Like most people, I always thought that the black bird was just a figment of a mystery writer’s over-active imagination. Granted Bogart’s portrayal of Sam Spade is one of the great acting jobs of the hard-boiled film noire genre coming out of Hollywood in the 1940’s, but it was all fiction, or at least that’s what I thought. The writers of the movie suggested that the falcon was a gift from the Knights of Malta to Spain’s king, Carlos V. While doing some research at the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid in the mid-1980’s, I was reading Andreas Schott’s Hispania Ilustrata (1604), and although there was nothing too unusual about that, I came across a strange footnote that referred to a London publication of 1544 by Theodore Poelmann which made an indirect reference to the Arabic Spaniard Ibn Ben al Godón’s travelogue entitled, أسود الطيور. In that travelogue El Cordobés, as he was nicknamed by his fellow travelers, discusses the will and the final disbursement of the personal effects of Jacques de Molay, the last Templar Grand Master. This too-good-to-be-true footnote, which also spoke of a piece of the true cross of Jesus Christ, suggested that among those objects listed in the will was a black-enameled falcon. A copy of the will was supposed to be in a 1499 publication from Valencia by the German printer Juan Párix, Historia universal de los Templarios en la península. I had heard of Párix, but a search of card catalogues (including WorldCat) across the world did not turn up a single reference to this book. Even a few shady sources hinted that the book never existed. It suggested to me that the title was apocryphal, or that the publisher or the title were wrong–maybe the publication date or place were incorrect as well. I let it go. Searching for lost objects or buried treasure was for souls much more adventurous than mine, so I filed my notes and continued my research of medieval necromancy. About a year later, after drinking too much and fighting with someone, I stumbled into an antique shop that specialized in old volumes, incunabula, rare manuscripts, palimpsests, and the like, looking for an illuminated piece of mediavalia that I could frame and hang in my livingroom. I saw Párix’s name long before I realized that this was the book for which I had been looking for more than a year. There were no page numbers, but in an appendix at the end of the book was a copy of Molay’s will with the list of his personal effects. Though the list was rather mundane–a house, horses, dishes–there was an “auem nigri.” It was to be handed over to the Knights Hospitallers. I left the book where it was since I couldn’t afford the fancy price tag, but I never forgot about it. When I went back to buy the book a number of years later, the shop was closed and empty. Several years later, while having lunch with a Spanish history professor in Segovia, he mentioned the black bird as a gift from the Knights of Malta to Spain’s king, Carlos V for services rendered. Yet, neither he nor I could connect the one black bird with the other with almost two hundred years between the death of Molay and the gift to the king. My friend, who writes on the history of law in Spain and the Templars, reminded me that the bird never made it to Madrid, probably hijacked off of the coast of Sicily. The ship that would have carried it to Valencia never made it into to port, vanishing with all hands in 1554. All of this suggests a larger mystery of what happened to the “auem nigri,” but in spite of what the movie might suggest, the bird has never turned up and may lie at the bottom of the Mediterranean ocean. Perhaps the writers found reality stranger than fiction, thinking that no one would believe them anyway.

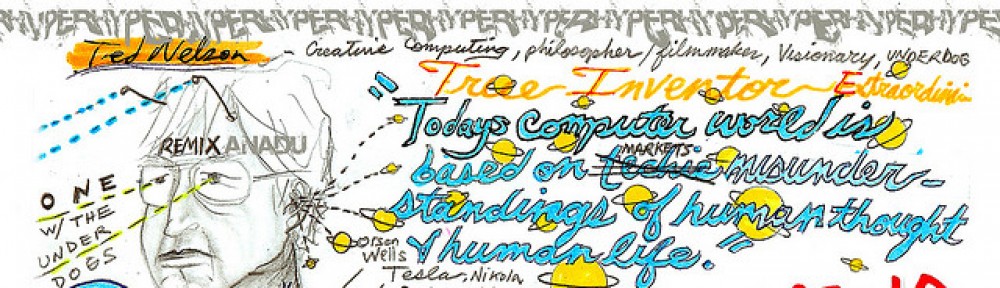

New Media Seminar – Spring 2012

Awakening the Digital Imagination