I’ve been a Malcolm Brogdon fan from the time he was drafted in 2016. My reasons were simple. I liked his game, but more importantly, I liked his college major: history.

Some people root for particular styles of play or for the home team. I root for the humanities.

Brogdon has long spoken up about issues related to racism and social justice. Still, he’s had a new level of urgency in the past two weeks. He joined Jaylen Brown on the ground in Atlanta to participate in demonstrations, and subsequently gave an interview to NBA.com where he discussed his reasons and motivations for stepping up his activism. Last Friday he also penned an op-ed for USA Today.

“My grandfather was a giant walking amongst men. He was involved in the Civil Rights movement, strategizing, demonstrating, organizing. It’s the only way to make change.”

Malcolm Brogdon of the @Pacers on #NBATogether with Ernie Johnson. #NBAVoices pic.twitter.com/91KmIjhwpx

— NBA (@NBA) June 4, 2020

Brogdon framed his motivations in terms of history, including his own personal history. He discussed his grandfather, John Hurst Adams, describing him as a contemporary of Martin Luther King, Jr. and a “giant walking amongst men” during the height of the civil rights movement in the 1960s.

“I grew up with that in my blood,” Brogdon said in his NBA.com interview. “I grew up with my grandparents, understanding that the only way to change policy, the only way to make real change in this country, is to demonstrate, is to push your agenda, is to be demanding, is to not give up.”

Brogdon said something else that caught my attention. He mentioned that his grandfather was an African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) Bishop for over twenty years and that he was involved in the civil rights struggle in Waco, Texas, and Seattle.

Studying the intersection of faith and sports is what I do, and I do it while at a university in Waco, Texas. I knew that I had to do some research on this.

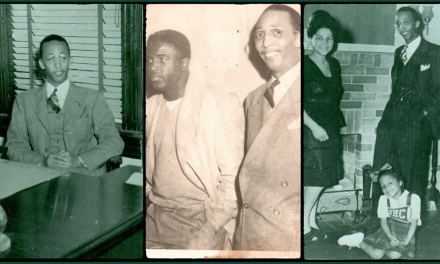

People well versed in civil rights history or the history of the Black church in America probably know of John Hurst Adams already. The basic outline of his life is widely available online at places like BlackPast. And he was important enough to be included in The History Makers, a collection of oral history interviews with African American leaders—as was his wife Dolly Desselle Adams , a partner in his activism and a prominent leader in her own right. The two had three children, including Dr. Jann Adams, Malcolm Brogdon’s mother.

What I want to do here is to dig deeper beneath John Hurst Adams’ list of accomplishments. What ideas and philosophies did he articulate? What was his connection to sports and to Waco? What can we learn from his life and work today?

Faith and Sports

Born in 1927, Adams grew up in South Carolina, the son of an AME minister. Involvement in church was obviously central to his childhood. So was civil rights activism. Even in the Deep South, Adams recalled witnessing his father work to challenge racism in their community.

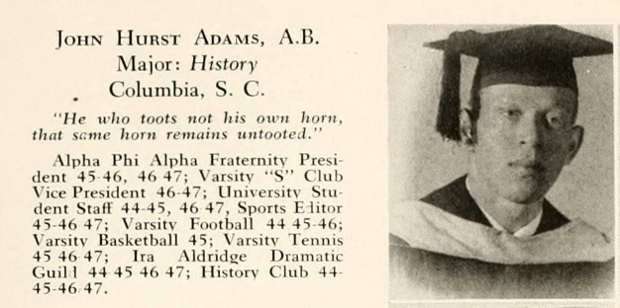

Adams was also involved with sports. Black colleges in the area would sponsor events and programs for youth in which guest speakers came in to teach sports fundamentals. Adams attended many of those events, and they helped him develop his athletic skills and confidence. By his own admission, he was never a great athlete. But in high school he lettered in four sports (basketball, football, baseball, and tennis), and when he attended college at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, North Carolina, he spent time on the basketball, football, and tennis teams. He also served as sports editor of the student newspaper.

Clearly, sports were a central part of his early life. When asked to recall the most important and formative influences during his college years, two of the three people he mentioned were coaches: football coach Eddie Jackson and tennis coach L.C. Coleman. Adams serves as evidence for the argument made by historian Derrick White, who has suggested that sports (especially football) at Black institutions were “one of the most critical sources of Black pride and producers of Black manhood in the twentieth century.”

After graduating from Johnson C. Smith in 1948, Adams’ sports career ended. He shifted his focus to the church, pursuing his calling as an AME minister. He also enrolled at Boston University’s School of Theology, overlapping for a few years with Martin Luther King, Jr. Although he was never in King’s inner circle, the two were friends. Adams remained connected to King over the years, and he generally patterned his own activism and philosophy on King’s approach.

Waco, Texas

Adams’ first major responsibility came in 1956 at the age of twenty-nine—the same year he married Dolly—when he was named president of Paul Quinn College, an AME-affiliated HBCU in Waco, Texas (the school has since moved to Dallas). He led Paul Quinn from 1956 until 1962 before moving to Seattle to serve as pastor of an AME church.

