The Face of the Deep: A Devotional Commentary on the Apocalypse. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1892 (ABLibrary 19th Cent. BS2825 .R65 1892)

Verses. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1893 (ABLibrary 19th Cent. PR5237 .A1 1893)

Rare Item Analysis: Creation in Context: Christina Rossetti’s “A Vain Shadow” in The Face of the Deep

by Ryan Sinni

Click here to visit an interactive timeline and map related to this post on Central Online Victorian Educator (COVE).

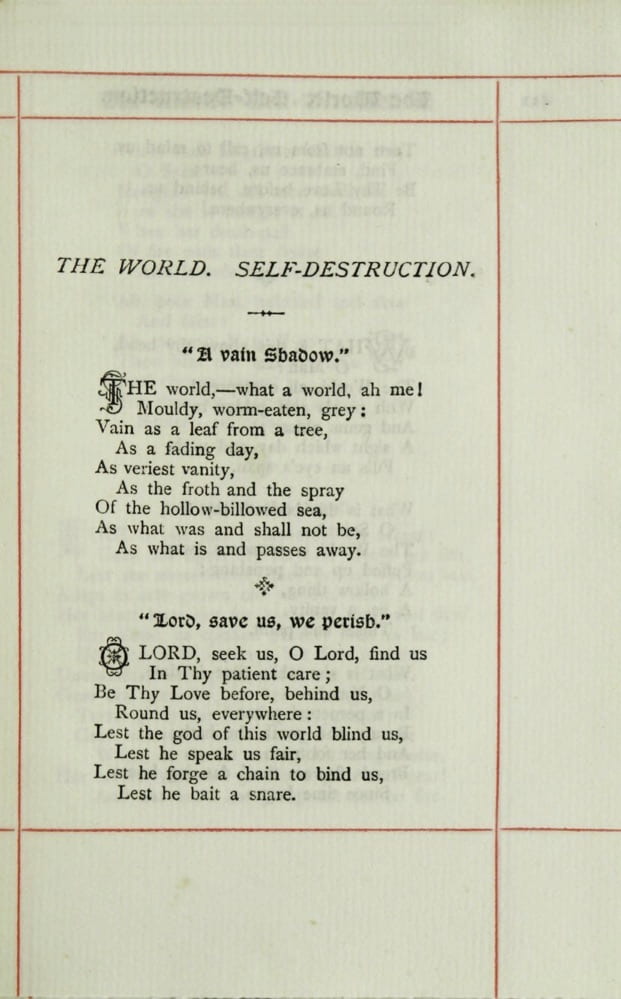

At first glance, Christina Rossetti’s “A Vain Shadow” might seem to exemplify an extreme sort of contemptus mundi. Many of her descriptions of the world highlight its fleeting character, as does the very brevity of the poem (only nine lines). Rossetti describes the world as not only fleeting, but also disgusting, calling it “Mouldy, worm-eaten, grey” (121). In Verses, a collection of Rossetti’s poems published in 1893 by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, “A Vain Shadow” opens a section entitled “The World. Self-Destruction.” These details might seem to suggest that Rossetti’s poem is meant to encourage hatred of the physical universe. But reading “A Vain Shadow” in its original context suggests that it is more complicated than it might at first appear. “A Vain Shadow” was originally published not in a collection of poetry, but in Rossetti’s The Face of the Deep: A Devotional Commentary on the Apocalypse, published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge in 1892. In this volume, it appears not as the first poem in a section on the vanity of the world, but in the context of creation’s praise of God. (The Face of the Deep can be found in the 19th Century Collection of the Armstrong Browning Library; Verses can be found in a subsection of this collection: the Women Poets Collection). Reading “A Vain Shadow” in its context in The Face of the Deep shows how Rossetti’s view of creation is not one-sided. Rather, Rossetti highlights different aspects of creation depending on her rhetorical context.

At first glance, Christina Rossetti’s “A Vain Shadow” might seem to exemplify an extreme sort of contemptus mundi. Many of her descriptions of the world highlight its fleeting character, as does the very brevity of the poem (only nine lines). Rossetti describes the world as not only fleeting, but also disgusting, calling it “Mouldy, worm-eaten, grey” (121). In Verses, a collection of Rossetti’s poems published in 1893 by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, “A Vain Shadow” opens a section entitled “The World. Self-Destruction.” These details might seem to suggest that Rossetti’s poem is meant to encourage hatred of the physical universe. But reading “A Vain Shadow” in its original context suggests that it is more complicated than it might at first appear. “A Vain Shadow” was originally published not in a collection of poetry, but in Rossetti’s The Face of the Deep: A Devotional Commentary on the Apocalypse, published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge in 1892. In this volume, it appears not as the first poem in a section on the vanity of the world, but in the context of creation’s praise of God. (The Face of the Deep can be found in the 19th Century Collection of the Armstrong Browning Library; Verses can be found in a subsection of this collection: the Women Poets Collection). Reading “A Vain Shadow” in its context in The Face of the Deep shows how Rossetti’s view of creation is not one-sided. Rather, Rossetti highlights different aspects of creation depending on her rhetorical context.

