Letters:

12 August 1843 Thomas Westwood to Elizabeth Barrett Browning

2 September 1843 Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Thomas Westwood

26 September 1843 Thomas Westwood to Elizabeth Barrett Browning

21 October 1843 Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Thomas Westwood

The letters from Thomas Westwood are contained in the Browning Letters Collection of the Armstrong Browning, Library. Transcripts of the letters can be accessed digitally through the following link:

https://www.browningscorrespondence.com/

Scans of the letters, except for the final letter from EBB, can be accessed through the Browning Letters Collection of the Armstrong Browning Library:

https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/documents?returning=true

Texts of all of the letters, including the final letter from EBB, can be accessed through the online editions of the Browning’s Correspondence at this link:

https://www.browningscorrespondence.com/correspondence/search/

Rare-Item Analysis: Thomas Westwood’s and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Criticism of Tennyson’s Poems (1842).

By Olivia Taylor

The letters from Thomas Westwood are held in The Browning Letters collection at the Armstrong Browning Library.

The first reply from EBB, dated 2 September 1843 is held by Wellesley College in the Margaret Clapp Library, Special Collections.

The second reply from EBB, dated 21 October 1843, is held by the British Library, Westwood Manuscripts Collection.

The two letters are part of a longer correspondence about contemporary authors between the minor poet Thomas Westwood and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. A significant portion of the correspondence is devoted to Westwood’s criticism of Tennyson’s Poems (1842). EBB initially praises Tennyson warmly, but is somewhat convinced of Westwood’s claim that Tennyson’s poetry is beautiful, but lacks spiritual depth. To view a transcription of the four letters between Westwood and EBB in sequence, use this handout. The sections relevant to their discussion of Tennyson are highlighted.

Later views of Tennyson as a religious leader are further discussed in Andrew Hicks’ post on an illustrated version of Idylls of the King. https://blogs.baylor.edu/19crs/2020/01/15/layers-of-interpretation-moxons-illustrated-idylls-of-the-king-in-context/

J. Caleb Little also discusses posthumous views of Tennyson as a spiritual leader in her post on funeral hymns dedicated to Tennyson. https://blogs.baylor.edu/19crs/2020/01/15/hymning-tennyson-signs-of-a-national-hagiography/

This letter exchange is significant because it sheds light on the early reception of Tennyson’s poetry by his contemporaries, demonstrating skepticism about the merit of Arthurian subject matter. It contrasts sharply with the very positive views of Tennyson’s spiritual leadership in his later career. It also demonstrates that there was an expectation for some Victorian readers that the poet functioned in a similar role to that of a preacher or teacher.

While Westwood and EBB never met, they maintained a friendly correspondence between 1842-1845 (“Thomas Westwood” n.p.). Westwood’s letter-writing style is effusive, with many words underlined for emphasis. The volume of poetry they were discussing came at the end of a ten-year period of relative inactivity for Tennyson. Westwood sarcastically remarks on this in the September 26th letter: “I have heard that Tennyson is very idle—perhaps this will account for his so often taking up ready-made subjects instead of creating for himself.” Tennyson was, in fact, far from idle during this time—he continued writing and was dealing with several difficult personal situations (Cameron n.p.).

