By Alexander Abichou, PhD

‘[Browning] borrowed his jewels from the East and from the West; from art, from nature[…] from legend and history; from fancy and imagination [as well as] poets, painters, dervishes, saints [ and] took them all as the colours of his scenery, the figures in his drama, the sphere in which his imagination worked’ (Browning Society Papers, Sixth session, 1886-7. Forty-Fourth Meeting, Friday, October 29, 1886. pp.165-6)

Having traversed acres of prairie connecting the highways of Dallas-Fort Worth to Waco, I arrived at Baylor University to visit the unique Rare Books and Manuscript Collection at the Armstrong Browning Library which serves as a testimony to the life and writings of the Browning family and exemplifies a level of academic dedication (from inception to present) which would prove to be as endearing as it was informative. Although the quietude of the ABL stood in stark contrast to the grandiose lone star state that encompassed it, there was a warmth which resonated across the pomegranate engravings of the library doors, the minimalist walls of the Mark Rothko chapel, and the endless fields surrounding Gatesville’s Last Drive-In Picture Show. I had undertaken the fellowship as a means of broadening the scope of my current monograph, Mythographic thought and Islamic theosophy: From early Romanticism to Late Victorianism, focusing on Percy Shelley and Robert Browning as the respective exemplars of their age for determining a mythopoetic form of Orientalism where Eastern theological concepts were creatively integrated into a poetic oeuvre encompassing multiple traditions re-presented for contemporary audiences. I aimed to uncover details regarding the circles engaged in mythographic and Orientalist scholarship among Browning’s immediate acquaintances to determine how discussions pertaining to the evolution and role of myth vis-à-vis Christianity informed his depictions of Islamic personages and concepts. For the subsequent month, therefore, I was eager to immerse myself both in the archives as well as Texan culture which had previously been an unknown quantity due to never visiting this part of the United States. Neither aspect would disappoint.