In The Face of the Deep, Rossetti includes “A Vain Shadow” at the conclusion of her commentary on Revelation 5:12, a verse that describes angels praising Christ for his death on the cross: “Worthy is the Lamb that was slain to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory, and blessing” (Rossetti 188). This may seem like an odd place to include a poem about the vanity of the world, but it makes good sense in light of the flow of Rossetti’s thought. In response to the angels’ praise of Christ for his death, Rossetti meditates on his sufferings. From considering the sufferings of Christ, Rossetti moves to describing the necessity of participating in Christ’s sufferings:

We must be congruous members of our Divine Head if we desire to share His beatitude; we must tread the same steps if we aspire to the same goal. Wherefore to serve becomes a privilege; to lack, an endowment; to think simply, a profitable exercise; to be sensible of weakness, a safeguard; to undergo shame, a medicine; to endure provocations, a stimulus to prayer. (189)

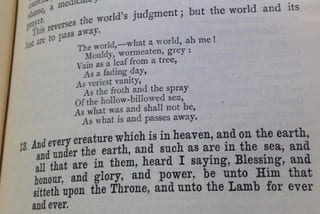

In this passage, Rossetti lists several paradoxes involved in following Christ. Things that seem to be loss are actually gain. Rossetti recognizes that her claims about what is valuable are the opposite of what people typically think. So she continues, “This reverses the world’s judgement; but the world and its lust are to pass away” (189). Rossetti seems to anticipate common opinion being an obstacle to her readers following Christ. To help remove this obstacle, Rossetti reminds her readers that those who mock at suffering for Christ will not remain forever. Rather, they and the things they desire will one day be no more.

It is here that Rossetti includes “A Vain Shadow.”  Knowing the preceding context of the poem sheds new light on how the poem can be read. Rossetti’s rhetorical end is to persuade her readers to imitate Christ. But she recognizes that the world’s opinion might be an obstacle. In order to reveal the folly of heeding the world’s opinion, Rossetti unveils the world as fleeting. It is the poem that does the unveiling. In other words, Rossetti has three nested persuasive ends. Her immediate end is to reveal the fleeting character of the world. Rossetti seeks in revealing the fleeting character of the world to demonstrate the weightlessness of the world’s opinion. Subverting the world’s judgement serves the ultimate rhetorical end of encouraging believers to follow Christ. Examining these nested persuasive ends shows that the poem’s descriptions of the world as fleeting and even disgusting are not the fruitless complaining of a bitter soul, but the didactic revelation of the world’s vanity.

Knowing the preceding context of the poem sheds new light on how the poem can be read. Rossetti’s rhetorical end is to persuade her readers to imitate Christ. But she recognizes that the world’s opinion might be an obstacle. In order to reveal the folly of heeding the world’s opinion, Rossetti unveils the world as fleeting. It is the poem that does the unveiling. In other words, Rossetti has three nested persuasive ends. Her immediate end is to reveal the fleeting character of the world. Rossetti seeks in revealing the fleeting character of the world to demonstrate the weightlessness of the world’s opinion. Subverting the world’s judgement serves the ultimate rhetorical end of encouraging believers to follow Christ. Examining these nested persuasive ends shows that the poem’s descriptions of the world as fleeting and even disgusting are not the fruitless complaining of a bitter soul, but the didactic revelation of the world’s vanity.

Vanity is not the only aspect of the world that Rossetti highlights in this context. The very words that follow “A Vain Shadow” are the words of Revelation 5:13, which describes all creation praising God: “And every creature which is in heaven, and on the earth, and under the earth, and such as are in the sea, and all that are in them, heard I saying, Blessing, and honour, and glory, and power, be unto Him that sitteth upon the Throne, and unto the Lamb for ever and ever” (Rossetti 189). Having just highlighted creation’s vanity, Rossetti turns to a passage that describes creation’s worship. Her commentary celebrates the praise the verse describes: “Absolute unanimity among all creatures. Though one have more, another less, all swell the hymn of unalloyed, unabated triumph. If stones also are crying out, it is not because any in heaven or on earth hold their peace: if those who still draw mortal breath speak, they supersede not voices from under the earth and from the sea” (189-90).

Rossetti points out that all creatures praise God, from the least to the greatest. She soon makes clear that she recognizes the apparent tension between creation as passing away and creation as praising God: “The present heaven and present earth must pass away, but meanwhile they praise God: the sea must be no more to-morrow, yet to-day it magnifies its Maker” (190). Rossetti’s use of the words “but” and “yet” suggests that creation’s praise might seem surprising in light of its vanity. But she ultimately maintains that creation, in its present form, is both fleeting and praise-giving; these two aspects of creation are not contradictory, but complementary.

