By Lesa Scholl, Ph.D., Head of Kathleen Lumley College, University of Adelaide, Australia

When I was preparing to come to the Armstrong Browning Library for my three-month fellowship, I had a range of plans that involved book proposals, chapter drafts, and well-thought-out structures for the research I was going to do. Previous experience should have warned me otherwise. I should have known that my project would become, in the words of Oscar Wilde’s Algernon Moncrieff, “quite exploded”—in the best possible way.

I first visited the ABL in April 2017, when I was primarily using the Nineteenth-Century Collection to examine Anglican pamphlets and tracts that engaged with the Eucharist and the way they talked about poverty, hunger, and social justice. On my last day in the library, I happened upon a particular pamphlet: Remarks on Fasting, and on the Discipline of the Body: In a Letter to a Clergyman. By A Physician (1848).

This pamphlet intrigued me, primarily because it was a medical doctor writing to a clergyman, not to speak against the practice of fasting, but to encourage appropriate ways in which to fast: ways that would promote bodily and spiritual health. He also gives a fascinatingly detailed description of what an appropriate diet ought to be—although he loses me when he tries to get me to refrain from coffee!

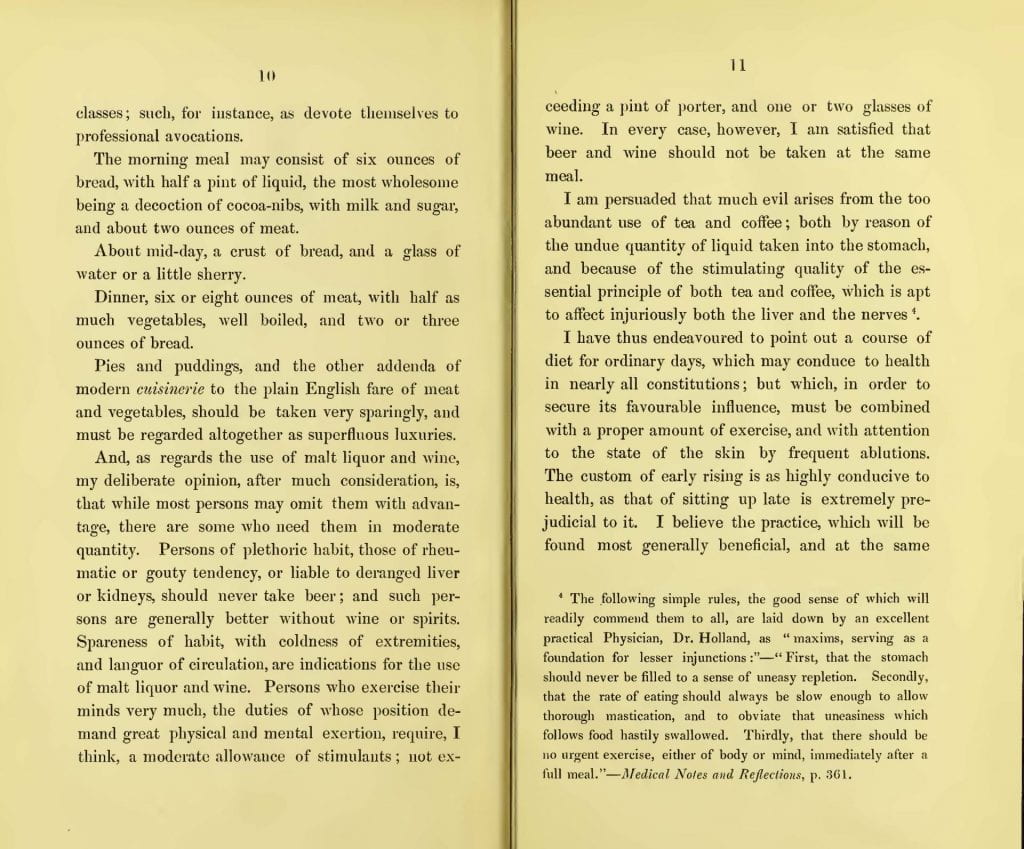

Pages 10 and 11 of Remarks details what the physician deems a regular diet so that one can ascertain whether they are eating too much or too little.

The discovery of this pamphlet led to my current book project, Fasting and Wasting: Religion, Nutrition, and Social Responsibility in Victorian Britain, which I’ve been working on during my semester at the ABL this year. Although I’d taken notes from the pamphlet, and had given papers relating to it since 2017, I was really excited to be able to hold it in my hands again. In this second full reading, I felt prompted to look at a particular text that it referenced. As I read Robert Wilson Evans’s The Ministry of the Body (1847), I realized that this was the text to which Remarks was responding: it was published in the previous year, also by Rivingtons, who had published Remarks, and my doctor-author was not only extremely flattering in his citations of Evans’s work, he proceeded to critique every criticism on fasting that the clergyman had presented! A doctor defending fasting to a clergyman—offering to teach the clergyman how to teach his flock to fast appropriately—isn’t exactly the expected trajectory.

