Browning, Robert The Ring and the Book. 2nded, vol. 1-4, London, 1872. § Contains numerous corrections by RB. Browning Guide: A0475

Rare Item Analysis: Alterations between the 2ndEdition of The Ring and Book and Markings Found in Browning’s Personal Copy of Book Nine, Circa 1888

By Mason McLain

COVE timeline | COVE timeline entry | COVE map

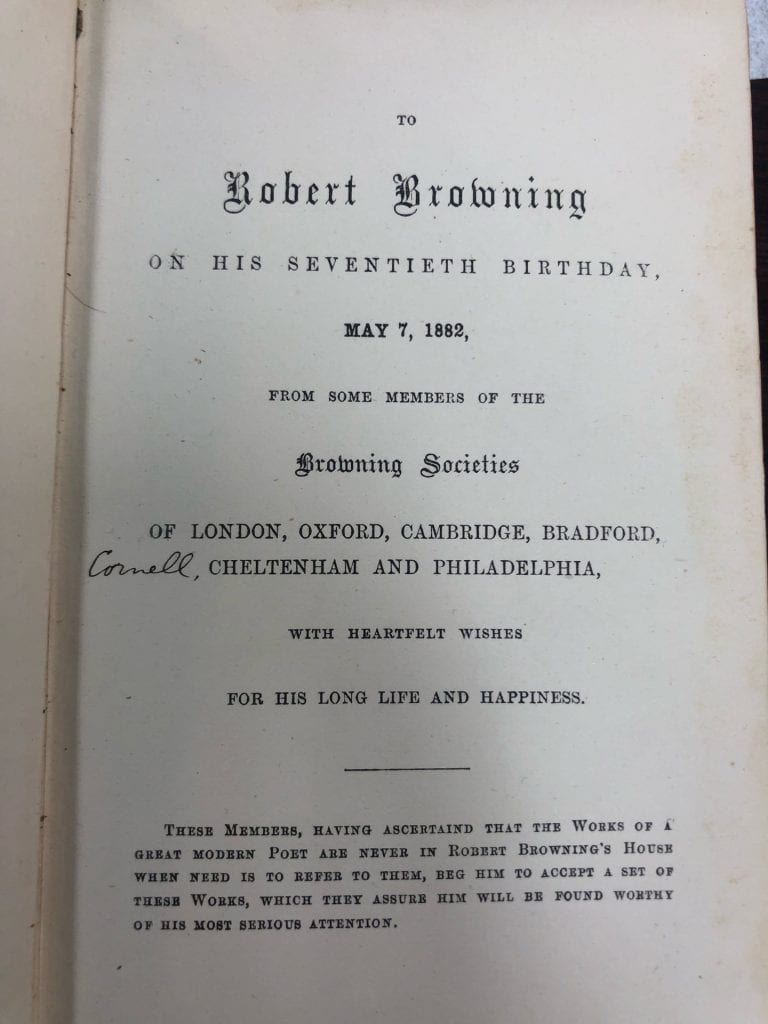

The Armstrong Browning Library houses a plethora of rare artifacts relating to Robert and Elizabeth Browning, including a second edition copy of The Ring and the Book, first published in 1872, that waspersonally owned by Robert Browning. Known to many as his greatest work, The Ring and The Book was published originally in 1868 in London by Smith, Elder & Co. The beautiful four-volume set of books found at the ABL was printed in 1872 and gifted to Robert from the Browning Societies in 1882. This piece stands quite exceptional because Browning makes hundreds of various annotations, corrections and additions in the copy present at the ABL. The volumes illuminate the mind of Browning in how he continues editing the 21,000-line masterpiece fourteen years after its original publication and ten years following the second. Browning was seventy years old when the Browning Societies sent him the copy with an addition inscribed on the title page saying, “These members, having ascertained that the Works of a great modern poet are never in Robert Browning’s House when need is to refer to them, beg him to accept a set of these Works, which they assure him will be found worthy of his most serious attention” (see the image at the end of this post). For another perspective on this rare item, see Aaron Cassidy’s post, “A Gift Rediscovered: Robert Browning’s Revised The Ring and the Book.”

