida was not just the territory encompassed by the state of Florida today; after de Soto’s expedition it extended from Texas in the West all the way to the east coast, and as far north as Arkansas, Tennessee and the Carolinas). To stitch together his account of the ill-fated expedition, Garcilaso used written reports and oral histories (many of the expedition’s members were also veterans of Peru). But Garcilaso also gives voice to the native Americans, attributing long speeches to their chiefs and warriors. The title page of the 1723 edition references the “heroicos caballeros,” or heroic gentlemen, as being “españoles e indios,” that is, both Spanish and Indian. Nobility, for Garcilaso, was not exclusive to Europeans, it could be shared by the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

IMAGES

FOR FURTHER READING

I’ve included all the books cited above in the REFERENCES, as well as some additional works for the interested reader. For more on the evolution of the book trade in the century and a half after the invention of the printing press, for example, see Lisa Jardine’s chapter “The Triumph of the Book” in her Worldly Goods: A New History of the Renaissance. Spanish Colonial literature is well translated into English, not just in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. See modern translations, for example, of Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios (Castaways), Hernán Cortes’s letters, along with excellent translations of El Inca Garcilaso de la Vega’s works by the Varners and Harold Livermore. Adorno’s short introduction to this literature is an excellent entry to the field. For a historian’s perspective on the Spanish in what is now US territory, see Weber. Greenblatt’s Marvelous Possessions is a new-historicist take on early-modern European representations of the “New” World. The Graff and Phelan edition of The Tempest reprints many articles on the critical controversy surrounding Shakespeare’s engagement with the colonial project in the Americas. Works cited below that are in the Rare Books room of The Texas Collection are followed by RBT.

REFERENCES

Adorno, Rolena. Colonial Latin American Literature: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford UP,

2011.

Benzoni, Girolamo. Historiae novi orbis novae. Geneva, 1578. RBT

Cervantes, Miguel de. Teatro completo. Edited by Florencio Sevilla Arroyo, Penguin

Clásicos, 2016.

Cortés, Hernán. Letters from Mexico. Translated by A.R. Pagden, Grossman Publications,

1971.

—. Praeclara Ferdinādi Cortesii de Nova maris Oceani Hyspania narratio. Nuremberg, 1524.

RBT

—. Historia de Nueva España. México: J.A. de Hogal, 1770. RBT

Fernández Carrión, Miguel Héctor. “Antonio de Solís.” In Diccionario Biográfico

electrónico, Real Academia de la Historia, 2023.

Folger Shakespeare Library. “Read A Shakespeare First Folio.” 2023.

https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeare-in-print/first-folio/bookreader-68/

Graff, Gerald and James Phelan, editors. William Shakespeare’s The Tempest: A Case Study

in Critical Controversy. Bedford / St. Martins, 2000.

Greenblatt, Stephen. Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World. With a new

preface, U of Chicago P, 2017.

—. Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. W.W. Norton, 2004.

—, et al, editors. The Norton Shakespeare: Based on the Oxford Shakespeare. W.W. Norton,

1997.

Hakluyt, Richard. The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the

English Nation. London, 1599. RBT

—. The Historie of the West-Indies. London, n.d. [c1600]. RBT

Jardine, Lisa. Worldly Goods: A New History of the Renaissance. Macmillan, 1996.

KJV = The Bible. King James Version with the Apocrypha. Edited by David Norton,

Cambridge UP / Penguin, 2006.

López de Gómara, Francisco. Historia generale delle Indie occidentali. Rome, 1556. RBT

Mela, Pomponius. Cosmographi geographia. Venice, 1482. RBT

Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Álvar. Castaways: The Narrative of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.

Translated by Frances M. López-Morillas, edited by Enrique Pulpo-Walker, U of California P, 1993.

Ptolemy, Claudius. Geographia. Italian. Venice, 1561. RBT

—. Geographia. Latin. Venice, 1562. RBT

—. Geographia. Italian. Venice, 1598. RBT

Purchas, Samuel. Haklutus Posthumus, or Purchas His Pilgrimes. London, 1625. 4 vols. RBT

Shakespeare, William. Comedies, histories & tragedies, published according to the true

originall copies. London: Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, L. Smithweeke, and W. Aspley, 1623. In “Facsimile Viewer: First Folio (New South Wales),” Internet Shakespeare Editions, University of Victoria, 2023. https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/facsimile/book/SLNSW_F1/index.html

Smith, Emma. This is Shakespeare. Pantheon Books, 2020.

Solís, Antonio de. Historia de la conquista de México. Madrid: Blas Roman, 1776. RBT

—. History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Translated by Thomas Townsend,

London, 1724. RBT

Vega, Garcilaso de la [El Inca]. La Florida del Inca. Madrid, 1723. RBT

—. The Florida of the Inca. Translated by John and Jeanette Varner, U of Texas P, 1996.

—. Royal Commentaries of the Incas and General History of Peru. 2 vols. Translated by Harold

V. Livermore, The U of Texas P, 1966.

Weber, David J. The Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale UP, 1992.

No Comments