Did you know libraries across the country have been working to diversify and add new voices to their collections? In the Arts and Special Collections Research Center we have increased the number of women and Black composers in the collection, as well as composers from international countries. This gives our faculty and students new voices to research and include in performances. In our rare collections we have been systematically adding voices of color and gender to fill in the gaps of the scholarly conversation.

One voice available to you is that of Phillis Wheatley.

Britannica lists Phillis Wheatley as the first black woman poet of note in the United States. In 1761, she arrived in Boston from Senegal as a slave at approximately seven years old. She was named after the family, Wheatley, who bought her and the name of the ship she was transported in, the Phillis. The Wheatley family educated Phillis who showed amazing aptitude for reading and writing. Her first poem was printed when she was only 14 years old. She continued to write with support of the Wheatleys, however her work was continuously criticized and ultimately forgotten during the onset of the Revolutionary War. She died at a young age, 31, due to poor health and living her last few years in poverty.

On the surface this story reads as an interesting colonial story of a successful young woman. But read deeper and you’ll begin to see an extraordinary story of an enslaved girl who played a pivotal role in our nation’s first debates on the rights of men as the formation of independence took hold in the colonies.

For a closer reading of the criticism surrounding Ms. Wheatley, check out Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s book “The Trials of Phillis Wheatley” 2003 (Moody Library PS866 .W5 Z595 2003). In this work, Gates provides background on a dramatic event instigated by Mr. Wheatley. He proposed an interrogation or trial of Ms. Wheatley to prove she was capable of writing. Eighteen prominent men from Boston interrogated her in 1772 to discover whether or not a slave was capable of producing literature. If she proved she could create literature, then abolitionists would have an example to claim equality for all men. She was proven to be capable writer; however, there were still many who would not support a slave moving into their cultural world. Ms. Wheatley was soon forgotten as war broke out against England. Criticism of her writing continued into the 20th century, but not because of her race, rather that her writings were too ‘white’ and she was just imitating those who enslaved her. As Gates summarizes, Wheatley’s accomplishments in the late 18th century were overlooked due to her race. She was too black. And in the 20th century, she is criticized as an ‘imposter’ whose writings are too white. Gates suggests that “the challenge isn’t to read white, or read black; it is to read.”

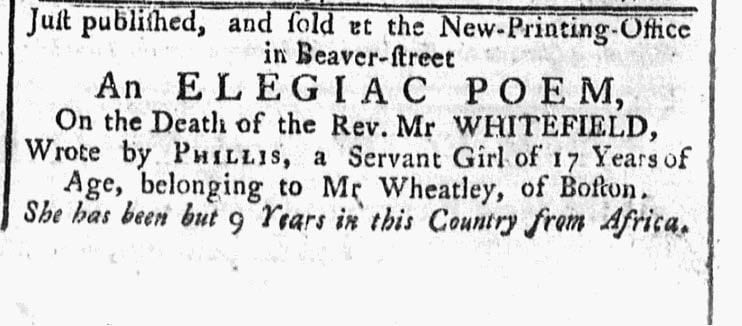

The libraries hold many primary sources for your research in this area including the database America’s historical newspapers where you can find notices of Ms. Wheatley’s publications. Pictured below is an advertisement from October 1770 from the New York Gazette.

The Special Collections in Moody Library hold a rare book by B. B. Thatcher from 1834 entitled “Memoir of Phillis Wheatley : a native African and a slave”. Thatcher offers a supportive and sympathetic review of her poetry and life.

Phillis Wheatley’s extraordinary life offers several pathways for research. We hope you take this time to remember to read deeply.

Let us know if you would like any additional help! www.baylor.edu/library/arts

We look forward to your successful research in these rare voices.