The plot revolves around the murder trial of Count Guido Franceschini for the murder of his wife Pompilia Camparini.The book details the account of the impoverished nobleman attempting to manipulate the 17thcentury Italian judicial system, and is told through a series of monologues by different characters connected to the events. The story of which Browning creates his tale stems from an actual trial set in Rome in 1698. Guido and his four partisans were tried and convicted of murder.

Interestingly, Count Guido is the only character in The Ring and The Book who is given two separate instances to speak, Book V and Book XI. Book V entails Guido’s attempt to use his social class, high speech, and artifice to manipulate the court to escape the clutches of damnation. He pleads incessantly to no avail and then appeals to the “higher court” or the Church. My research focuses on the analysis of Guido’s second monologue (Book XI) set in the prison cell following the denial of absolution by Pope Innocent XII in Book X. The various notations and additions found in the artifact attest to the mindset and personality of Browning and reveal a more vivid conception of the characters, such as Count Guido Franceschini.

Browning stumbled upon what would be known as The Old Yellow Bookon the Piazza di San Lorenzo in June of 1860. The weathered account of Guido’s homicide and related trials became the basis for his narrative verse utilizing the poetic form of dramatic monologue, the medium he mastered over the twenty-five years prior. The Old Yellow Book would remain in Browning’s personal library in London alongside the 2nd Edition personal copy of Robert’s The Ring and The Book (A0475) located in the Browning Collection at the Armstrong Browning Library found on Baylor University’s campus. Through analyzing this one-of-a-kind book, we are able to have a greater understanding of who Browning was, notice differences between the 2nd edition, Browning’s personal copy, the 1899 edition, and see how these alterations work in cohesion to portray Guido more fully.

Browning seems to have three main motives behind editing his personal copy: first, to increase the fluidity between the lines signified by the omission of commas and their replacement with dashes; second to alter subjects and verbs to clarify meaning; third, to add adjectives to sharpen the image of his characters.

Browning makes little adjustment in his personal copy between lines 1-950 of Book XI with only a few notable differences. On line 116 he changes the word “apprize” to “apprise” evolving a more archaic spelling of the word. The period closing line 194 is edited to a dash to connect and flow the adjoining lines. The word “nor” becomes “not” on line 344, and he adds an exclamation mark to the close of 845.

|

1872 Second Edition (Browning’s Personal Copy, Received 1882) Oh, it had been a desperate game, but game Where in the winner’s chance were worth the pains We’d try conclusions! – (844-846) |

Passage Rewritten with Browning’s Changes Oh, it had been a desperate game, but game Where in the winner’s chance worth the pains! We’d try conclusions! – (844-846)

|

This edit turns one exclamatory phrase into two separate exclamations, which in turn lends greater urgency to Guido’s tone. If we look closely at lines 953-958, they reveal a much greater alteration.