Adams’ tenure at Paul Quinn came just as the civil rights movement was gaining national momentum and inspiring a white backlash. Brown v. Board of Education, decided in 1954, declared an end to the “separate but equal” doctrine that had given legal sanction to segregation since the 1890s. In 1955, the Montgomery bus boycotts began, bringing national attention to both segregation and direct action strategies to overthrow it.

This was the context Adams was entering when he and Dolly came to the segregated town of Waco. Soon after they arrived, the Ku Klux Klan welcomed them by burning a cross on their front yard.

Adams’ responsibilities to lead the college meant that he had to be strategic and careful in his activism. His primary task was to secure funding to keep Paul Quinn afloat and perhaps even enable its expansion. That required support from white donors and community leaders in Waco as well as support from Black constituents.

But Adams could not stay silent. He introduced young Black people to the world of civil rights activism, driving van loads of Paul Quinn students to meet and listen to Martin Luther King, Jr speak. He also raised his own voice. In a 1958 radio address, for example, he encouraged Waco’s white residents to work creatively to build an interracial community that reflected Christian values. “Let us then proceed with deliberate speed and of deliberate minds to fulfill the American ideal of democracy and the Christian ethic of brotherhood,” he urged. In 1962, he and Dolly marched on the picket lines to protest the hiring practices of a service station located near Paul Quinn College. The business served an almost entirely Black clientele but refused to hire Black employees.

Adams also worked behind the scenes. In 1961 a handful of Paul Quinn students began to adopt the sit-in tactics used to integrate businesses elsewhere in the South. Wary of becoming a flashpoint for controversy, Waco’s white leaders asked Adams to put a stop to the demonstrations. When Adams informed them he couldn’t do this, city leaders organized a round of secretive talks that eventually led to the quiet desegregation of Waco’s downtown businesses.

In later interviews Adams was generally positive about his experience in Waco, as was Dolly, who said it was a “very segregated country town” that was nevertheless “an easy place to live” compared to other communities. In the 1970s, when Adams was appointed Bishop in Texas, he and Dolly returned to the city. Malcolm Brogdon’s mother, Jann, went through high school there, while Dolly enrolled at Baylor as a graduate student and earned her doctorate in education.

Dolly eventually became a Baylor alum, but neither she nor her children would have been able to enroll at Baylor during Adams’ tenure at Paul Quinn. In 1962, the year Adams left Waco for Seattle, Baylor University remained segregated. It would not accept its first Black student until the following year.

Hell-Raiser for Civil Rights

The restraints that Adams might have felt because of his responsibilities to Paul Quinn College disappeared when he moved to Seattle. There, he was the pastor of an AME Church. He only had to answer to his Black congregants and fellow AME leaders, freeing him to speak out on any issues towards which he felt God’s call. Adams quickly earned a reputation as a leader and agitator, helping to organize demonstrations and protests to address job and housing discrimination, economic and education inequality, police brutality, and more.

“I was the demonstrator and noise-maker and hell-raiser on behalf of civil rights, while other people did the negotiations in the corporate offices and in the political offices,” he later recalled.

The first major civil rights campaign for Adams was in opposition to housing segregation. Like most northern cities, Seattle’s white residents used a variety of tactics to bar Black people from moving into their neighborhoods, including restrictive covenants, redlining, and informal agreements by real estate agents. In the late 1950s Seattle’s Black community began organizing to overturn these practices. One piece of their strategy was to get an open housing ordinance passed that would ban housing discrimination.

Adams joined in with this work. In 1963, as Seattle’s leaders debated the proposed ordinance, Adams spoke at a hearing on behalf of the city’s Black community. He didn’t need much time to make his point. “The problems of prejudice, segregation and discrimination in America are the moral problems of the white community,” he declared. “We know this and you know this. Your right and resolute action is the only answer and your capacity to take that action is the only debate.”

After delivering his speech, Adams and his fellow Black activists walked out of the room.

Although the city council passed the ordinance, when it was put up for a city-wide referendum in 1964 it was soundly defeated. The New York Times covered the aftermath and talked with Adams about his frustration. It was a harbinger of the battles to come as the civil rights movement shifted in focus from desegregation in the South to the racist practices embedded in northern cities. In some ways, it was a struggle more difficult than in the South. There, the battle lines were more clearly drawn. In the North, Adams noted, “everyone seems to be your friend, yet little is done.”

Adams also confronted police brutality. In 1965 after a Black man was killed by Seattle police, Adams organized “freedom patrols” to monitor the city’s police force. Groups of citizens signed up to track and follow the officers, hoping to ensure fair treatment by either preventing or documenting abuse.

John Hurst Adams organizing a Freedom Patrol. Source: Museum of History and Industry, Seattle, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 2000.107.131.21.01.

It was not a new idea. Adams would later explain that he adopted the concept from his father, who had used it in South Carolina in the 1930s. In the 1960s the tactic would become most closely associated with the Black Panthers, who organized in 1966 with a focus on “policing the police.” But Adams was doing it a year earlier in Seattle—albeit without guns brandished as the Black Panthers preferred.

