By Chelsea Cichocki

In the early 1900s, women were gaining greater access to education across the country through the creation of normal schools and women’s colleges (Thelin, 2011). Baylor University, in particular, was ahead of most institutions in its time, having created a co-educational learning environment fifteen years prior (The Baylor Bulletin, 1900-01, 4, 4). Men and women could enroll in the same courses and attend chapel together (The Baylor Bulletin, 1900-01, 4, 4) as well as meet together at soirees and literary debates (The Lariat, 1910, February 25), which affirmed the tradition of co-education at Baylor.

Early articles from Baylor University’s student newspaper, The Lariat, between 1900 and 1920 included overt mentions of advocacy for women. In 1901, an early feminist poem, “A College Girl of the Period” was included in the university’s newspaper, with the author describing an extraordinary and well-rounded female student of the time.

Translates a Latin ode; wins when prizes are bestowed / For which college men are striving by the score; … So, in spite of Dr. Clark, she is rising like a lark, / And in realms of erudition she does soar; / In the future, who can say, that she will not get fair play, / And will have opened to her every college door? (The Lariat, 1901, September 21, p. 3)

Women’s access to education at Baylor University was additionally salient due to the teaching efforts and visions of Dorothy Scarborough and John S. Tanner. In her novel, Bess Whitehead Scott (1989) praises Scarborough for her enthusiasm, nurturance, and advocacy for her female students, as she persistently encouraged her female students to contribute to creative writing compilations (Scott, 1989, p. 60). In Tanner’s speaking notes, one can find his vision for women’s education at Baylor University, including preparations for vocations, motherhood, and social life (The Baylor Bulletin, 1900-01, 4, 5, p. 71).

The feminist literature, coupled with advocacy from faculty members during the time, are ideal when considered on their own. However, although women were granted greater access to education at Baylor than at other institutions between 1900 and 1920, women were still constrained due to the unequal treatment of the sexes in housing, financial access, and educational opportunities, as a result of pressures from an ever-present male-focused society.

Women’s Access to Housing

Evidence from Baylor University’s bulletins and catalogues illustrates the housing available to their female students in Burleson Hall: “Young ladies boarding in it have the advantage of better accommodations than can be had elsewhere at the same rates” (The Baylor Bulletin, 1904-05, 8, 3, p. 149). The housing for female students was, expectedly, separate from male students (The Baylor Bulletin, 1904-05, 8, 3) but they were not treated equally. Women were often crowded in the dormitories and did not receive the comforts and luxuries that they had been previously promised (The Lariat, 1919, November 6, p. 6). Males at the time had more than one residence hall (The Baylor Bulletin, 1904-05, 8, 3), which suggests that the female students were not as accommodated as males, despite the proclamations of progressiveness through co-education.

Women were initially allowed to live away from the university, with family members or with a professor’s family (The Baylor Bulletin, 1900-01, 4, 4). However, President Samuel Palmer Brooks wrote a letter to the parents of the female students attending Baylor University in 1907: “Last year certain young ladies took rooms in private homes after the dormitory was filled. Some of them abused the privileges….engagements of rooms will not be made in private homes” (The Lariat, 1907, July 27, p. 3). Women were only allowed, under extenuating circumstances, to live with nearby family members at this time (The Lariat, 1907, July 27, p. 3). If the female students did not have substantial funds to accommodate the housing costs to live in Burleson Hall, they would need to either find employment or not attend Baylor University.

Women were limited access to education at Baylor University because of these housing concerns: the lack of proper accommodations, the discomfort, and the potential absence of funds necessary to afford campus housing. Although women were granted some luxuries in housing, such as heat and a dining hall (The Baylor Bulletin, 1900-01, 4, 4, p. 73), they were not treated as men were: women were more closely monitored and prohibited from traveling alone. Women in the early 1900s at Baylor University constituted approximately 40% of the student body (The Baylor Bulletin, 1904-05, 9, 3); given this information, it would be expected that greater accommodations would be made for female students. Ensuring comfort and more autonomy during this period could have provided better access to women at Baylor University.

Financial Access

Women were encouraged to attend Baylor University to have a well-rounded experience. One man wrote an article for The Lariat in 1910 describing the reasons he sent his daughter to college: for himself, for his daughter’s personal development, for the benefit of others, and for her to use her God-given talents (The Lariat, 1910, September 3, p. 1). This man explained that he had set up a college fund for her in her early life so that she could have the same opportunity as her brothers (The Lariat, 1910, September 3). By having these funds in place through their families, women were able to have access to education.