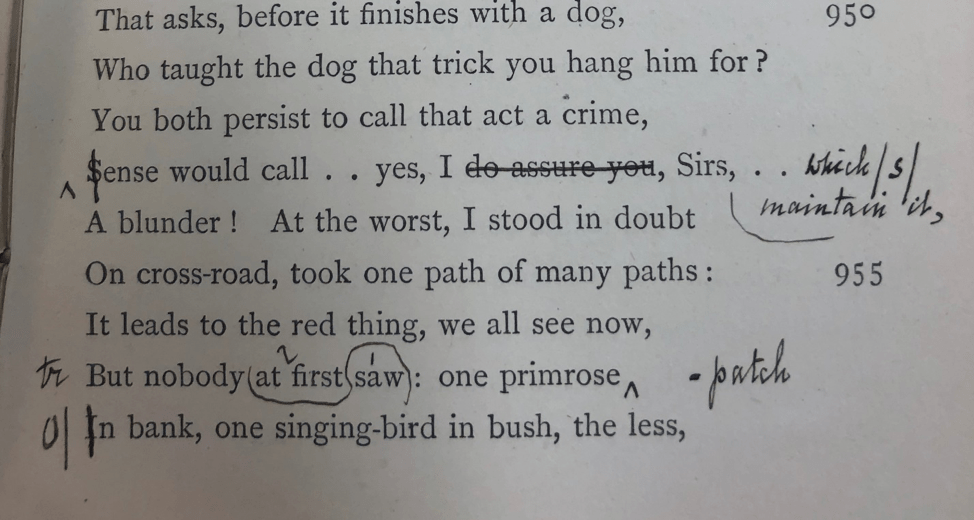

Fig. 1. Robert Browning’s Personal 2nd Edition Copy Gifted by the Browning Societies. Photo by Mason McLain.

Notice on line 953 Robert strikes through “Sense” and in the margin he adds an insertion mark connotating his intent to begin the sentence with “Which sense.” He crosses out “do assure you” and replaces the segment with “maintain it.” At this point in Guido’s monologue, he denies that killing Pompilia should be considered a crime and refutes his peers and the Pope’s judgment by calling their mindset a “blunder.” How do Browning’s notations bring clarity to the narrative as well as better the flow of the passage? By striking out “do assure you” he removes four syllables from the line, and by replacing the phrase with “maintain it” he is still one syllable shy of a full line of pentameter. So, by adding “Which,” he replaces the syllable removed, therefore evening out the line. How does the phrase “maintain it” shape the monologue? It clarifies Browning’s intended characterization of Guido, who has “maintained” that referring to his killing of Pompilia as a murder is invalid. By using the word maintain, Browning intends for Guido’s monologue to seem solidified with his prior statements, or his character intends for his audience to believe he has maintained his guiltlessness. “I do assure you” could connotate this was the first time he iterates his innocence, but we see evidence of aged Browning bringing cohesion to the narrative of Guido by a simple change, evident in line 953. Notably, Browning flips “at first saw” into “saw at first” on line 957 to ease the flow of words and adds patch to primrose to make “primrose patch” a more vivid idea. Did Browning’s notations found in his personal copy at the ABL honestly have any lasting effects or were his edits lost to history? If we look at an 1899 edition by Houghton and Mifflin (first published in 1890), we can find the answer.

1899 Edition Houghton, Mifflin

Which sense would call . . . yes, I maintain it, Sirs, . .

A blunder ! At the worst, I stood in doubt

On cross-road, took one path of many paths:

It leads to the red thing, we all see now,

But nobody saw at first : one primrose-patch

In bank, one singing-bird in bush, the less. (953-958)

The rare artifact found at the ABL indeed testifies to the mind of Robert Browning in how he incessantly altered his work toward perfection. Even at seventy years old and unbeknownst to him, nearing death, he was still tirelessly editing. His keen eye and attention to detail can be seen through the manifestations of the notations found. The alterations did, in fact, matter and change the evolution of The Ring and The Book by bringing clarity and vivacity to each character’s monologue, especially Count Guido. Instances such as the phrase changes in line 953 show us how the great poet is always changing, removing, adding, and most importantly, thinking about his work, and how the gracious gift, a leather-bound second edition copy of his own masterpiece would, in fact, alter history! The artifact would be a great item for research for anyone looking to study the evolution of Browning’s writing process. The rare piece cannot be found anywhere else, and it represents the continuous work of the great poet. Perhaps it could be a biographical primary source to anyone writing a thorough analysis on the transition between first and second editions and the Houghton & Mifflin or later publications. Comparing editions of the same work is a great way to develop our own writing ability and shows us how even the greatest literary minds did not write perfectly on their first try. The personal copy represents how writing is a living, breathing thing, which continuously grows and develops.

Works Cited

Browning, Robert. The Ring and The Book. 2nd ed., vol. 1-4 4, Smith, Elder and Co, London, 1872.

Browning, Robert. The Ring and The Book. Vol. 1-4, Houghton & Mifflin, Boston, 1899.