This blog post was written by Graduate Assistant Mikah Sauskojus, master’s student in History.

The legislative career of Don Adams coincided with several substantial events in Texas’s political history, but few had the same national ramifications as the fight over the codification of equal rights in both state and federal law. During the 1970s, Adams supported both the federal and state Equal Rights Amendments in the legislature. However, in 1974 and 1975, coordinated efforts to undermine Texas’s support for the ERA began agitating for Texas to follow in the footsteps of the four states that had rescinded their previous ratification of the federal amendment. As a state senator, Adams was a target for political correspondence on both sides of the issue, but his response to the controversy indicates his commitment to representing his district first and foremost.

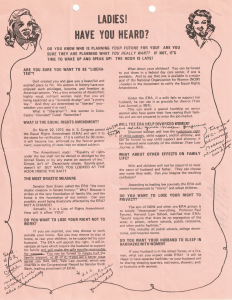

The passage of the Texas Equal Rights Amendment in the legislature sent the issue out to the counties for approval. After the state amendment’s passage during the election of 1972 and the legislature’s passage of the federal ERA, the issue went dormant for several years, as other states either ratified or rejected the amendment. In 1974, two different Texas-based groups, Women Who Want to be Women (WWWW, Fort Worth) and the Committee to Restore Women’s Rights (San Antonio) began marshaling resistance against both forms of the ERA through grassroots and legislative campaigns. The efforts of these groups led hundreds of concerned citizens in Adams’s district to write him letters pleading for the ERA to be rescinded. While these letters frequently carry a distinctly religious bent of the ERA opposition under figures like Phyllis Schlafly, they are also grounded in practical logistical concerns about legal protections for women. The WWWW’s primary pamphlet, to which many of the letters to Adams refer, compares life under the ERA to the “liberated” state of Cuba under Castro and makes sweeping (and often erroneous) statements about the rights women would lose under the new ERA (Adams made several corrections or notes regarding the more egregious errors in one copy of the document, such as its language surrounding child custody rights during divorce).

In response to these letter writing campaigns, Adams maintained a respectful attitude that honored the opinions of his constituents while also acknowledging their relative minority among the people he represented. In one letter explaining his position, Adams noted that the materials produced by the WWWW were “irrational, emotional, and in most respects incorrect,” and explained that he had attempted to correspond with the organization itself to clarify its statements. Their lack of a response, combined with the overwhelming 4 to 1 margin of support for the Texas ERA in his senate district, made him disinclined to support a move to repeal an amendment that simply codified protections already provided by Supreme Court case law. While he treated the anti-ERA position as a minority that should not be allowed to advance its legal agenda, he still worked to find a balance between respecting the majority of his district and the personal concerns of his individual constituents.