However, many women were not so fortunate to have money designated for higher education. Women were provided the option to work through college for the purpose of paying for their own education. Jewell Legett, a student at Baylor University in 1906, described the jobs that women held, including sewing, serving in the dining halls, crafting, selling books for the school, and serving wealthier young women in their dormitories (Legett, 1906). Although women were fortunate to pursue their education and work at the same time, Legett continues to say: “This girl made her tuition last summer by giving guitar lessons. Plucky isn’t she? And she is healthy and happy as one could wish to see, yet she has her hands full” (Legett, 1906, p. 1).

If a woman needed to, or chose to, work through college, her schedule and personal life needed to be adjusted accordingly (Legett, 1906). With the added responsibility of paying for their education, working college women not only had less time to focus on their studies, but they also had little free time for participation in organizations at Baylor University.

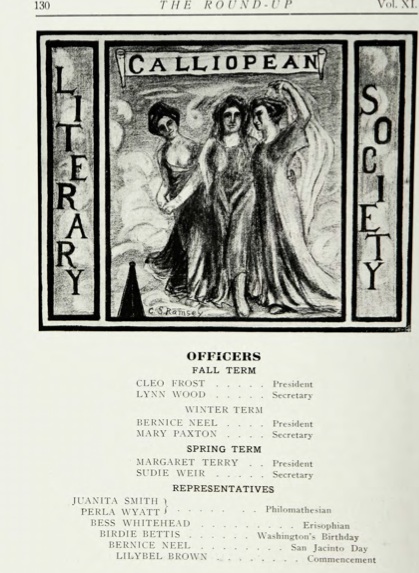

Scholarship Opportunities through Literary Societies

The Calliopean Literary Society and the Rufus C. Burleson (RCB) Society were two opportunities for women to be educated outside of the classroom between 1900 and 1920 (The Lariat, 1918, August 8). Rufus C. Burleson himself started the Calliopean Literary Society for women, so that they could measure up to the activities in which men were participating (The Lariat, 1918, August 8). The women in these societies competed in literary debates, performed in plays and concerts, collaborated with one another, and planned events with other women, men, and faculty members at Baylor University, thereby enriching their collegiate experiences (Scott, 1989).

Beginning in 1904, membership with the Calliopeans and RCBs provided scholarship opportunities for the women who won debates (The Baylor Bulletin, 1906), showing the growing interest in women’s access to education. However, membership in these literary societies was a vast commitment; in her novel, Bess Whitehead Scott (1989) describes the intricate planning that accompanied the Calliopean experience — writing, production, rehearsal, and performance — which often conflicted with women’s academic schedules. Women who already had time constraints and financial stressors with their jobs were likely unable to commit, but they were caught in a bind: they had enough on their plates with pursuing education and employment, but membership with the Calliopeans could provide them with exclusive opportunities to secure scholarship funds that might keep them at Baylor University without excessive employment deterring from their studies.

Educational Opportunities for Women

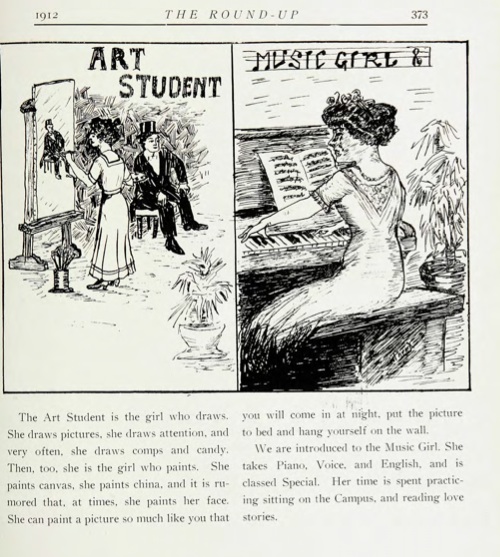

Since 1886, women have been permitted full enrollment at Baylor University (The Baylor Bulletin, 1904-05, 8, 3), which allowed them to move from Baylor Female College to the co-educational university. Between 1900 and 1920 women were consistently enrolled at Baylor University, but many were enrolled as special students, meaning that they were enrolled in courses without intentions of graduation or pursuit of a degree (The Baylor Bulletin, 1906, 9, 3). Of 133 special students in the 1905-1906 calendar year, 129 were women (The Baylor Bulletin, 1905-06). Although women were typically allowed to enroll in classes of their preferences, newspaper articles from Baylor University suggest that domestic science and fine arts tracks were targeted at female students.

