“People don’t realize yet today what we lost when we lost Jim Europe. He was the savior of Negro musicians. He was in a class with Booker T. Washington and Martin Luther King. I met all three of them. Before Europe, Negro musicians were just like wandering minstrels. Play in a saloon and pass the hat and that’s it. Before Jim, they weren’t even supposed to be human beings. Jim Europe changed all that. He made a profession for us out of music. All that we owe to Jim. If only people would realize it.”

– Eubie Blake (quoted in Rose, 60-61).

A little remembered figure today, James Reese Europe was once dubbed the “King of Jazz.” He was a champion for Black music and musicians in the first two decades of the twentieth century, and a key figure in the transition from ragtime to Jazz. Baylor’s Spencer Sheet Music Collection contains twenty Europe publications which together shed light on the development of Europe’s compositional style, business acumen, and on the Black musical community and American musical life during this period. In honor of Black History Month, read below to learn more about Europe’s life and music.

Quick Stats:

James Reese Europe was…

- Founder and first president of the first Black musician’s professional organization in New York (Clef Club, 1910).

- The first conductor to lead an orchestra of Black musicians at Carnegie Hall (“Concert of Negro Music,” 1912).

- The first Black bandleader to receive a major recording contract (1913).

- The first African American officer to lead men under fire during the First World War (March 1918).

James Reese Europe’s Musical Life

Europe was born in 1881 in Mobile, Alabama, but soon moved with his family to Washington D.C., and in 1904, Europe moved to New York to pursue his music career. There he quickly became involved composing popular tunes for Tin Pan Alley and the stage (see his Arizona (1903) held in Baylor’s Spencer Sheet Music Collection here). He also began conducting for Black musical theater productions, a genre that was thriving in the first decade of the century. Most notably, Europe conducted and composed songs for the successful musical-writing team of Bob Cole, John Rosamond Johnson, and James Weldon Johnson. Europe’s song On the Gay Luneta, included in Cole & Johnson’s The Shoo Fly Regiment is part of the Spencer Collection (flip through On the Gay Luneta here). The love song is written for a “Manila Belle” and Europe incorporates a habanera rhythm in the bass line of the verse that contrasts with a syncopated chorus (Riis, 131–32).

While he likely would have found success had he continued to work in musical theater, Europe had different goals. His early career had given him a quick education on the inequities that existed between white and Black working musicians. As a response, Europe and some colleagues founded the Clef Club, a professional organization, booking agency, and union for Black musicians, and Europe was the group’s first President. From the Clef Club’s members, he formed the 125-member Clef Club Symphony Orchestra, which after a successful debut concert at the Manhattan Casino, performed semiannually. On May 2, 1912, Europe arranged for them to play a concert—entitled “Concert of Negro Music”—at Carnegie Hall. This was the first time an orchestra of Black musicians played in the staid music hall, and though the very idea met with resistance, by the time the concert began, the place was “jammed to the very limits of the fire laws with an audience composed about equally of the two races” (The Southern Workman, 163). And the varied program, which included both “classical” and popular syncopated works, was enthusiastically received. In 1913, Europe left the Clef Club to form another organization: the Tempo Club. This club’s goals echoed those of the Clef Club, and similarly, Europe devised groups of varying sizes from its membership to fulfill various performance requests.

Europe met the famed dancing couple, Vernon and Irene Castle, while performing at a private party in the fall of 1913. The pair immediately identified in Europe and his musicians (now often dubbed “Europe’s Society Orchestra”) a superior ability to play syncopated dance music and would almost exclusively call on the group for public performances, new musical compositions, and affiliated recordings until the outbreak of the First World War.

His friendship and collaborations with the Castles boosted him to fame and in December of 1913, Europe’s Society Orchestra was asked to record dance numbers for Victor Talking Machine Company. This was the first time a Black orchestra recorded with a major commercial label. (Hear the band’s recording of Europe’s Castle House Rag here.)