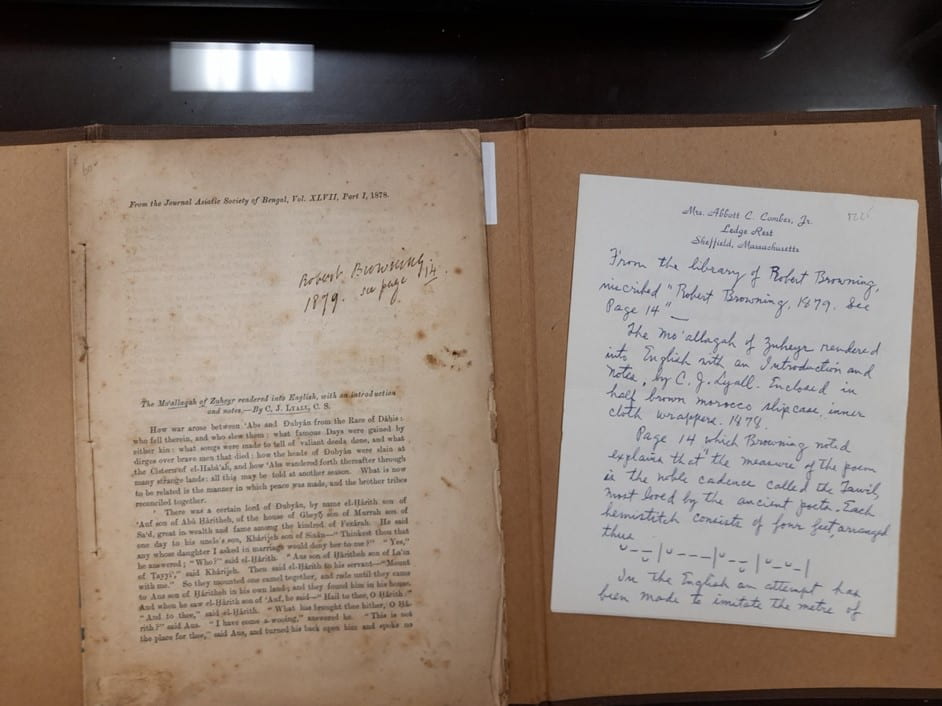

When discerning the nature of Browning’s exposure to Islamic intellectual history, it was pivotal to examine his interactions with the Arabist, Charles James Lyall, prompting me towards a series of correspondences between both parties as well as the drafts of critical editions for Arabic and Persian literature that Lyall translated and sent to his treasured companion. On December 13th 1884, Lyall offered linguistic corrections for Ferishtah’s Fancies which extended beyond simply noting alterations to be made for names such as, ‘Tahmasp,’ or, ‘Rakhsh,’ but also providing etymological insight into the lineage of these Persian and Arabic words from Hakim, signifying ‘Ruler, giver of commands [derived ] from hikmat, wisdom’, as well as Firdusi, connoting ‘paradise.’ The letter highlights Browning’s relation with Lyall as characterised by a growing exposure to classical Oriental literature with the British Arabist casually gesturing, ‘you may remember certain translations of old Arabian poetry of which I ventured to send you copies from India a few years ago.’ The interlinguistic quality that Lyall afforded Browning’s Oriental poetics offsets a general tendency to completely translate the Other and instead, humbles the reader into a position where meaning can be deduced but not necessarily authenticated. This polysemic approach affords those foreign terms a space to where the historical significance must be consulted before presuming mastery without wholeheartedly removing artistic intent for those both uninformed and seeking to be exposed to fresh terminology. Acknowledging this polyvocal quality of Browning’s work, Lyall writes in his English rendition of the Mu’allakah of Zuhair (Ode to Zuhair) that the metre adopted in the seventh stanza of Abt Vogler resembles, ‘the noble cadence called the Tawil, most loved by the ancient poets’, with the page number for this passage being noted on Browning’s personal copy (see below).

Robert Browning’s copy of The Mo’allaqah of Zuheyr rendered into English: with an introduction and notes by C.J. Lyall. ABL Brownings’ Library X BL 892.71 Z94m 1878

Lyall’s Mo’allaqah proved a useful source of classical Arab history and literary style offering a tapestry of poetic conceits and formal idiosyncrasies relayed through annotated footnotes which Browning would condense into his own passages such as, the ‘Slit-eared, unblemished, fat, true offsprings of Muzennem’, echoing Lyall’s comment that, ‘[c]amels of good breed had a slit in the ear [making them] the offspring of a certain Muzannam’. Aside from repurposing Zuhayr ibn Abi Sulma’s pre-Islamic vocabulary, Lyall and Browning also discussed the merits of Omar Khayyam’s Sufism in a letter dated 21st January 1885 as the former argues that the Persian polymath was, ‘more of a Sûfi than he seems in a superficial view’, since his discomfort towards the Sufistic longing for absorption within a Divine Beloved did not necessarily derive from unbelief but rather a scientific proclivity which sought to maintain selfhood. Intriguingly this comment is prefaced with an acknowledgment of Browning’s already established familiarity of the topic, ‘Sûfism, as you doubtless know, looks upon all phenomena as manifestations of the One, who is God, and considers the end of all to be absorption in Him.’ Lyall also reminds Browning of a previous poetry collection containing unpublished works from Lebid ibn Rabi’ah, ‘[t]he piece of which I showed you a translation when I called on Thursday last is taken from this Dîwân [of Lebîd’s poetry]’, highlighting a continued interest from both parties to share their thoughts on Arabian literature and prompting Lyall’s high praise of Lebid as standing, ‘between the Old time and the New, between the Ignorance and el-Islâm’. Akin to Lebid occupying the horizon line of these distinct eras, Browning’s correspondences reveal a willingness to bridge disparate cultures within an informed Oriental poetics that incorporates linguistic, topographical and conceptual material from the rural expressions found in pre-Islamic odes to the sufistic divans of figures such as Khayyam and Firdowsi informing Browning’s dervishes, Moleykeh and Ferishtah.