“Most every young man is within reach of some institution which exists for the purpose of teaching him his life’s work, to which women are not barred except by the decree of ages that her most useful service is in the home. She should be trained for that service” (The Lariat, 1913, April 25, p. 2).

In 1915, after a group of young women successfully prepared a meal for a large audience, professors at Baylor University continued in encouraging the development of domestic science; one professor called it “the finest of fine arts, the art of homemaking” (The Lariat, 1915, March 4, p. 1). Although Baylor University was ahead of many other American institutions between 1900 and 1920 by allowing men and women to take the same classes, women were still “confined to the academic kitchen” (Thelin, 2011, p. 143).

President Samuel Palmer Brooks addressed the Waco Equal Suffrage Association in 1914 as an advocate for women’s suffrage. Although he stated that men and women should be treated equally, the underlying message in his speech seems to be that women should be present on college campuses, but with limits. Brooks (1914) wrote, “The educated women thinks not less of art and flowers, but also of pure food, city and home sanitation” (p. 8). Although he espoused co-education, Brooks, like most of society, seems to have preferred women to pursue the disciplines that would keep them in traditional roles.

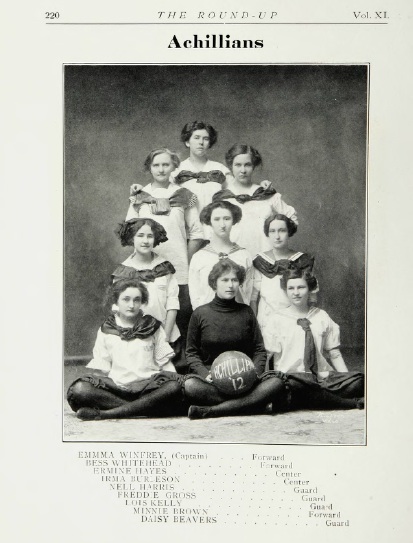

Although photographs in Baylor’s annual yearbook, The Roundup, promote a large athletic program for female students at Baylor University during this time, Bess Whitehead Scott’s (1989) personal account expresses a different view, suggesting that males and females had different standards: “I missed the competitive sports I had enjoyed at Baylor Female College. In the university, the girls had only gym classes, and seniors were excused from these. We posed in fake tennis and basketball pictures for the yearbook” (Scott, 1989, p. 61). Although men and women took classes together, they did not meet much outside of the classroom, with the exception of literary debates and soirees, which were described as “the visible symbol of co-education” (The Lariat, 1910, February 25, p. 2). In the commentary of one issue of The Lariat, an individual wrote: “Co-education is a fine thing, but don’t try to push it beyond co-recitation yet awhile” (The Lariat, 1905, September 13, p. 4).

Societal Constraints

Women at Baylor University between 1900 and 1920 were enabled greater access than at other institutions, but they were still constrained due to the societal expectations and norms present on campus. On the societal level, women’s primary responsibilities were to tend to the home and children; so when more women began attending college, they were encouraged to be kept “in their sphere” and separate from male students, even at co-educational institutions such as Baylor University.