I had found my clergyman, but my doctor continued to elude me. It took a number of Baylor librarians, the Wellcome Library, the Medical Heritage Library, the Royal College of Surgeons Library, the Lambeth Palace Library, and the National Library of Wales to find my answer: another Robert. Robert Bentley Todd, MD, one of the founders of King’s College Hospital in London, was identified.

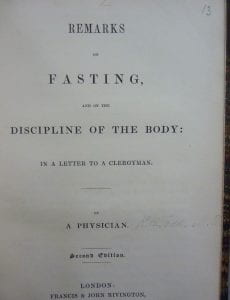

Lambeth Palace Library’s second edition of Remarks includes a nineteenth-century pencil annotation on the title page that attributes the pamphlet to R.B. Todd, M.D.

That Todd was the doctor is almost too good to be true. His career and his religious faith, and his determination to include religious training in the training of medical students, fulfilled the desire I had to make his pamphlet one of the centerpieces of my project. The question remains as to why such a prolific writer and influential figure chose to write the pamphlet anonymously. While I haven’t ascertained this answer fully, I suspect it was because it was well-known that Todd was good friends with John Henry Newman from his Oxford days, and it had only been three years since Newman’s extremely controversial conversion to the Roman Church. Given that Newman was also known for his more ascetic religious practices, including extreme fasting, and Todd’s own High Church persuasion, having the pamphlet signed may have influenced the readership to smell the dangers of popery. In fact, Todd was known to be deeply critical of extreme fasting, and, as his pamphlet details, held to fasting as food restriction more than complete abstinence—a stance that resonated with Todd’s and Newman’s fellow Oxfordian, Edward Bouverie Pusey’s attitude toward fasting in Tracts for the Times. Indeed, the reduction of portions rather than complete abstinence was seen as a way to prevent gluttony and intemperance at the end of the fast, and was believed to be more difficult than abstinence.

With my two Roberts—Evans and Todd—at the helm, my research over the semester stretched out into the conversations that were occurring between medical doctors and theologians within nineteenth-century Britain, and the way in which these conversations impacted understandings of social responsibility and public health, as well as spiritual and moral wellness. The ABL introduced me to many sources I hadn’t encountered before, such as the multivolume Bridgewater Treatises (a collection of books written by theologians and medical scientists on the natural sciences as evidence of the glory and power of God manifest in the earth) and the Rivington Theological Library, both of which revealed the deep connections of thought and ethos between medicine and religion in the Victorian period.

The conversation became, as I should probably have expected, much larger and more exciting than I had anticipated. I had the opportunity to bring the materials together in a preliminary way at the ABL’s Benefactor’s Day, where I presented on Healthy Bodies, Healthy Souls: 19th-Century Medicine, Religion, and Literature.

- Armstrong Browning Library’s Benefactors Day Program and Reception

- Armstrong Browning Library’s Benefactors Day Program and Reception

- Armstrong Browning Library’s Benefactors Day Program and Reception

- Armstrong Browning Library’s Benefactors Day Program and Reception

The ABL’s collection of materials on Alice Meynell and Christina Rossetti aided me in this as well, particularly in accessing Rossetti’s theological texts. This process made me rethink again the structure of my project: I didn’t want it to seem like the women were writing the light literary material while the men wrote the serious medical and theological texts. Rossetti was, in fact, taken quite seriously as a theologian in the nineteenth century, although that was an unusual role for women of the time. (She also happened to be treated by Queen Victoria’s doctors, but that’s a story for another day!)

The majority of the research I’ve been doing at the ABL has engaged with the way in which nineteenth-century doctors and theologians were thinking about the relationship between the body and the soul, and the way that then relates to the social body: how does our impetus to care for our physical bodies affect the way we think about the bodies around us? Are we too spiritual, too busy seeking God alone through prayer and fasting, to notice His presence in the poor bodies in our streets? That question was the crux of the nineteenth-century debate on the role of fasting in the Church. Many thinkers, both scientific and religious, in ways worth pondering in our own age of excess, saw a place for fasting that was both spiritually edifying, but focused outward toward the community: fasting to sympathize and understand; fasting to curb luxury and self-indulgence in an age of excessive consumerism when so many were starving; and, perhaps most importantly, in the words of Pusey, “to give to the widow, or the poor, the amount of that which thou wouldest have expended upon thyself.”