By Joshua Brorby, PhD, Postdoctoral Research Associate, English, Washington University in St. Louis; now Visiting Assistant Professor of English, University of Missouri

Joshua Brorby, PhD

When I began planning my research visit to the Armstrong Browning Library, the COVID pandemic was in its early days. I thought that by summer 2020 things might be opening back up, and if not in summer, then perhaps by Thanksgiving. As waves came and went, I deferred my plans several times. Finally in June 2021 I arrived in Waco, TX ready to delve into the archive, though with one minor problem: the dissertation I had begun when I initially applied for the fellowship was nearly finished. My research priorities had changed.

Between the drafting of the dissertation prospectus, the arduous writing of the first chapter, and the final stages of revision before the defense or viva, one’s arguments, investments, and critical apparatus are bound to change—sometimes drastically. As much as a dissertation is a verifiable contribution to a field of knowledge, it is also an exercise in self-knowledge, in coming to know one’s capacities as a critic and one’s fixations as a scholar. My dissertation-writing experience was no different. When I first considered visiting the ABL, my dissertation was focused on exploring and elucidating the myriad (often hidden) theories of translation that contributed to the omnivorous body of English literature in the nineteenth century. Think Edward FitzGerald, for example. Think Richard Burton. As I dug into this body of work—all the time keeping in the back of my mind Terry Hale’s claim that Victorian translations were often anonymous or “concealed” as adaptation—I discovered that a great deal of energy concerning translation as a process, with no guarantee of success, could be located in religious writing.

I began reading about F. Max Müller, the philologist and “scien[tist] of religion” who directed the Sacred Books of the East, a massive project to translate forty-nine Middle, South, and East Asian religious texts into English. And I scoured the writings and letters of George Eliot and Charlotte Brontë for clues to their thoughts on their own work as translators. Familiar mid-Victorian crises of hermeneutics and biblical interpretation, like the publication of Essays and Reviews and the controversy around Bishop Colenso’s The Pentateuch and the Book of Joshua Critically Examined, provided compelling contexts for my developing arguments. Thus, the ABL’s Theological Pamphlets Collection and its Tract Collection seemed the perfect archives in which to explore the religious milieux of the writers central to my dissertation, Faith in Translation: Rewriting Secularity in the British Empire.

By June 2021, as I made revisions to my fourth chapter and my introduction, my project had already started to change. I was looking ahead to the book manuscript, now in progress, which would begin to emerge from my dissertation. (I have changed the subtitle to Imagined Religious Pluralism in Victorian Literature.) In reading about the translation of non-Christian sacred texts into English, as well as the rediscovery of diverse Greek sources for the Christian Bible, I recognized a pattern in the work of both translators and novelists: they are often engaged in defining or imagining visions of pluralism that might come to actually exist in an unstable imperial context. They ask not only how Christian parties at odds might reconciliate—Protestants and Catholics, e.g., or Anglicans High, Low, and Broad—but whether the impetuses for religious belief and the yearning for something transcendent might be found across religious traditions and throughout religious history. How alike are Manu and Moses, as Eliot and others have asked? Does the literary, flexible reading of the Bible, suggested by Benjamin Jowett and Matthew Arnold, indeed disclose something universal about inspiration?

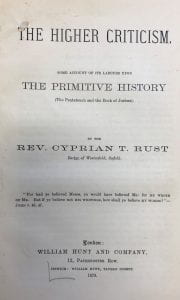

Cyprian T. Rust’s The Higher Criticism. London: William Hunt and Company, 1878. ABL 19th Cent OVZ BS1225 .R875x 1878

My search through the Pamphlets and Tract Collections became a search into the ways believers in the nineteenth century wrote about pluralism (not as the holding of multiple benefices in the Church of England, but as the conditions in which multiple religions coexist). The ABL’s organization of each of these collections by denomination was incredibly helpful. Much of the extant work in my dissertation concerned mainline Anglicans. With the ABL’s flexible search functions, I was able to dig specifically into materials from Roman Catholics, as well as anti-Catholic tract writers, and Unitarians—the latter of which were especially keen on discussing the problems of interfaith apprehension and overlap. James Martineau’s assertions for the authority of Reason over that of Scripture proved compelling. And I was pleased to find a book by his atheist sister Harriet Martineau—herself a translator of Comte—addressing itself “to the disciples of Mohammed.” Martineau’s 1833 essay anticipates some of the almost pantheistic claims Müller would make half a century later; in a dialogue between a Christian and Muslim, she declares, “There is no God but God,” uniting these two Abrahamic faiths under a banner of similitude. But as the essay progresses, Martineau takes a turn toward familiar Victorian supersessionism, based in the view that Protestantism lies at the endpoint of a quasi-natural development of religious evolution. Other religions merely pave the way for the message of Christ. This isn’t far from Müller’s own position. They are each of them pulled by this tension: between assertions of similitude and superiority.

J.S. Banks’s Christianity and the Science of Religion. London: Wesleyan Conference Office, 1880. ABL 19th Cent OVZ BR 127 .B3

The ABL’s religious texts collections also proved useful for exploring the “science of religion” as it was developed or criticized by writers not party to Müller and his extensive research network. The Rev. Cyprian T. Rust and the Rev. J.S. Banks—two figures with whom I was unfamiliar until coming to the ABL—both produced responses to the nascent science of religion in 1878 and 1880, respectively, that I uncovered in the archives. These Anglican hermeneuts each provide a window onto a mode of religious inquiry growing out of the earlier German higher criticism. As I found myself lingering over texts by names I had never read, I also found that the ABL was providing different pathways: both to new research and to opportunities to enrich old research. For instance, the plenitude of anti-Catholic tracts held by the ABL greatly added to my existing chapter on Charlotte Brontë’s Villette. A translated 1869 tract by M. Sauvestre gave my chapter a nice historicist twist, by which I might consider how anti-Catholic writing pitched celibate priests, nuns, etc. as having no family ties and, thus, disrupted the domestic organization of the state as based in the family. Considering Lucy Snowe’s total non-narration of her own family history in Villette, this correspondence to Catholic stereotype has continued to spur my thinking.

My time at the ABL was in part a personal sojourn from life in St. Louis during a pandemic. In June 2021 things had really lulled. And finally my partner and I were able to get out of St. Louis with our infant—his first big trip!—and explore a new city. Jennifer, Laura, and Christi at the ABL were incredibly helpful not only in my research but in planning family outings (a recurrent theme in some of these blog posts). Traveling to Waco brought us a sigh of relief. I think that in spending so much time scheming out my diss in its early days, I had closed off potentially fruitful avenues for further research. The wide-ranging collections at the ABL, along with its helpful finding aids and its fantastic staff, rekindled my interest in expanding on my project, something that may not have happened had I been able to visit when I first planned. What was needed, in a sense, was time away before revisiting my existing work. Such sojourns are a boon, especially when what waits on the other side is a rich and exciting archive brimming with possibility.