Rossetti reveals the complexity of her understanding of creation in her use of the word “world.” In this context, the word “world” has at least two senses. Rossetti has first described “the world’s judgement”; in this phrase, “the world” refers to people who deny the paradoxes of following Jesus (189). In other words, it refers not to the physical universe, but to a group of people—namely, those who oppose Christ and his church. But in the very same sentence, Rossetti uses the word “world” in a more ambiguous sense. When Rossetti writes that “the world and its lust are to pass away,” it might seem that she is thinking simply of the worldly people she has just mentioned (189). But that Rossetti adds that not simply “the world” but also “its lust” are to pass away, she seems to have in mind not simply people who oppose Christ, but also the things they desire. Rossetti’s commentary on Revelation 5:13 supports this reading. Here, it is not people that “must pass away,” but “the present heaven and present earth,” a reference that clearly includes the physical creation in its present form (190).

It seems, then, that Rossetti is using the vanity of the present physical creation as an argument against listening to worldly people. That Rossetti uses the vanity of the former as an argument against listening to the latter suggests that she views the two as closely linked: the wicked are associated with a decaying creation in a way that the righteous are not. The biblical text to which Rossetti alludes, 1 John 2:15-17, lends support to this interpretation. In verse 17, the apostle John writes that “the world passeth away, and the lust thereof: but he that doeth the will of God abideth forever.” In this passage, John contrasts the vanity of the world with the stability of the righteous. The world’s vanity is only a problem for the wicked; the righteous remain despite the world’s decay. Like John, Rossetti sees the decay of the physical creation as a sign of the decay of the wicked. Rossetti does not present creation itself as evil (creation praises God!), but she does use its decay as an argument against heeding those devoted to the pleasures it promises.

Creation teaches the righteous not only by its decay, but also by its praise. Rossetti presents the praise of a fleeting creation as a model for Christian behavior: “For here we behold things transitory in company with things permanent uplifting praises: the former utilizing for praise the only time they have; the latter for identical praise anticipating the eternity which awaits them. This is to take our Master at His word when He said: ‘Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself.’” (190) In this passage, Rossetti presents creation as modeling obedience to Christ’s command not to worry about tomorrow. Just as creation praises God without concern for its future destruction, Christians should follow Christ without anxiety. Rossetti’s description of the vanity of the world and her description of its fleeting praise both find practical devotional application in the lives of her readers. These descriptions suggest that Rossetti has a multifaceted view of creation, and that she tends to highlight the facet appropriate to her rhetorical context.

Even in Verses, “A Vain Shadow” serves devotional ends. As noted above, “A Vain Shadow” appears in a section entitled, “The World. Self-Destruction.” A key theme in this section is the difference between the appearance of the world and its true character. To take just one example, an untitled poem in this section (which begins with the words “What is this above thy head, / O Man?”), contrasts in its third and fourth stanzas the world as it is now and the world as it will be:

What is she while time is time,

O Man?—

In a perpetual prime

Beauty and youth she hath;

And her footpath

Breeds flowers thro’ dancing hours

Since time began.

While time lengthens what is she,

O Saint?—

Nought: yea, all men shall see

How she is nought at all,

When her death-pall

Of fire ends their desire

And brands her taint. (122-23)

Rossetti presents these two contrasting stanzas in order to reveal the ultimate destiny of the world, despite its present appearance. In Rossetti’s commentary on Revelation 5:12, Rossetti’s readers face the temptation to regard too much the opinion of worldly people; in this poem, they face the temptation to build lasting happiness on a faulty foundation. But Rossetti addresses the latter temptations in much the same way as she addresses the former: by revealing the fleeting nature of the world, a reality that could remain hidden under a facade of permanence. Almost every poem in this section draws a similar contrast between appearance and reality. What this suggests is that even in its context in Verses, “A Vain Shadow” does not present itself as the self-expression of a jaded heart. Instead, it reveals the fleeting character of the world to those who might be tempted to set their hope upon it.

Examining “A Vain Shadow” in light of The Face of the Deep and Verses sheds light both on the poem itself and Rossetti’s understanding of creation. In her commentary on Revelation 5:12-13, Rossetti speaks about creation not primarily in order to express personal feeling, but in order to edify Christian believers. In her commentary on Revelation 5: 12, she describes creation as fleeting so that her readers will not fear worldly opinion. In her commentary on verse 13, she points to creation as an example of how to obey Christ’s command not to be anxious about tomorrow. In Verses, “A Vain Shadow” also appears in a didactic context: several poems in the same section reveal creation as fleeting in order to discourage readers from seeking lasting happiness in this present world. Together, these contexts demonstrate Rossetti’s complex view of creation and her appeal to different aspects of creation depending on her rhetorical situation. A further use of these rare items might include examining the context in The Face of the Deep of other poems in Verses. A particularly fruitful line of inquiry might be to examine the context of “Behold, it was very good,” a poem that presents a more obviously positive take on the physical universe. Another profitable avenue might be to compare the valences of the word “world” in The Face of the Deep with its various meanings in Scripture.