Letters:

1. 13 December 1850 Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Mary Russell Mitford

2. 19 July 1871 Edward Dowden to Elizabeth Dickinson West

3. 25 September 1882 James Martineau to Roden Noel

Letter #1 is held in the Browning Letters Digital Collection of the Armstrong Browning Library and may be accessed at this link: https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/explore-the-collections/list/collections/6

Letters #2 and #3 are held in the Victorian Letters Collection of the Armstrong Browning Library and can be accessed at this link: https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/explore-the-collections/list/collections/7

Responses to In Memoriam: Early Comparisons of Tennyson through the Dialogue of Victorian Letters

By Abby Wills

Tennyson’s In Memoriam was published at the end of May 1850. Less than a month later, his acquaintances expressed curiosity about this new work. In a letter to Mary Russell Mitford on June 15th, Elizabeth Barrett Browning said, “We are very anxious to know about Tennyson’s new work ‘In memoriam’. Do tell us about it. You are aware that it was written years ago & relates to a son of Mr Hallam, who was Tennyson’s intimate friend & the betrothed of his sister. She has since married, I am sorry to say. I have heard through some one who had seen the m∙s. that it is full of beauty & pathos” (2860).[1] As this letter reveals, even before they had read In Memoriam, Tennyson’s acquaintances were expressing their opinions about it. As the months and years passed, correspondence among poets and critics revealed both praise for and skepticism of Tennyson’s poem. In the wake of his appointment to the poet laureate, these expressions demonstrate that Tennyson’s prominence provoked comparisons between In Memoriam and other works, revealed skepticism of Tennyson’s spiritual authority, and demonstrated that his poem remained a relevant cultural icon against which other texts were compared.

To illustrate the poem’s lasting role, I will examine three letters held in the Armstrong Browning Library’s Digital Collections (One from the Browning Letters and two from the Victorian Letters Collection) that address In Memoriam’s merits, limits, and spiritual significance. These three letters were written in December 1850 by EBB to Mary Russell Mitford, July 1871 by Edward Dowden to Elizabeth Dickinson West, and September 1882 by James Martineau to Roden Noel.

In the first letter, held in the Armstrong Browning Library’s Browning Letter Collection, EBB writes to her longtime friend, the writer Mary Russell Mitford. The two friends kept up a voluminous correspondence between each other, sharing opinions and news about other authors (and about EBB’s dog, Flush, whom Mitford gifted to EBB in 1841) (Stone). In this 1850 letter, written in small, compressed handwriting filling every bit of space in four pages, EBB talks about Elizabeth Gaskell and her new novel Mary Barton, Tennyson’s In Memoriam, various other contemporary poets, English society in Florence (where EBB and Robert Browning lived), and the Brownings’ son, Wiedeman.

Although EBB does not explicitly compare In Memoriam to other works, her praise comes immediately following a lengthy criticism of Mary Barton, in which EBB declares, “I wish half the book away, it is so tedious every now & then,—and besides I want more beauty, more air from the universal world—these class-books must always be defective as works of art.” In the following section, she begins, “As to ‘In Memoriam’” (2895, emphasis mine), signaling with “as to” that she is moving from one text to the next, implicitly comparing them. She continues:

the book has gone to my heart & soul .. I think it full of deep pathos & beauty. All I wish away, is the marriage hymn at the end . . . . Who that has suffered, has not felt wave after wave break dully against one rock, till brain & heart with all their radiances seemed lost in a single shadow? So the effect of the book is artistic & true . . . . he appeals, heart to heart, directly as from his own to the universal heart, & we all feel him nearer to us . . . . (2895, emphasis mine)

By using similar language as that in her critique of Mary Barton, EBB places In Memoriam as a standard of art and depth of feeling that Gaskell’s novel fails to reach. Instead of “wishing away” half of the book, EBB only “wishes away” the conclusion of Tennyson’s poem. Instead of being “defective” as a work of art, In Memoriam is “artistic & true.” While EBB requires “more air from the universal world” in Mary Barton, Tennyson’s poem succeeds in speaking “to the universal heart.” Thus EBB demonstrates that, just a few months after its publication, In Memoriam was held as a standard against which to compare other literary works. EBB’s praise is all the more striking because she was “Tennyson’s rival and a candidate for poet laureate in 1850” (Stone).[2] It is noteworthy that, even in a private letter to an intimate friend, EBB expresses no bitterness that her rival achieved the laureateship, but rather she communicates sincere and abundant appreciation for his art.