Outside personal relationships, I also wanted to broaden the scope of my research to include the voices responding to Browning’s work either contemporaneously or in the immediate aftermath of his death as a means of bolstering the veracity of my approach to Browning’s Islamic mythopoetics by finding likeminded interpretations espoused in the writings of his Victorian colleagues and critics. I perused volumes of the Browning Society Papers to glean choice quotes that foreground unconventional attitudes to reading his Eastern poetry which might highlight how my own interest in Browning’s engagement with Islamic literature is reflected in readings conducted during his lifetime.

In due course, I uncovered a transcript of the forty-seventh meeting conducted Friday April 25 (1890) in which the notion of a semitic affinity throughout Browning’s writing is examined by Joseph Jacobs’s paper on ‘Browning’s Theology’ where he highlights the characteristic elements of obscurity, moralism and symbolism imbuing Browning’s literature with traits found in sacred texts – overcoming canonical distinctions between poet and theologian. Jacobs lauds Browning’s dramatic rendition of theological concepts for its inclusive approach to non-Christian imagery whereby such Talmudic or mythohistorical allusions indicate, ‘[a] certain sympathy with Jewish ways of thought and fancy’, and yet, acknowledges that these references largely stemmed from the poets’ Broad Churchism and were not necessarily, ‘very profound.’ During the committee meeting, Reverend Johnson develops Jacobs’s examination of Semitic thought in Browning’s literature by contesting that the connection between Jewish, Islamic and Broad Church monotheism are not as divergent as the essay implies, ‘[the] Arabians were the great Unitarians, and the Jews, as he was endeavouring to convince Mr. Jacobs, stood in a secondary position to the Moslems.’ Dismissing the binary distinctions Jacobs’s upholds for Jewish and Broad Church Unitarianism, Johnson sought to reinforce how, the ‘great founders of the Unitarian faith in the world’, following the collapse of the Roman Empire, ‘were the Arabians’, and as such, there was a need to recognise historic interconnectivity rather than dissimilarity when examining Browning’s Broad Church depiction of Oriental imagery. By recontextualising this discussion of Browning’s Unitarianism in light of, ‘Koran[ic references] to the sublimity of Allah’, Johnson widens the matrix of Eastern allusions available in his poetry beyond the Jewish mythohistoric figures noted by Jacobs (e.g. Abraham ibn Ezra and Jaehanan Hakkadosh) and insists, ‘the religious literature of the Arabians,’ was also relevant to a holistic discussion of Browning’s transhistorical poetics. Although Johnson acknowledges the importance of Jewish theology as a precursor to Christian thought, he also calls for a reappraisal of Muslim literature in spawning a genre of secular romances through the ‘unsurpassed’ Arabian Nights which delighted the Oriental imagination of key eighteenth and nineteenth century authors (e.g. Coleridge’s ‘Kubla Khan’, Tennyson’s ‘Recollections of the Arabian Nights’) and in turn, placed the ‘Mohammedans [at] the fountain-head of religious imagination [amongst the Eastern empires]’. By emphasising the dialogical rather than exclusionary nature of historical influence, Reverend Johnson acknowledges Islam was a central faith in shaping contemporary Western fancy with regards to the East and as a result, warrants inclusion within the dialogic web of Browning’s traditional influences, ‘[t]he Jews were intermediaries between the Moslems and the Catholic Church’. Echoing Johnson’s sentiment that Browning’s Unitarianism was amenable to a Qur’anic focus on God’s, ‘unweariedness, his sleeplessness, and his height above all created beings’, Frederick Furnivall (joint founder of the Browning Society) contrasts the standard Broad Church assignment of, ‘Christ in the place of God and […] the Holy Spirit on one side altogether’, against Browning’s monotheism which more distinctly echoed, ‘the one great God of the Jews and the Arabians.’ Although Dr. Furnival admits Browning’s work allows the godship of Christ, there remains an emphasis on, ‘God the Father [before] God the Son’, and an overarching belief in, ‘one God irrespective of persons,’ that engendered an empathy with Jewish and Islamic Unitarianism. In particular, Dr. Furnival suggests that Jacobs overlooks Browning’s Eastern poetics as a medium for critiquing certain traditional theological tenets often associated with Trinitarianism from, ‘Church sacraments [and] regeneration in baptism [to] apostolic succession’, where figures such as Abd-el-Kadr in Through the Metidja and the titular Muleykeh provide didactic lessons on the nature of miracles or the atonement of sins in an unorthodox guise.