Many of Europe’s compositions during this time show the influence and popularity of the Castles and speak to the couple’s musical preference and dance requirements. We hold several of Europe’s compositions for the Castles in Baylor’s Spencer Collection, including The Castle Walk, Castle Maxixe, Castles’ Half and Half, Castles in Europe, Castle Lame Duck Waltz, Castle House Rag, and Castle Combination, all published in 1914. But Europe and his musicians impacted the Castle’s output in return. Indeed, during a national tour conducting an 18-piece orchestra for the Castles, Europe became the first bandleader to play the first published blues piece, W.C. Handy’s Memphis Blues (to see it in our collection, click here). Much slower than their other dance numbers, Europe suggested the Castles develop a slower dance for Memphis Blues to add contrast to their regular lineup. Though at first hesitant, the Castles created steps to accommodate the slower genre and the fox-trot—a dance that laid the groundwork for many subsequent popular dances and songs—was born.

Over There: Europe in the First World War

On September 18, 1916, Europe enlisted in the 15th New York Infantry, a group of all Black soldiers with (initially) white officers. He told Noble Sissle (who would also enlist) of the motivation for his decision: “There has never been such an organization of Negro men that will bring together all classes of men for a common good. And our race will never amount to anything, politically or economically, in New York or anywhere else unless there are strong organizations of men who stand for something in the community” (Sissle, 36, quoted in Badger, 142). Soon after Europe was commissioned as a first lieutenant, he was asked by Colonel William Hayward to organize the 15th Regimental Band, and the band soon was regarded as one of the best. But Europe’s role was not solely musical—after the regiment was renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment, Europe became the first African American officer to lead the first group of African American soldiers in active warfare in 1918. The 369th’s excellent service record soon earned them notoriety and a new nickname: “The Hellfighters.” During active service, Europe composed several songs he planned to publish after the war. In early June 1918, Europe’s company was attacked with German poison gas bombs and Europe was evacuated to a small field hospital. When Sissle visited him there, “[Europe] looked up through his big, shell-rimmed glasses…a big broad smile swept over his face…the first thing that he spoke up and said was: ‘Gee, I am glad to see you boys! Sissle, here’s a wonderful idea for a song that just came to me, in fact, it was [from the] experience that I had last night during the bombardment that nearly knocked me out’” (Sissle, 169, quoted in Badger, 187).

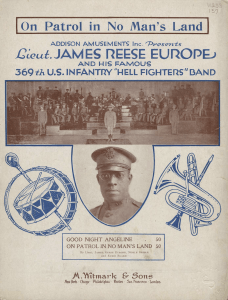

The song, held in our collection, was On Patrol in No Man’s Land (view it here). The song recreates the sound of the battlefield for audiences back home, with “instruments imitating explosions, rat-tat-tat machine guns, wailing sirens, and whistling shells” (Brooks, 282).

In August of 1918, the 369th Regimental Band performed a concert at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées and afterward toured the various camps and hospitals in the area. Following this, every concert they gave was met with overwhelming enthusiasm. Though Europe himself recognized the 369th wasn’t the best band touring at the time, their playing was distinct in ways that became intimately tied to a word just emerging in the fall of 1918: Jazz. Indeed, though many French were being exposed to Jazz through the 1917 recordings of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, the 369th is credited with igniting the Jazz craze in France and Britain. Charles Welton, in a 1919 New York World article, wrote, “this band operated with B-flat trombones or machine guns, just as it happened, all the way from Brest to Armistice. It cleaned up everywhere. It filled France full of Jazz” (Welton, 7, quoted in Badger, 196). Though at first an amorphous term, Europe’s own definition was that Jazz is something performers do to music during performance (Badger, 195).

Upon their return to New York, the now famous members of the 369th were celebrated in a parade down Fifth Avenue, and, wanting to capitalize on their publicity and help revitalize the depleted wartime presence of Black musicians and music, Europe kicked off a ten-week tour of the Regimental Band with a concert at Carnegie Hall on March 16, 1919. Sissle marveled that the “temple of classical music” was filled with Jazz (Brooks, 284). And throughout the successful tour, reviews of the band’s performances praised not only the band’s performances but also the strength of its leader. The band recorded with Pathé Record Company in four recording sessions in the Spring of 1919 (hear the band’s recording of On Patrol in No Man’s Land here). While they played many of the same pieces Europe had led before the war, both the group’s instrumentation, playing style, and emphasis on blues/fox-trot were now identified with this new term, Jazz. And these features of the band’s performances were important ingredients for the Jazz that emerged in the 1920s. Of greater importance though was the way in which the band’s performances seemed to change many audience member’s perceptions of Black musicians—and people—generally. In a Chicago Defender article following a Hellfighters concert on May 3rd, the author wrote: “The most prejudiced enemy of our Race could not sit through an evening with Europe without coming away with a changed viewpoint” (“Jazzing Away Prejudice,” 20).