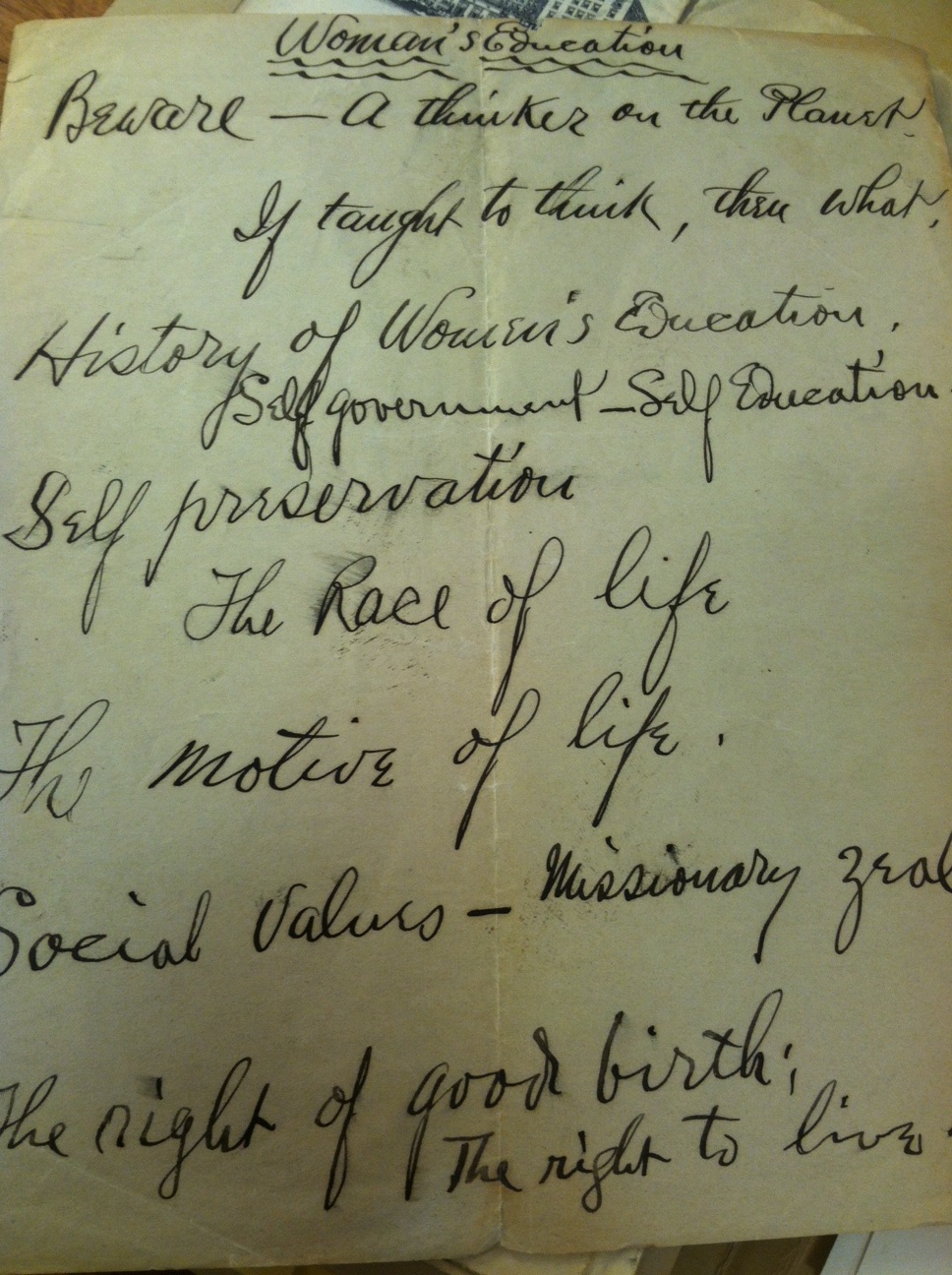

Before this era, the general worry was that college would harm women. However, with the growing presence of women on college campuses between 1900 and 1920, the new fear was that women’s education would threaten men (Thelin, 2011). One of President Brooks’ personal notes regarding women’s education at Baylor University echoed this concern: “Woman’s Education / Beware — A thinker on the Planet, if taught to think, then what” (Brooks, n.d.).

This is not co-education. This is hardly the shadow of it…. Instead there is a spirit that the boys and girls must be separated in church, in school, in chapel; in fact, in everything. It is nearly assured that they should be separated forever. Is Baylor a penitentiary, that we should be so kept apart? (The Lariat, 1916, March 16, p. 2).

The following week, The Lariat published a rebuttal to the criticism; however, the columnist only addressed the criticism of President Brooks and another minor argument posed in the week prior (The Lariat, 1916, March 23, p. 2). Women’s access to education and all matters related to co-education were ignored in the response.

Women’s Suffrage

In the first two decades of the 20th century, the women’s suffrage movement was escalating. Before women were granted the right to vote, the debate about women’s suffrage ensued at Baylor University. Although President Brooks supported women’s right to vote (Brooks, 1914), the females of the 1913 class at Baylor University were typically indifferent about women’s suffrage (The Lariat, 1913, February 8). In one edition of The Lariat, a journalist wrote, “‘I don’t want to vote.’ This is the sentiment of the majority of the young ladies of the senior class of Baylor…None of the young ladies seem to be militant or ever active suffragettes” (The Lariat, 1913, February 8, p.1). Some women expressed beliefs that elections should only be for men, and if they were interested in a particular issue, they should have their husbands vote on that matter for them (The Lariat, 1913, February 8, p. 1).