It was fascinating to uncover those members of the Browning Society who gestured towards descriptions of Allah, The Arabian Nights and Islamic imperial expansion within wider discussions concerning the poet’s reimagination of non-Christian traditions whether it be Reverend Johnson’s recognition of Islam’s world-historical impact on secular romance literature or Dr. Furnival’s supposition that Browning’s sympathies aligned with a more staunch Semitic monotheism. Although neither thinker presumes deep acquaintance nor desire for authenticity, these early efforts expanded the notion of Browning’s Jewish affinity beyond Joseph Jacobs’s or Moncure Conway readings by incorporating Islamic verbiage within literary analysis as a means of foregrounding Abrahamic Unitarianism as the broader connective tissue driving Browning’s creative interest in, each ‘great branch[… of this] one great system.’

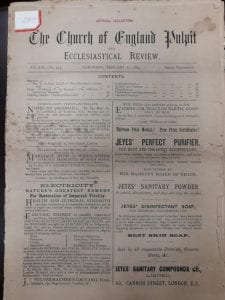

Review of Ferishtah’s Fancies in Church of England Pulpit and Ecclesiastical Review. Vol. 19. London, 17 January 1885, pp. 35-36. ABL Periodical Articles Meynell (Browning Guide #A0653)

In addition to the scholarly perception of Browning couched within committee manuscripts, I investigated newspaper reviews to deduce not only the reception of his Eastern-inspired output but also the content of articles surrounding these appraisals as his work can be noted appearing alongside other pieces espousing a pseudo-syncretic attitude towards the Orient. In particular, The Church of England Pulpit and Ecclesiastical Review provides an intriguing case study for discerning Browning’s position within this growing drive to solve contemporary problems with Eastern solutions. The nineteenth volume (January 17, 1885) contains a critique of Ferishtah’s Fancies as well as an adjoining discussion concerning ancient Jerusalem and its ties to modern Bedouin culture. The Review of Ferishtah’s Fancies exemplifies how susceptible the general audience was to Browning’s rendition of a Christian didactic narrative within an unfamiliar Dervish outfit for the critic offers a narrative breakdown of short stories comprising the work as well as a brief exegesis as to the core ethical lessons explored in each section. Although the piece is commended for blending poetic metre and philosophical concepts through the ‘supposed utterances of an Eastern sage,’ emphasis is placed on the moralistic insights that this Persian soothsayer can offer his Christian readership from the general theophanic outlook upon nature replete with divine signs for contemplation to extolling the potency of constant prayer. The reviewer exhibits a willingness to engage Browning’s Oriental anecdotes such as, ‘A Camel-Driver’ and ‘Shah Abbas’, where references to nomadic Bedouins or the Safavid King of Iran are not superficially questioned as irrelevant to struggles within Victorian society but rather embraced in a positive process of theological identity formation. Despite passages mimicking the Dervish rites of initiation or adopting the linguistic tone of Sufistic parables outlined in Lyall’s scholarly works, there is a an intense focus on the content and messaging of each ethical quandary that the arabesque design is appreciated as a vessel for relaying more universal truths.