Now at the pinnacle of his career, Europe began making plans for him, Sissle, and Blake to start a new National Negro Symphony Orchestra and a new musical production to revitalize Black musical theater. But, during the intermission of the 369th’s return engagement to Boston on May 9, 1919, percussionist Herbert Wright, apparently upset by what he deemed unfair treatment from Europe, stabbed Europe in his dressing room in front of Sissle and several other witnesses. Europe was able to arrange for assistant conductor Felix Weir to finish the concert and make plans to meet the group in the morning for a scheduled engagement for Governor Coolidge. Sissle and several others went to the hospital after the concert, but shockingly just a few minutes after they arrived, Lieutenant James Reese Europe died at the age of 38.

The Lost “Savior of Negro Musicians”

At the time of his death, Europe was regarded as one of the best conductors, the leading champion of Black musicians, and “The Jazz King.” While it’s impossible to know what his career would have looked like had he lived, he would undoubtedly have continued to work for increased opportunities for Black musicians. In 1914, he pointed out in a Tribune interview that Black composers received 1/12 to 1/6 of the royalty payments accorded white composers, even when their works were in higher demand. He said “I have done my best to put a stop to this discrimination, but I have found that it was no use…. I am not bitter about it, it is, after all, but a slight portion of the price my race must pay in its at times almost hopeless fight for a place in the sun. Someday it will be different and justice will prevail” (New York Tribune (1914), Quoted in Badger, 121).

And, his biographer Reid Badger muses, had he lived, Europe would have not only been a transitional figure, but a leading figure in the Jazz Age. This is undoubtedly true, and he would have continued to work toward the development and promotion of Black music more generally. Europe spent much of his career navigating the line between the realms of popular and classical music – a line that many at the time thought imperviable. In line with the writings of W.E.B. Du Bois, Europe believed that what mattered more than music’s perceived refinement (or lack thereof) was its authenticity to Black life and experience. In an Evening Post interview in 1914, Europe said that African Americans “have our own music that is part of us.” “It’s us; it’s the product of our souls; it’s been created by the sufferings and miseries of our race.” Whether accompanying the social dancing of the Castles with a ragtime tune, conducting the pit orchestra for a Cole & Johnson musical, “Jazzing” a march tune with the 369th, or programming works by Will Marion Cook or Harry T. Burleigh at Carnegie Hall—what’s most important is that the music “breathes the spirit of a race” (Evening Post (1914), quoted in Kimball & Bolcom, 60-61).

Baylor Libraries encourage you to continue your research on these hidden stories of amazing people well beyond the named month for Black history. The songs in this post came from the Baylor Libraries’ Spencer Collection of American Popular Sheet Music. If you are interested in viewing these songs in person, reach out to RareCollections@baylor.edu.

For Teachers: Two Sample Teaching Activities

Below are sample teaching activities related to the James Reese Europe materials in the Spencer Collection that you might adapt for your classes. If you’re interested in planning a class visit to the Arts & Special Collections Reading Room, please reach out to: RareCollections@baylor.edu.

Teaching Activity 1 (Non-Music Majors or Lower-Level Music Majors):

Students come into class with no prior knowledge of James Reese Europe.

- They are given a short introductory lecture (can also be pre-work) about the intersections between the genres of Tin Pan Alley, Vaudeville, and Musical Theatre, and the styles of Ragtime & Blues in the early decades of the twentieth century. They are introduced to the day’s activity and told that all the songs presented today were composed by James Reese Europe.

- Several Europe songs spanning his career are presented chronologically along with QR codes to recordings of each piece. Students are given a worksheet that will ask them to:

- Observe the pieces visually: take note of the cover image, the individuals or institutions mentioned, and the date. Also note anything interesting or unfamiliar, and predict: how do you think this piece sounds?