Focus on Males

Coinciding with the culture of the United States between 1900 and 1920, Baylor men were at the forefront, even when women’s access to education was being discussed. For example, the male literary societies debated about women’s access to education at Baylor University: “Resolved, That co-education is non-beneficial to the students” (The Lariat, 1920, April 1, p. 4). Although a column about co-education’s benefits for the university included hopes for women to learn etiquette and to experience social interaction in their learning experiences, the focus is on the male students: “The quickest way for a man to develop social polish and grace is to know the refining influence of woman” (The Lariat, 1919, November 6, p. 6).

In general, women seemed to have internalized, and accepted, the societal view that they were inferior in this time. Even when female students published an issue of The Lariat in 1915, with the subtitle “Co-Education All the Way,” the emphasized benefits of co-education were homemaking and marriage rates for female Baylor alumnae (The Lariat, 1915, March 4, p. 1). In collegiate environments, as a whole, women were considered “second-class citizens in the campus community” (Thelin, 2011, p. 183). The culture of the time in the United States was one focused on males, and Baylor University was no exception to this rule.

Conclusion

Although women may have benefited from the co-educational experience at Baylor University between 1900 and 1920, they were not seen as equal to their male counterparts. Despite being provided with access to education in the classroom and chapel, women at Baylor University faced constraints in housing, finances, and educational opportunities due to society’s expectations for women during this time. Women may have been able to advocate for themselves on campus, but they were still up against a society that was focused on developing men. Although administrators and professors expressed their concerns and appreciation for women’s access to higher education, the campus atmosphere at Baylor University still matched much of the rest of the United States’: with more options and potential for growth available for male students.

References

The Baylor Bulletin (1900-01). The Texas Collection at the Carroll Library, 4(4), Waco, TX: Baylor University.

The Baylor Bulletin (1900-01). The Texas Collection at the Carroll Library, 4(5), p. 71, Waco, TX: Baylor University.

The Baylor Bulletin (1904-05). The Texas Collection at the Carroll Library, 8(3), Waco, TX: Baylor University

The Baylor Bulletin (1906). The Texas Collection at the Carroll Library, 9(3), Waco, TX: Baylor University

Baylor University (1901, September 21). A college girl of the period. The Lariat, p. 3.

Baylor University (1905, September 13). Co-education is a fine thing… The Lariat, p. 4.

Baylor University (1910, February 25). Baylor’s legends. The Lariat, p. 2.

Baylor University (1910, September 3). Why I sent my daughter to college. The Lariat, p. 1.

Baylor University (1913, Feburary 8). Senior co-eds talk on suffrage: Young ladies of the thirteen class give their views on voting. The Lariat, p. 1.

Baylor University (1913, April 25). Domestic science. The Lariat, p. 2.

Baylor University (1915, March 4). Baylor co-eds act as cooks, waitresses, dishwashers and prepare record meal for 300. The Lariat, pp. 1-3.

Baylor University (1915, March 4). Baylor’s girl grads rank high in number homemakers. The Lariat, p. 1.

Baylor University (1916, March 16). Hypocrisy in Baylor? The Lariat, p. 2.

Baylor University (1916, March 23). [No title.] The Lariat, p. 2.

Baylor University (1918, August 8). The Calliopean literary society. The Lariat, p. 1.

Baylor University (1919, November 6). Co-education: It’s [sic] value and benefit to the city. The Lariat, p. 6.

Baylor University (1920, April 1). Erisophians have good prospects this term. The Lariat, p. 4.

Brooks, S.P. (n.d.). Woman’s education. [Note on education]. The Texas Collection at the Carroll Library (Samuel Palmer Brooks Vertical File Folder, 2C57-55), Waco, TX.

Brooks, S.P. (1907, July 27). To parents. The Lariat, p. 3.

Brooks, S.P. (1914, April 30). Some phases of woman’ suffrage. [Speech]. The Texas Collection at the Carroll Library (Samuel Palmer Brooks Vertical File Folder, 2C61-108), Waco, TX.

Legett, J. (1906). How a girl can make her way through college. The Lariat, pp. 1-2.

Scott, B.W. (1989). You meet such interesting people. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

Thelin, J.R. (2011). A history of American higher education (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.