The second letter under examination also compares In Memoriam to another text, but in less glowing terms. This letter was written in 1871, twenty-one years after the poem’s publication, demonstrating its lasting relevance. In this letter, held in the Armstrong Browning Library’s Victorian Letters Collection, Irish literary critic and poet Edward Dowden writes to his former student (and future wife), Elizabeth Dickinson West, providing feedback on her essay and sharing a response to that essay from a “Mr. Grove.” He writes that Grove “praises your essay, & then finds faults with it, & does not on the whole see its real value I think.” Dowden’s description paints Mr. Grove as an opinionated individual, relating that Grove then goes off into criticism on his own account of Spenser whom he thinks commonly over-rated, of Tennyson & of Browning. He cannot agree with you in your comparison of Tennyson & Browning & thinks Tennyson addresses himself more effectively to the questions of the time than Browning. He says “I know Browning pretty well, & In Memoriam very well, & the latter has always been a fifth gospel to me.”

This account demonstrates that, even two decades after In Memoriam’s publication, it remained a standard of comparison for other texts. And Tennyson, as poet laureate, remained a standard of comparison for other poets, both current (Browning) and past (Spenser). Dowden firmly sides with West and her essay, critiquing Grove’s taste by noting, “Do you not know the kind of mind to which In Memoriam is a 5th gospel? Does not this give the measure of a man?”

The “Mr. Grove” Dowden mentions is Sir George Grove, secretary to the Crystal Palace and assistant editor of the literary periodical Macmillan’s Magazine at the time. Dowden was not the only critic of Grove’s sentiments, as “His character was complex” and some of his acquaintances “disliked Grove’s sentimentality” (Young). His colorful character paralleled his eclectic interests, which ranged from editing a musical dictionary, to contributing articles to William Smith’s Bible Dictionary, to enthusiasm for poetry—which, through his connections, led to friendship with and deep admiration for Tennyson. Grove’s first foray into literary criticism focused on Tennyson’s work, as Grove published two papers analyzing his poetry in 1866 in Macmillan’s Magazine. In the first of these papers, Grove compares Tennyson to Mozart and Beethoven, as he claims that Tennyson’s poetry presents “the same astonishing combination of beauty of subject and beauty of general form with perfect delicacy of detail, the same consummate art with the same exquisite concealment of it—and which, like it, form a whole that satisfies both the intellect and the imagination, and, once known, haunts the memory for ever” (Graves 137). Like the letters by EBB and Dowden, this paper shows that Tennyson tended to be juxtaposed with other artists—even musical rather than literary ones.

Given Grove’s reverence for Tennyson, it is little surprise that we find Dowden reporting that Grove said In Memoriam was a “fifth gospel” to him. Indeed, Grove’s own letters reveal that he expressed such a comparison more than once. In an 1865 letter to Miss M. E. von Glehn, Grove writes, “I hope soon to go and visit Tennyson and talk to him. A man who can write such a gospel as there is in In Memoriam—you know how I value that book—must know all about it, but where, I ask, did he get the art to build so vast and bright an edifice out of such slender materials and so gloomy a foundation?” (Graves 128) Grove’s comparison of In Memoriam to the gospel shows the spiritual and personal significance it held for an individual. However, Grove not only compares it to the gospel, but refers to it as “a gospel” here and “a fifth gospel” as related in Dowden’s letter. The letter demonstrates the heights to which In Memoriam was raised as well as an opposite tendency to turn up one’s nose at the poem. From Dowden’s repulsion and sarcastic response at Grove’s “fifth gospel” sentiment, we also see the skepticism of In Memoriam’s value.