The Militant Black Church

For Adams, his work to achieve civil rights and equal opportunity was inextricably tied to his faith. He saw justice work as an essential part of what it meant to be an AME Church leader. “The tradition of our church is one of militance, both in the faith and militance in the pursuit of justice,” he later explained.

Because of this, he was especially frustrated when white Christians used religious justifications to work against the cause of civil rights. In 1965 when a group of white Protestant leaders in Seattle spoke out against a school integration plan, Adams called them “ministers of a diluted gospel” who opposed any “action which disturbs their comfortable pews.”

In 1967, he told an interviewer that the civil rights movement was a crucial test for American Christianity—one that most white churches were failing. While he acknowledged that some national church bodies had offered declarations of support for racial equality, he also noted that “it’s too often the Bible-shouting Christians who are opposed to Negroes gaining their rights.”

Because Adams recognized that white Christians leaders, whether they liked it or not, answered to a sizable number of constituents who opposed the priorities and goals of the civil rights movement, he could not trust them to lead civil rights campaigns. This made him sympathetic to the Black Power movement. “Black power refers to purpose, not the color of the participants,” he explained in 1967. “If whites in the civil rights movement can bend their skills and their energy and devotion in the acquisition of black power by powerless blacks, wonderful. If they want to make the decisions, to set the pace, that’s something else. They can forget it.”

Adams did not align with the nebulous Black Power movement on all matters. Historian Quintard Taylor has pointed out that by the time Adams left Seattle in 1968, his insistence on integration as a movement goal was being challenged by new and younger Black leaders in the city.

Yet even if Adams saw integration as an important aim, he focused much of his efforts on cultivating and developing Black pride and power. His time leading a church in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, from 1968 until 1972, is a case in point. There he developed an educational program for Black children in the neighborhood that focused on teaching Black history. The goal, he said, was to cultivate “Black pride without white hate.” Later in the 1970s, after being appointed Bishop in the AME Church, Adams helped to organize the Congress of National Black Churches—an effort geared towards consolidating and amplifying Black Christian voices and concerns.

Much of his work from the 1970s until his death in 2018 involved leading and supporting the AME Church and other Black institutions and leaders.

Adams’ Legacy Today

Of course, Adams continued to campaign for social justice even as he worked to strengthen the Black church. One of the last major racial issues for which Adams received national publicity came in the 1990s when he campaigned for the removal of the Confederate flag from South Carolina’s capitol. He was only partially successful. In 2000, South Carolina lawmakers reached a compromise in which they removed the flag from the capitol dome while placing a similar Confederate flag at a memorial on statehouse grounds. Only in 2015, after white supremacist Dylann Roof entered Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and murdered nine Black people, did South Carolina finally remove the flag entirely.

It was in the midst of the 1990s campaign to remove the Confederate flag—one more justice issue in a lifetime full of them—that Adams came back full circle to his younger days as an athlete. Speaking in 1994, he discussed different strategies that could be deployed to force South Carolina’s hand. One of them involved sports. “What would happen if all the black athletes at USC (University of South Carolina) and Clemson decided they couldn’t play for a state that flies a symbol of slavery over its capitol?” he asked.

His hypothetical question, raised sixteen years ago, resonates today. The specific issue of the Confederate flag flying over South Carolina’s capitol has been resolved. But numerous injustices remain for Black people—from the continued presence of Confederate monuments and symbols on public property, to discrimination and disparity in policing, housing, jobs, education, and more.

It’s precisely because of those injustices that Black athletes, including Malcolm Brogdon, are increasingly recognizing their power and platform and making their voices heard. When they do, they are carrying on the legacy of John Hurst Adams and so many others who have come before—a militant activist for faith and for justice.

Sources

“Bishop John H. Adams,” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/adams.htm [includes an interview posted to YouTube].

Dolly Adams, Interviewed by Larry Crowe on December 13, 2012, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive, https://www.thehistorymakers.org/.

“Groups on Both Sides of Flag Issue Rally,” Charlotte Observer, July 24, 1994.

John Hurst Adams, Interviewed by Ed Anderson on November 29, 2005, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive, https://www.thehistorymakers.org/.

Les Rodney, “Negro Minister Warns Race Problem Barely Dented,” Long Beach Independent, January 27, 1967.

“Minister Presses for Fair Housing,” New York Times, April 13, 1964.

“Paul Quinn President Discusses Race Relations,” Waco Tribune-Herald, February 9, 1958.

Quintard Taylor, “The Civil Rights Movement in the American West: Black Protest in Seattle, 1960-1970,” The Journal of Negro History (Winter 1995): 1-14.

“School Integration Feud At Brisk Boil In Seattle,” Salem Statesman, March 21, 1966.

The Golden Bull [Johnson C. Smith University Yearbook] (1947), available online at Digital NC, https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/28323?ln=en#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&r=0&xywh=-1744%2C-176%2C5783%2C3514.

“The Seattle Open Housing Campaign, 1959-1968,” Seattle Municipal Archives, https://www.seattle.gov/cityarchives/exhibits-and-education/online-exhibits/seattle-open-housing-campaign.