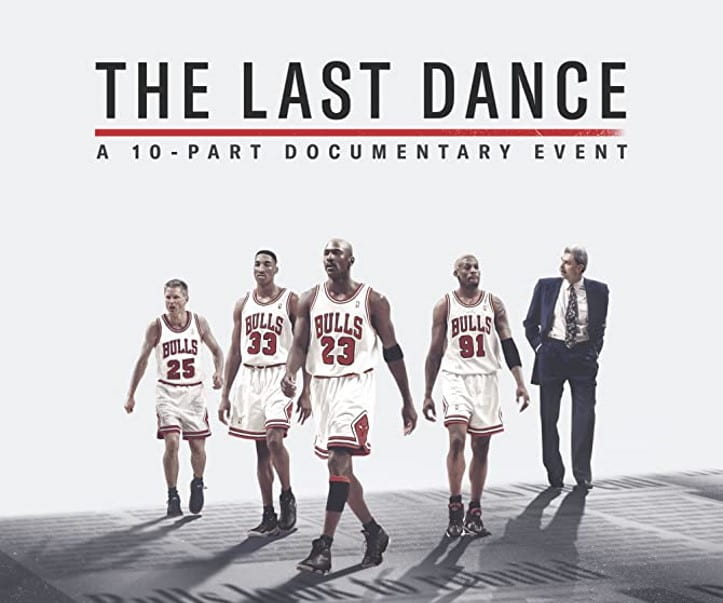

The ten-part documentary on Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls has finally come to an end. If you’re like me, you’ve been eagerly anticipating The Last Dance each Sunday night, appreciating the chance to take in a sports event—to reminisce, talk, and debate about hoops.

If you’re a Christian involved in sports, perhaps you’ve also been thinking about MJ’s story in light of your faith. Sports ministry organization Athletes in Action has been publishing recaps each week with this theme in mind, as has Timothy Thomas over at Christ and Pop Culture . I’d like to add a few points for Christians to consider as well. So here they are, three ideas I’ve been reflecting on as I’ve watched The Last Dance.

#1: Beware the “sidedoor” prosperity gospel

Would Michael Jordan have been a better basketball player if he had been a committed Christian?

For those outside the Christian sports ministry orbit, this might seem like a silly question. You might think “Of course not, how could he have been better?” But within sports ministry it is more complicated, because it gets at the heart of a persistent idea found within our culture: that there are sports performance benefits to Christian identity.

This idea is not quite the same as the “normal” prosperity gospel—the belief that God grants us health and wealth and success if we only have faith enough to ask. While some Christians in sports do embrace the prosperity gospel, most in sports ministry reject it. Most don’t make direct links between being a Christian and winning a game.

But there is similar and more subtle idea—let’s call it the “sidedoor” prosperity gospel—that is common in sports ministry. I know, because I embraced it as a high school and college athlete and because there are still parts of it that I hold onto.

It goes something like this:

- Christians should not find their identity in athletic performance—in winning games or awards. Instead, they should find their identity in Christ. Win or lose, they can trust that God loves them the same.

- When Christian athletes and coaches put their identity in Christ, they will find that they are freed from the burdens and anxieties of performance-based identity. They will be able to face the high and lows of sports with confidence that their God-given value does not change based on their performance.

- Freed from those burdens, Christian athletes and coaches will actually perform at their best.

This “sidedoor” prosperity gospel does not guarantee wins. It does something more subtle. It says that you can maximize your athletic potential—and thus have a better shot at winning—by finding your identity in Christ.

Tom Landry, legendary Dallas Cowboys coach, articulated this logic in the 1970s:

It’s not that we have God on our side. But I know I’m a better coach because I’m a Christian. The reason I say this is because the thing that keeps all of us from using our whole talents are our own fears, anxieties, and doubts. We fail to fulfill our complete potential. Once you accept Christ, and put all the fears in His hands, they go away and therefore, an athlete will perform with more confidence than ever before.

Michael Jordan poses a problem for this idea. Whatever his religious beliefs might be, it’s clear from The Last Dance that Christian faith was not part of his identity as an athlete. Would MJ—the best basketball player of all time—have been a better basketball player if he found his identity in Christ instead of in his desire to be better than everyone else?

I don’t think so. And there are plenty of other highly successful athletes and coaches with whom we could make the same point: Bill Belichick and Tom Brady come to mind.