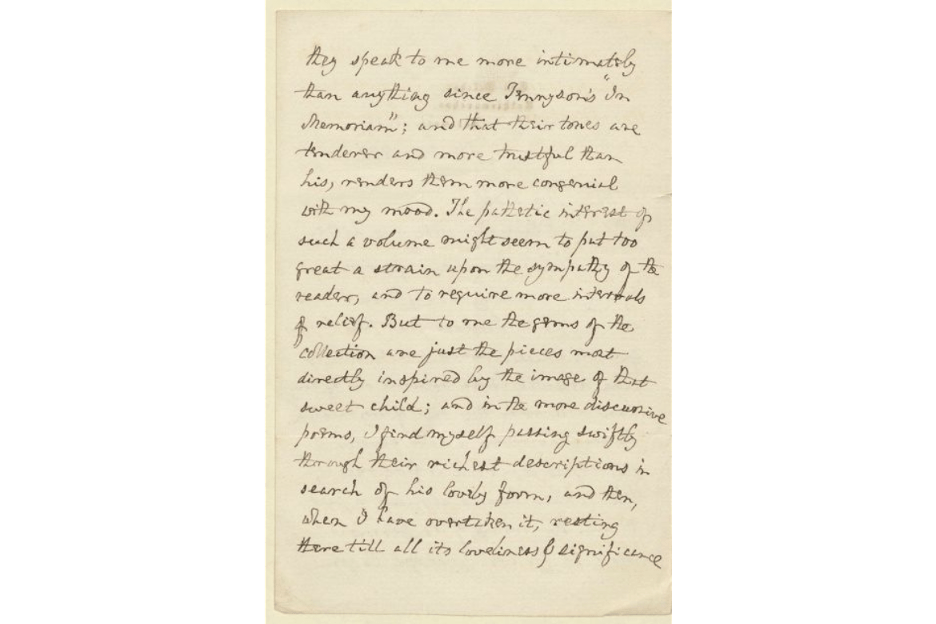

The third letter, also held in the Armstrong Browning Library’s Victorian Letters Collection, reveals the continued tendency to compare In Memoriam to other works three decades following its publication. However, in this case, the writer prefers another poet over Tennyson. In 1882, James Martineau, a Unitarian minister and respected religious philosopher (as well as the brother of novelist Harriet Martineau), wrote to Roden Noel to thank him for his collection of poems. Noel, a poet and essayist, wrote his volume of poetry, A Little Child’s Monument,in response to his five-year-old son Eric’s death. Among Noel’s work, this volume was the “best received and which remained most popular with his contemporaries” (Hinings). Martineau’s praise of the volume confirms this evaluation. He writes to Noel,

I brought with me hither your “Child’s Monument” . . . I have given myself to it; – read it & re-read it, – till it has become almost a part of me. For many of its poems I shall be for ever grateful to you: they speak to me more intimately than anything since Tennyson’s “In Memoriam”; and that their tones are tenderer and more trustful than his, renders them more congenial with my mood.

While suggesting that In Memoriam spoke to him “intimately,” Martineau also expresses the limits of the poem’s depth of feeling. Because Martineau also lost a child, his first-born Helen Elizabeth (Waller), he found Noel’s volume “more congenial with my mood.” He writes, “It is partly, no doubt, an experience similar to your own, that determines my preference for those: but in some degree also their greater ease and simplicity, which commands them to the literary taste of an old man habituated to the Wordsworthian level of English style.” Martineau was seventy-seven years old when he wrote this letter, thus his reference to himself as an “old man.” By showing his preference for Noel’s poetry, Martineau reveals that, although In Memoriam was still a standard of comparison, it occasionally did not emerge as the clearly preferred winner.[3]

Throughout each of these letters, it is clear that In Memoriam spoke to a variety of individuals over multiple decades, lasting in both its depth of feeling and its inspiration to compare. Tennyson himself said of In Memoriam: “It is rather the cry of the whole human race than mine. In the poem altogether private grief swells out into thought of, and hope for, the whole world” (Knowles 12). An examination of a poem’s reception like this one presents potential pedagogical implications for literature teachers. First, examining such letters shows that In Memoriam was not accepted uncritically, but that Tennyson’s contemporaries both praised and expressed skepticism about the poem that preceded his appointment as poet laureate. In addition, a valuable exercise in a class studying In Memoriam could involve comparing passages with those of A Little Child’s Monument.[4] As both poets dealt with death—one in a more personal way and one in with more universal implications—examining Tennyson and Noel side by side could emphasize how Tennyson’s project deviated from other memorial poetry of the era.

