Autograph dedication of lines 313-315 of “Fra Lippo Lippi,” signed, in Robert Browning’s copy of The Ring and the Book (London, 1868-1869), dated Christmas Day, 1868, and later presented to J.D. Williams (Browning Guide E0142).

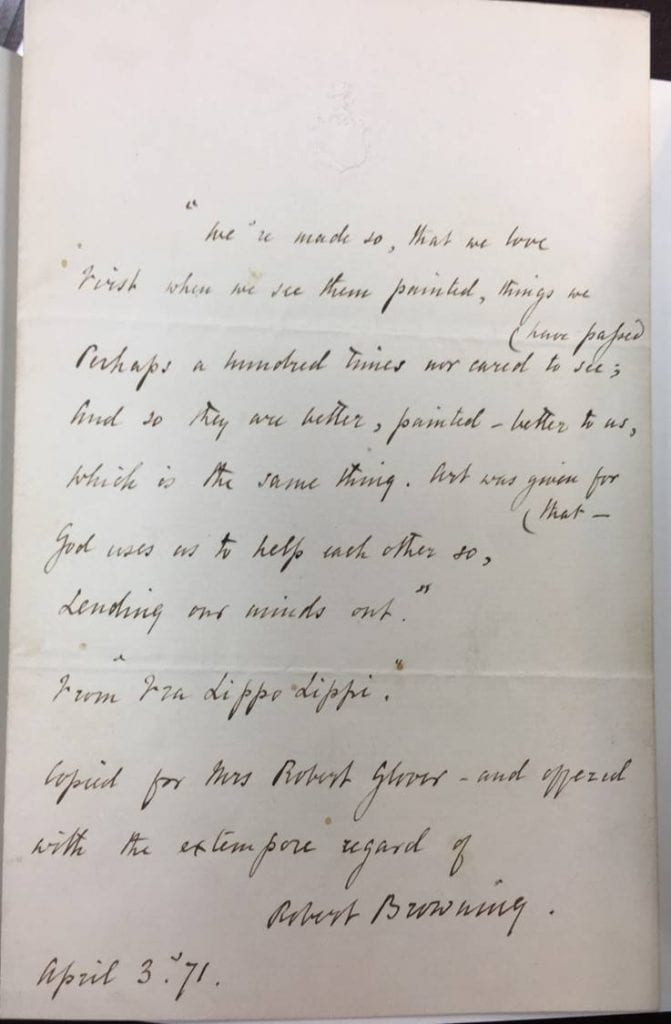

Autograph of lines 300-306 of “Fra Lippo Lippi,” signed, for Mrs. Robert Glover, dated April 3, 1871 (Armstrong Browning Library, Browning Guide E0141).

Rare Item Analysis: Blots and Blanks: Discussions of Artistic Depiction in The Ring and the Book and “Fra Lippo Lippi”

by Allison Scheidegger

Although Robert Browning’s 1868 The Ring and the Book enjoyed a far more positive reception than many of Browning’s earlier works, readers complained that Browning’s intense depictions of the lying murderer Guido blotted out the light of his wife Pompilia’s purity. Browning’s apparent zest in depicting sordid characters like Guido prompted the question, “Why invest so much creative power in depictions of evil?” (See Rachel Kilgore’s post for such an exchange between Browning and his friend and critic Julia Wedgwood.) In response, Browning insisted that his depictions of evil are both true to reality and essential to his poetic project. Reflecting this conviction, Browning the poet, a speaker in Book XII of The Ring and the Book, insists to the British public that “Art remains the one way possible / Of speaking truth, to mouths like mine at least” (845-6). Our rare items, an autograph dedication (Browning Guide E0142) and an autograph (Armstrong Browning Library, Browning Guide E0141) by Browning, draw lines from “Fra Lippo Lippi” which echo and inform the poet’s discussion of art’s vital function of oblique truth-telling.

“Fra Lippo Lippi,” a dramatic monologue appearing in Browning’s 1855 Men and Women, follows the wild speech of the fifteenth-century Florentine monk and painter Lippo Lippi, as he defends his Renaissance humanist theory of art. Against ascetic critics who argue that art should focus on the soul before the flesh, Lippo Lippi argues that when he paints the body well, he finds he has painted the soul accurately also. In The Ring and the Book, Browning the poet makes a similar statement, even comparing his work to that of a painter. Because art has the unique ability to convey truth indirectly, rendering it both more palatable and more effective for humans, poetry enables the poet to “paint [his] picture, twice show truth” (XII.862). Thus, Lippo Lippi and Browning the poet share the conviction that truth is best apprehended indirectly, through the forms of “flesh” and “fact.”