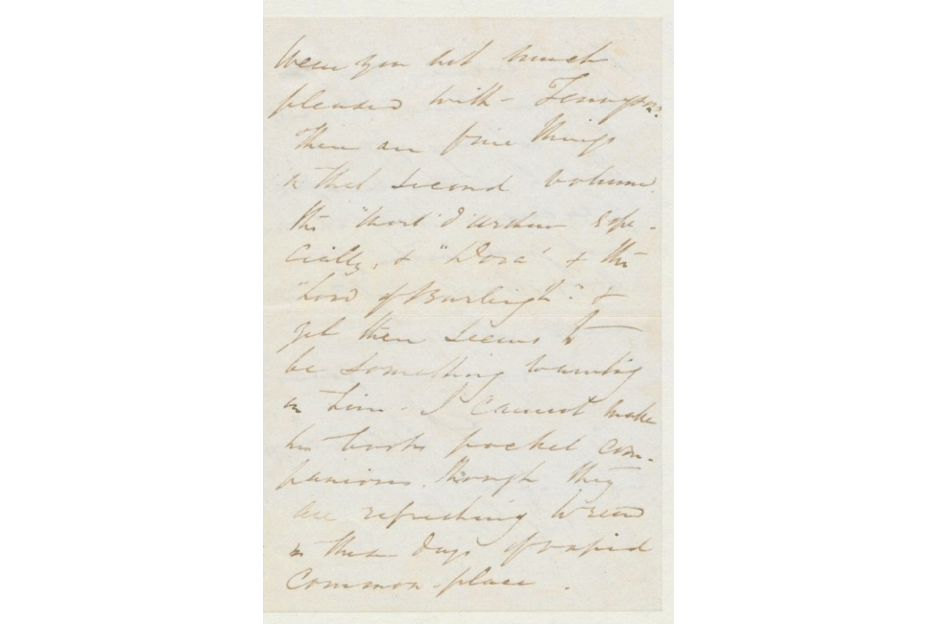

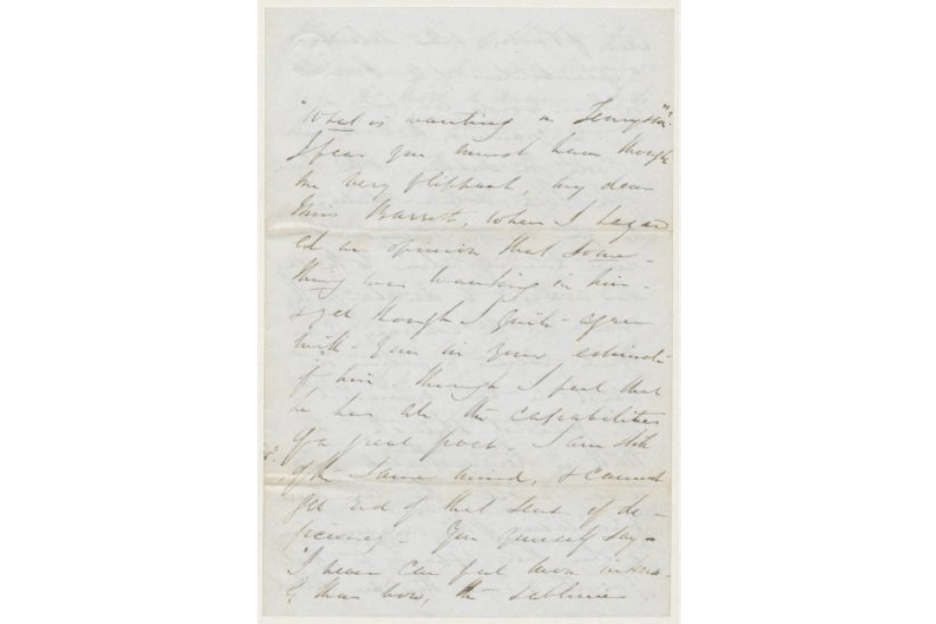

Westwood’s initial criticism is moderate: “There are fine things in that second volume, the ‘Mort d’Arthur[’] especially, & ‘Dora’ and the ‘Lord of Burleigh,’ & yet there seems to be something wanting in him” (12 Aug 1843). However, when EBB asks for clarification, he writes: “in his finest poems, –poems on which he was expended his greatest strength—no truth is demonstrated—no lesson taught—They are mere phantasies of the imagination, & when their appeal to that faculty is over, they are silent” (26 September 1843).

He then puts forth a bit of his own philosophy on the purpose of poetry: “Though it were absurd to apply invariably, the “cui bono” [i.e. “who benefits?”] principle to poetry, do you not think a great Poet, ought always to keep it in mind, & not, when he has wrapped the garment of his strength about him, merely dally with flowers, or “sport with the tangles of Nerina’s hair”? (26 September 1843).

A “great Poet,” according to Westwood, needs to make sure that his poetry provides some kind of moral or educational benefit—that it reveals some greater truth or moral lesson.

Westwood does cite Tennyson’s poem “The Two Voices” as an exception to this rule (26 September 1843). “The Two Voices” is a compelling dialogue between two voices that argue about whether or not the speaker of the poem should commit suicide, where the voice against suicide wins out (Tennyson 122-124). The complex moral and theological questions dealt with in this poem definitely fit within Westwood’s criteria for beneficial poetry, so it makes sense that he would cite this as an exception.

EBB’s reply to Westwood in the letter dated October 21st indicates that, at least from her perspective, the benefit a great poet should provide should be religious in nature:

You are probably right in respect to Tennyson—for whom with all my admiration for him, I would willingly secure more exaltation, & a broader clasping of Truth. Still, it is not possible to have so much Beauty without a certain portion of Truth—the position of the Utilitarians being true in the inverse. But I think as I did, of “uses” & [‘]‘responsibilities”, & do hold that the poet is a preacher & should look to his doctrine. Perhaps Mr Tennyson will grow more solemn like the sun, as his day goes on. In the meantime we have the noble “Two Voices”…He is not a Christian poet up to this time— but let us listen & hear his next songs. He is one of God’s Singers,—whether he knows it or does not know it. (21 October 1843)

Her criticism, then, is more balanced—she indicates that, according to her view, truly great poets should strive towards religious benefit in their poetry. She also acknowledges that it is not completely fair to judge Tennyson according to Westwood’s criteria. However, her statement that Tennyson is “not a Christian poet” is certainly a criticism.