Now, it’s quite possible that some athletes and coaches have found that commitment to Christ leads to improved performance. I won’t dispute that experience or tell Tom Landry he’s wrong about the personal benefits of his faith. But I don’t think it always happens. And I don’t think we should imply or suggest that improved athletic performance will always come from embracing a Christian identity. God works in people’s lives in complex ways and in a process that takes time. He promises to never leave or forsake us, but the “results”—the “fruits of the spirit” that He seeks to produce in us—do not always match up with the values and traits that lead to athletic success. And they don’t happen on a timetable that we can control.

So let’s learn from Michael Jordan, the greatest basketball player of all time—who did it all without turning to Christ. Let’s not preach a “sidedoor” prosperity gospel with athletic performance as the payoff. Christ offers us abundant life, but in ways that we might not envision or imagine.

#2: Michael Jordan’s success was driven in part by toxic, unhealthy obsessions that Christians should not try to emulate

Through The Last Dance we see example after example of Michael Jordan nursing petty grudges and remembering slights, real and imaginary. LaBradford Smith sarcastically told him “nice game.” Isiah Thomas refused to shake hands after losing in 1990. Karl Malone won an MVP. Clyde Drexler claimed he was on Jordan’s level. George Karl ignored MJ at a restaurant. Byron Russell told a then-retired Jordan he could lock him down. The list goes on and on.

And those were MJ’s opponents. His teammates faced his wrath, too. We learn that he punched Steve Kerr, we watch him berating Scott Burrell, and we hear from B.J. Armstrong, Bill Wennington, and numerous others how difficult it was to play with him. Indeed, the examples the documentary shows are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to MJ’s treatment of teammates. He cultivated an environment of fear and intimidation, defending his leadership style with an appeal to results: the Bulls won. The ends justified the means.

Forget the fact that MJ’s “that’s why we won” justification is debatable. It’s quite possible his team would have won just as much without his constant bullying. More important is that Christians are called to follow a different leader, one who commands us to love our enemies and to sacrifice ourselves for others. Winning by the world’s standards does not automatically make our conduct right or righteous. And winning does not justify intimidation and bullying. Christians are called to something greater.

When it comes to leadership, motivations, and treatment of teammates, we should not want to be like Mike.

#3: Michael Jordan’s flaws do not define him

Confronted with MJ’s failures and pathologies, it’s easy to throw him out entirely as a person worthy of our admiration. That’s the conclusion Joel Anderson reaches in a much-read essay for Slate. Anderson determines that Jordan was nothing more than a winning-obsessed tyrant, with nothing to teach us.

But I think Christians should not be so quick to dismiss and dehumanize Jordan. We can live with tension, recognizing him as a deeply flawed person who nevertheless possessed qualities we can admire and relate to. Read Roland Lazenby’s Michael Jordan: The Life and you’ll get a fuller and more nuanced understanding of Jordan as a person. And while it is true that The Last Dance does not go deep into MJ’s life beyond basketball, we do get some glimpses of his humanity.

We can empathize with the pain he felt over his father’s death, sobbing on the locker room floor as his emotions spilled out.

We can admire the way he loved and cared for his security guard and friend, Gus.

We can appreciate the grit and determination he displayed, both in practice and in games.

We can learn from the way he evolved and adapted his game to fit new circumstances and styles of play.

We can even be inspired by his failures. For someone who supposedly valued winning above all else, Jordan had a funny way of showing it. He retired at the top of his game in 1993 to play a sport he had not played since high school. Jordan started his baseball career knowing full well that he would not be winning anytime soon—and yet he did it anyway.

Then there is Jordan’s second return (which The Last Dance does not mention), coming out of retirement for one last go with the Washington Wizards. There were some who told Jordan not to do it. They told him to think of his legacy, to maintain the image of perfection that we see at the end of The Last Dance: game six, arm stretched toward the hoop, ball swishing through the net. A game-winning shot in a championship-winning game to end a legendary career.

But Jordan wasn’t playing for someone else’s idea of a perfect legacy. He knew that the Wizards were not a title-winning team. But he wanted the challenge. He wanted to compete. His willingness to take on the impossible goes against the idea that winning was all that mattered to him.

And it’s a quality we can admire, even if we should be careful not to look to MJ as our model of success and leadership.

What do you think? Agree or disagree, feel free to reach out on twitter to keep the conversation going.