Works Cited

Browning, Elizabeth Barrett. Letter to Mary Russell Mitford. 15 June 1850. The Armstrong Browning Library Browning Letters Digital Collection. ab-letters-ltr_50035-00 Margaret Clapp Library, Special Collections, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/14-15-june-1850.-browning-elizabeth-barrett-to-mitford-mary-russell./348275?item=348278

—. Letter to Mary Russell Mitford. 13 December 1850. The Armstrong Browning Library Browning Letters Digital Collection. ab-letters-ltr_50066-00, Margaret Clapp Library, Special Collections, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/13-december-1850.-browning-elizabeth-barrett-to-mitford-mary-russell./348301?item=348305

Dowden, Edward. Letter to Elizabeth Dickinson West. 19 July 1871. The Armstrong Browning Library Victorian Letters Collection. ab-vic-ltr_v18710719-01, Armstrong Browning Library, Baylor University, Waco, TX. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/19-july-1871.-dowden-edward-to-dowden-elizabeth-dickinson-west./213795?item=213797

Graves, Charles L. The Life & Letters of Sir George Grove, Hon. D.C.L. (Durham), Hon. LL.D. (Glasgow), Formerly Director of the Royal College of Music; by Charles L. Graves. The Macmillan company, 1903.

Gwynn, E. J., and Arthur Sherbo. “Dowden, Edward (1843–1913), literary scholar and poet.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 03. Oxford University Press. Date of access 16 Mar. 2022, https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-32882

Hinings, Jessica. “Noel, Roden Berkeley Wriothesley (1834–1894), poet and essayist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 25. Oxford University Press. Date of access 16 Mar. 2022, https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-20235

Knowles, James. “Aspects of Tennyson.: II. A Personal Reminiscence.” Littell’s Living Age (1844-1896), vol. 196, no. 2539, Feb 25, 1893, pp. 515. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.baylor.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/aspects-tennyson/docview/90392765/se-2?accountid=7014.

Martineau, James. Letter to Roden Noel. 25 September 1882. The Armstrong Browning Library Victorian Letters Collection. ab-vic-ltr_v18820925-01, Armstrong Browning Library, Baylor University, Waco, TX. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/25-september-1882.-martineau-james-to-noel-roden./217228?item=217232

“Search Correspondence | Brownings’ Correspondence.” Accessed November 23, 2022. https://www.browningscorrespondence.com/correspondence/search/.

Stone, Marjorie. “Browning [née Moulton Barrett], Elizabeth Barrett (1806–1861), poet and writer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 04. Oxford University Press. Date of access 16 Mar. 2022, https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-3711

Waller, Ralph. “Martineau, James (1805–1900), Unitarian minister.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 25. Oxford University Press. Date of access 16 Mar. 2022, https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-18229

Young, Percy M. “Grove, Sir George (1820–1900), writer on music and lexicographer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 22. Oxford University Press. Date of access 16 Mar. 2022, https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-11680.

Notes:

[1] Letter numbers are provided as they appear in the online edition of the Brownings’ Correspondence, which can be accessed at https://www.browningscorrespondence.com/correspondence/search/.

[2] Stone does not mean this in an antagonistic or competitive sense, but that EBB rivaled Tennyson in popularity and recognition.

[3] It should be noted that Martineau’s focus seems more on the affective impact of these particular poems than on the respective merits of the poets or even the artistic qualities of the poems. The style and subject of Noel’s volume are made preferable to Martineau by his personal experience of losing a child.

[4] The passages from A Little Child’s Monument are available in the linked handout at the end of this document.