After consulting one of her other letters to her cousin John Kenyon from the same year, it appears that her concern is not with what Tennyson himself believes, but with the way he writes about it. In this letter, she defends the use of the name of Christ in poetry: “I w[oul]d rather be a Pagan whose religion was actual, earnest, continual, .. for weekdays, workdays, & songdays, .. than I would be a Christian who, from whatever motive, shrank from hearing or uttering the name of Christ out of ‘Church’. I am no fanatic—but I like truth & earnestness in all things…What pagan poet ever thought of casting his gods out of his poetry?” (25 March 1843). Essentially, her concern with Tennyson is probably that his references to Christianity tend to be vague and noncommittal, rather than proclaiming Christianity in an explicit and enthusiastic way. From this standpoint, his poetry is not explicitly Christian poetry, therefore he is not a great poet-preacher. EBB makes clear in her letter to Kenyon that she does not view poetry and religion as things that can be separated.

These letters serve an important reminder that the standards by which we as modern readers evaluate texts may be drastically different from the original context in which they were read. The idea that clear Christian messages are integral to poetic excellence is pretty alien to the way we approach poetry. While EBB’s views obviously don’t speak for the whole period, they highlight the high expectations placed upon poets during the time period—they were expected not only to create excellent art, but also to provide spiritual instruction to their readers. Awareness of this dual expectation can reveal much about both the reception of Tennyson’s work, but also of the artistic choices made by EBB and Westwood in their own works.

For instance, Westwood would later publish several Arthurian poems including “The Sword of Kingship” in 1866 (“Thomas Westwood”) and The Quest for the Sancgreall in 1868 (Seccombe n.p.). “The Sword of Kingship” bears a striking resemblance to Tennyson’s Arthurian works, but his Christian messages are far more explicit—for instance, he directly connects Arthur’s birth to the birth of Christ in the poem (Westwood 15-17, 37). Westwood was probably working from several motives—he may have thought he could do better than Tennyson in terms of marrying subject matter with religious truths, or he may have been capitalizing on the cultural moment. Either way, the fact that Westwood made these comments upon Tennyson and later wrote his own Arthurian works indicates the strength of Tennyson’s influence. The explicit references to Christianity in these later poems may also indicate that Westwood sympathized with EBB’s belief that poets should not shy away from explicit discussions of Christianity.

Westwood and EBB’s conversation about Tennyson’s Arthurian works could be a helpful addition to class discussions of Tennyson’s influence, or as a way of showing how Victorian writers like Tennyson and EBB did not work in a vacuum—they were connected through a wide network of friends and acquaintances, read widely, and had complex opinions on others’ work. Those interested in using Westwood’s letters in a classroom setting might find this sample presentation helpful.

These letters indicate the complex reception of Tennyson’s religious poetry, and shed light on EBB’s priorities in composing her own poetry. It also demonstrates the expectation that nineteenth-century poetry needed to be spiritually edifying, rather than simply being viewed as “art for art’s sake,” so these letters could be useful in classroom discussions on the purpose of art.

Works Cited

Cameron, Julia Margaret. “Tennyson, Alfred, first Baron Tennyson (1809–1892).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sept. 2004. https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-1012231 Accessed 1 Apr. 2022.

Hicks, Andrew. “Layers of Interpretation: Moxon’s Illustrated ‘Idylls of the King’in Context.” 19CRS, 15 Jan. 2020,https://blogs.baylor.edu/19crs/2020/01/15/layers-of-interpretation-moxons-illustrated-idylls-of-the-king-in-context/, Accessed 1 Apr. 2022.

Seccombe, Thomas. “Westwood, Thomas. (1814-1888).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sept. 2004. https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-29141?rskey=vI5SAh&result=1. Accessed 1 Apr. 2022.

Tennyson, Alfred. “The Two Voices.” Tennyson: A Selected Edition. Edited by Christopher Ricks. Routledge, 2014, pp.101-124.

“Thomas Westwood.” The Brownings’ Correspondence, https://www.browningscorrespondence.com/biographical-sketches/?nameId=1953, Accessed 1 Apr. 2022. Westwood, Thomas. “The Sword Of Kingship.” In The Quest of Sancgreall, the Sword of Kingship, and Other Poems, 1868. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.baylor.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/sword-kingship/docview/2148102322/se-2?accountid=7014