Working from this conviction, Lippo Lippi further asserts that both good and evil are legitimate subjects for depiction: “paint anyone [whether a beautiful woman or a scoundrel], and count it crime / To let a truth slip” (295-6). Two references to “Fra Lippo Lippi” around the time of the publication of The Ring and the Book suggest that Browning may have had Lippo Lippi’s defense in mind as he depicted the pure Pompilia and the base Guido. On Christmas Day, 1868, Browning inscribed lines 313-315 of “Fra Lippo Lippi” as an autograph dedication in his own recently-published first edition of The Ring and the Book (now held in the Wellesley College Library):

This world’s no blot for us,

Nor blank; it means intensely, and means good:

To find its meaning is my meat and drink.

Here, Lippo Lippi argues that the world is not a “blot,” to be censored and rejected as his opponents wish to, nor a “blank,” emptied of meaning and inviting the artist to impose his own meaning (313). Rather, the world, in all its mixture of good and evil, “means intensely” and ultimately “means good” (314). The work of the artist is to “find” this meaning. Positioning this invocation at the beginning of his copy of The Ring and the Book suggests that Browning may have been linking Lippo Lippi’s affirmation of the meaning of alleged “blots” with his concern in The Ring and the Book to show the ultimate good that came from Guido’s evil actions and ensuing murder trial. Just as for Lippo Lippi it would be a “crime” not to paint a “cullion’s [scoundrel’s] hanging face” (307), for Browning it would be a crime to smooth over or ignore any of Guido’s blackness.

Browning’s autograph of lines 300-306 of “Fra Lippo Lippi,” held at the Armstrong Browning Library, expands the shared theme of art’s truth-telling power. Written in Browning’s hand and dedicated to Mrs. Robert Glover, this autograph is dated “3 April ’71”—less than three years after the publication of The Ring and the Book.

…“we’re made so that we love

First when we see them painted, things we

have passed*

Perhaps a hundred times nor cared to see;

And so they are better, painted–better to us,

Which is the same thing. Art was given for

that–

God uses us to help each other so,

Lending our minds out.”

From “Fra Lippo Lippi.”

Copied for Mrs Robert Glover–and offered

With the extempore regard of

Robert Browning

April 3. ’71.

*[Due to space limitations, Browning inserted “have passed” and “that–” below their proper lines.]

Lippo Lippi wants his viewers first to notice “things [they] have passed” daily without caring to really see (301). All aspects of life, as Lippi has earlier established, are worthy of notice. Because human perception is imperfect, filtered, and indirect, Lippo Lippi says, things depicted artistically are “better to us, which is the same thing” (303-304). His clarification here emphasizes how art’s indirect representation so well suits human perceptions. While humans tend to overlook seemingly commonplace or unpleasant things, art redirects our vision to see them anew. And, Lippo Lippi says, true seeing leads to loving. Therefore, things are “better painted.”

This passage mirrors the poet’s discussion of art in Book XII even more closely. Anticipating readers’ objections, Browning the poet asks, “Why take the artistic way to prove so much?” His answer echoes and extends Lippo Lippi’s praise of art: “Because, it is the glory and good of Art, / That Art remains the one way possible / Of speaking truth, to mouths like mine at least” (843-6).Thus, because both human “minds” and human “mouths” are best designed to communicate and apprehend truth through art, the artist lends his mind and mouth for this purpose. Similarly, because art is indirect, or “missing the mediate word,” as the poet later says, it works so well with humans’ imperfect apprehension, and thus “twice show[s] truth” (862).

Through its oblique representation of truth, Browning the poet and Lippo Lippi agree, art has the power to make the world “better.” Browning the poet argues that

…Art may tell a truth

Obliquely, do the thing shall breed the thought,

Nor wrong the thought, missing the mediate word.

So may you paint your picture, twice show truth,

Beyond mere imagery on the wall, —

…

So write a book shall mean, beyond the facts,

Suffice the eye and save the soul beside. (859-67)

The poet’s goal to “write a book [which] shall mean, beyond the facts” gains greater significance within the framing context of “Fra Lippo Lippi,” where the apparent “blots” of the world “mean intensely” and challenge the artist to find their meaning. The artist’s oblique access to the truth is won through what Lippo Lippi calls “noticing” and “loving”—by carefully depicting both good and evil rather than omitting “blots” or reducing life to a “blank,” artists are “lending [their] minds out” and being used by God to help their fellow men (305-6). The poet illustrates this divine purpose, pointing out that whereas direct truth-telling often angers, hardens, and disappoints hearers, art can open blind eyes and stopped ears (847-57). By forcing humans to experience truth which they would reject as offensive if presented directly as a judgment or axiom, a story enables readers to productively struggle with the good and evil in the world, and thereby progress toward loving the truth. Therefore, art is not only the most effective way to access truth, but is even potentially redemptive. The poet similarly hopes that his book will “do the thing shall breed the thought” (860), drawing readers’ attention not only to the beauty and light in the world, but also to the real evil in characters like Guido—and even in themselves. Thus art has power even to “save the soul,” as, for example, the “thought” or recognition bred by art may in turn lead to repentance.