Initially, I bypassed the paragraph prior to this review as simply a response to an article concerning the Eucharist where an anonymous reader offers an excerpt from William Thomson’s, The Land and the Book, (1860) but further investigation highlighted a curious thematic correlation as the East was similarly believed to possess a storehouse of forgotten traditions suitable for modern Christian interpretations. Urging his fellow believers to return towards the Holy Land for authenticity, the reader chastises the, ‘foolish asceticism of our civilisation,’ for placing a stigma on eating and drinking that, ‘did not exist in the Oriental mind’, arguing modern societies are unable to appreciate corporeal symbols whereas, ‘the Jews and other Eastern nations,’ (p.34) maintained a tradition of rejoicing in bodily senses and as such, were better equipped to understand the notion of Supper. It is intriguing that this reader would appeal to the ‘Oriental mind’ in order to conduct Biblical hermeneutics on the basis that the Middle East possessed a present geo-historical connection to the, ‘land where the World-made-flesh dwelt amongst men.’ In particular, a passage is cited where the Bedouin practice of welcoming guests through bread and dates (brotherhood; khuwy) is likened to the Eucharistic covenant. Although the book refers to Muslims as fanatic and ignorant, there remains a subtle acknowledgement of the transhistorical interconnectedness between the Abrahamic faiths via their current and past connection to Jerusalem as multiple denominations inhabit, worship or restore shared sites of cultural and religious significance, ‘many shrines of the Moslem, and other sects, owe their sanctity to events recorded in Biblical history.’(p.229) These cross-cultural intersections include: Joseph’s workshop being housed in the Muslim quarter and his tomb resembling ‘the common Moslem graves of the city’; contemporary Arab phraseology referring to casting the wife off as a slipper during divorce being associated with the narrative in Deuteronomy xxv. 7-10; and, the Bedouin law of hospitality practised through dabbihah (slaughtering a calf) thought to resemble an old custom practised by, ‘Abraham and Gideon, and Manoah.’ I believe it is not incidental that the Ecclesiastical Review situates this excerpt of William Thomson’s Middle Eastern travel narrative alongside their review of Ferishtah’s Fancies as this association highlights a willingness among Browning’s Christian readership to interpret his Jewish or Islamic allusions in a supplementary manner to inform their own theological identity. Likewise, Browning’s Eastern poetics can be contextualised within a greater movement towards refreshing contemporary Christian rhetoric by incorporating mythos previously dismissed on the basis of historical irrelevance.

By investigating archives unrelated to Browning’s personal correspondence, I realised how the humanistic tone of his religious poetics encouraged contemporary scholars and journalists to conduct a more hybrid literary analysis (incorporating disparate cultural codes) while also producing works that resonated with a Christian public seeking to reclaim traditional practices upheld in the East. I noted a mutually constitutive relationship form between Browning’s syncretistic approach to Eastern poetics shaping the way public figures approached Oriental tropes and the wider social shift towards integrating Arab or Persian lexis within cultural discourse which informed his own portrayal. The simultaneously innocuous and impactful nature of these references can be gleamed from an 1839 letter between Browning and Fanny Haworth where he wishes luck to two racing horses named, ‘Paracelsus’ and ‘Avicenna’, which are both references to Swiss and Persian physicians. Rooted within the mundanity of a horse race is the central character of Browning’s poem Epistle Containing the Strange Medical Experience of Karshish the Arab Physician for the titular protagonist is an amalgamation of these two formative figures who sought to similarly bridge the gap between religion and science and, as Hédi Jouad speculates, may even have derived his name from Koushayr (Avicenna’s professor). Regardless as to whether this scenario was coincidental or informative, it bolsters the narrative thread throughout these records that Middle Eastern and Islamic history had begun rooting itself into Victorian collective consciousness to the extent that neither Browning nor his associates would have found it strange to insert Qur’anic descriptions, Arab etymology or Persian poetics during their discussions.

Beyond the academic story unearthed from these tomes, my personal narrative at Baylor shall serve as a cherished memory thanks to the outstanding staff members who supported this endeavour and helped me piece together this image of Browning’s literary engagement with Middle Eastern culture. Christi Klempnauer and Laura French proved to be stalwart figures not only offering council when navigating the library system but also providing genuine, insightful conversations at the beginning and end of each day. Likewise, the experience would not have been possible without Jennifer Borderud’s acceptance of my application enabling this wonderful month spent as a researcher, guest and (now) ambassador for Waco. Although I acquired invaluable material towards my wider work on Browning, Shelley and Islam, it is these human moments that I will truly treasure, reminisce … archive.

bravoooooooooooo DR Skander Abichou

bonne continuation fière de toi mon grand