- Listen to the recording and consider the musical style: what instruments/voices do you hear? How would you describe the music and its style? Is this what you thought this might sound like when observing the score visually? Is this like any music you know or have studied in this class? If this were part of the soundtrack to a film, what would be happening in this scene?

- Reflect on these observations: What do you think the purpose of this song is? Who do you think it was written to appeal to? What values or opinions does it highlight? Does it relate to anything you know about what was going on in history at this time?

- Pair up and share your observations and reflections with a partner. Then together, use the pieces as evidence to write a backstory for the composer of these works.

- The class ends with pairs sharing their backstories with the rest of the class.

- Professors can then either assign this blog post for the next class period, or address Europe in their next lecture.

Teaching Activity 2 (Upper-Level Majors)

Students come into class having already learned about James Reese Europe, or having read this blog post and/or other biographical materials.

- Several Europe songs spanning his career are presented chronologically along with QR codes to recordings of each piece. Students are introduced to the day’s activity and given an overview of the songs presented. Students are given a worksheet that will ask them to:

- First, observe the extramusical material: the cover image, the individuals or institutions mentioned, the date, publisher, and note anything interesting or unfamiliar.

- Observe the music & listen to the recording

- Describe the: instrumentation, genre, and style.

- How does the recording relate to the score? What’s the same? What’s different?

- Name another piece(s) or composer that this piece is similar to. What about it makes it like that piece? What makes it different?

- Reflect:

- Why do you think the composer wrote this piece?

- Who was the intended audience?

- What values or opinions does it highlight?

- Does it relate to anything you know about what was going on in history at this time?

- How does the music itself relate to the composer’s intentions, the intended audience, or the social or historical context?

- Imagine you are writing a scholarly article about James Reese Europe, using these pieces as evidence. Write a thesis statement for that article. (For instance, using your previous answers, your thesis might relate Europe’s music to Jazz, ragtime, musical theater, social dancing, or the development of Black music in the early 20th century. Or it might relate the music to the social or historical context, or to the composer’s motivations and audience.) Which pieces of sheet music viewed today will you use to support that thesis?

- Pair up and share your thesis statement and which pieces of sheet music you believe will support your thesis. Then discuss with your partner: aside from those pieces, what other kinds of evidence will each of you need to support your thesis? Note the type of evidence you come up with here.

- At the end of the session, students are asked to share their thesis statements and aspects of their paired discussion with the rest of the class.

Sources & Further Reading

Adams, Elbridge L. “The Negro Music School Settlement,” in The Southern Workman 44 (1916), 161-165.

Badger, Reid. A Life in Ragtime: A Biography of James Reese Europe. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Brooks, Tim. “James Reese Europe” In Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919. University of Illinois Press, 2004. Pp. 267-292.

EDSITEment!: African-American Soldiers in World War I: The 92nd and 93rd Divisions. National Endowment for the Humanities.

Harris, Stephen L. Harlem’s Hell Fighters: The African-American 369th Infantry in World War I. Brassey’s, Inc., 2003.

Herd, Ronald. James Reese Europe: Jazz Lieutenant. BookSurge Publishing, 2005.

“Jazzing Away Prejudice,” in the Chicago Defender, May 10, 1919, 20.

Kimball, Robert & William Bolcom. Reminiscing with Sissle & Blake. Viking, 1973.

Library of Congress, “James Reese Europe, 1881-1919”

Riis, Thomas. Just Before Jazz. Smithsonian, 1994.

Rose, Al. Eubie Blake. Schirmer Reference, 1979.

Sissle, Noble. “Memoirs of Lieutenant Jim Europe.” Unpublished manuscript, 1942.

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History (3rd ed.). Norton, 1997.

Teaching with Documents: Photographs of the 369th Infantry and African Americans during World War I

Thompson, Donald; Moreno de Schwartz, Martha. James Reese Europe’s Hellfighters Band and the Puerto Rican Connection. Parcha Press, 2008.

Welton, Charles. “Filling France Full of Jazz.” New York World, 1919.

this is fabulous, Bethany! thanks for all the work pulling this together and sharing it!

Thank you so much for posted this. Not many people know or talk about James Reese Europe and I’m doing a presentation on him today for seniors. I thought this article was the best I’ve ever read on Europe. Very well done!