Although it is tempting to interpret Browning’s two selections from “Fra Lippo Lippi” as authorized expressions of his own artistic mantra, Browning vehemently resisted readers’ tendencies to identify dramatic monologues as expressions of his own thought.[1] In his preface to the 1842 Dramatic Lyrics, Browning asserted that his dramatic monologues were “always Dramatic in principle, and so many utterances of so many imaginary persons, not mine” (“Advertisement”). This distinction, however, does not undermine the shared theme of art’s truth-telling potential in “Fra Lippo Lippi” and The Ring and the Book. In fact, by exploring this theme through the expressions of diverse characters, Browning illustrates the very function of art that his characters discuss. Refusing to hand his readers an artistic mantra, he instead chooses to place a seeming echo of his statements in the mouth of a lecherous artist who expresses other perspectives that Browning certainly did not share. In The Ring and the Book, Browning increases the indirectness of his dramatic monologue form by presenting multiple conflicting testimonies on Guido and Pompilia. By doing this, Browning highlights what he sees as the power of art: to reenact and give form to the jumble of lies, prejudice, dubious facts, and incomplete knowledge which render truth so elusive. In this choice, as well as in his self-dramatization as “Browning the poet” in The Ring and the Book, Browning is enacting the mission of the artist, offering his audience the chance to encounter and untangle the messy truth.

Taken in conjunction with the echoes of “Fra Lippo Lippi” in the poet’s speech in Book XII, Browning’s two allusions to “Fra Lippo Lippi” around the time of the publication of The Ring and the Book suggest that Browning saw his project as an attempt to find meaning in a world often dismissed as a blot or blank.[2] With this in mind, he introduced his readers to a murder trial and its myriad of speakers and motives, issuing readers an invitation to grapple with good and evil, and “not let a truth slip.” We, Browning’s modern-day reading public, can benefit from wrestling with the combined testimonies of Lippo Lippi and Browning the poet as we search for truth in a public sphere increasingly characterized by conflicting perspectives. Affirming that the struggle for truth is worthwhile, these two speakers praise art, with its capacity for indirect depiction, as a uniquely productive way to help humans interact with the world meaningfully and lovingly. Moreover, experiencing Browning’s artistic theory through this dialogue of poems can enrich our understanding and appreciation of Browning’s other art-themed dramatic monologues, particularly the troubled artist monologues such as “Andrea del Sarto” and “Abt Vogler.”

Click here to visit an interactive timeline and map related to this post on Central Online Victorian Educator (COVE).

Works Cited

Browning, Robert. “Advertisement.” The Poetical Works of Robert Browning, vol. 3: Bells and Pomegranates I–VI: including Pippa Passes and Dramatic Lyrics, edited by Ian Jack and Rowena Fowler, Oxford UP, 1988, www-oxfordscholarlyeditions-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/view/10.1093/actrade/9780198127628.book.1/actrade-9780198127628-div2-11.

—. “Fra Lippo Lippi.” The Poetical Works of Robert Browning, vol. 5: Men and Women, edited by Ian Jack and Robert Inglesfield, Oxford UP, 1995, www-oxfordscholarlyeditions-com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/view/10.1093/actrade/9780198127901.book.1/actrade-9780198127901-div2-14.

—. The Ring and the Book, edited by Thomas J. Collins and Richard D. Altick, Broadview Press, 2001.

[1] Further, at least in the case of the autograph, it is unknown whether Browning chose the lines himself or copied the lines at Mrs. Glover’s request.

[2] Browning’s epistolary discussion of his poetic project in The Ring and the Book offers yet another dimension to Lippo Lippi and the poet’s shared concern with the artistic depiction of good and evil. In his letter of 19 November 1868 to Julia Wedgwood, Browning compares himself to a painter concerned with both precision and finding meaning:

[my] business has been, as I specify, to explain fact…the black is so much,—the white, no more. I have made the most of every whitish tint in the things texture: and as, when Northcote asked Reynolds why he put no red into his flesh, looked awhile earnestly at his own hand and then replied, “I see no red here”—so I say, “I see no more white than I give.” But remember, first that this is God’s world, as he made it for reasons of his own, and that to change its conditions is not to account for them—as you will presently find me try to do.