The Liberty Bell. American Anti-Slavery Society, 1848 containing the first appearance of EBB’s “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” ABLibrary Rare X 326 C4661 1848

Browning, Elizabeth Barrett. Poems Chapman & Hall, 1850. ABLibrary Rare X 821.82 L C466p

Rare Item Analysis: Elizabeth Barrett Browning Crafts a Comparison that Pushes the Envelope in order to Open the Eyes of her Audience

By Destiny Reynolds

COVE timeline | COVE timeline entry | COVE map

Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote many works that challenged the mindset and norms of people by making them aware of the discrimination and the abuse that some marginalized groups, like slaves and children, were enduring. This post focuses on two rare items, Poems (1850) and The Liberty Bell(1848), which both hold edited versions of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem, “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point.” Both of these books can be found at the Armstrong Browning Library in the Rare Books Collection. Both embody Browning’s jarring and eye-opening poetry as well as her careful consideration of placement and wording for her works.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was very famous at this time in England for other works that she had done. She refreshingly uses her fame in order to bring the conversation about slavery in the American Colonies to light. Her poem “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” is set at Plymouth, Massachusetts where the Pilgrims first landed (Pilgrim’s Point), and a runaway slave woman is telling about how she escaped slavery. She ran to freedom and recounts all of the abuse she received, horrifically telling the reader that she felt she had no choice but to kill the child produced from her rape by a white man overseeing her. She mentions the child having skin too fair and a face with “[t]he master’s look that used to fall / On my soul like his lash” (144-145). The runaway slave strongly expresses her distress at being reminded of her abuse by caring for a child produced by violence. She has to become callous in order to get past her trauma, and in doing so, she distances her self from her own child, rationalizing his killing. There are two versions of the poem, “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” in two different collections. The first time the poem was published was in The Liberty Bell in 1848. Browning completed and published this poem about 10 years after the Emancipation Act of 1833, which ended slavery and the slave trade in England. This poem’s publication in 1848 may have been Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s way of reminding people in England that the New England colonies were still participating in slavery and benefiting financially from the labor of slaves. In “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point,” Browning gives a shocking example of the psychological distress that slaves suffered in New England. Browning was using an emotional appeal in order to get her audience to think about the atrocities that were going on in New England. This conviction motivated Browning to publish the poem in TheLiberty Bell, which was published in Boston for an American audience and was meant to raise awareness and financial support for abolition of slavery in the United States.

Later Elizabeth Barrett Browning published a slightly altered version of “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” in 1850 in her own collection called Poems. Browning uses this poem once again to bring awareness to issues in the community but for this time a slightly different but still familiar issue. “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” is republished the same year that a group that fought for the rights of the working people was overran by the government. This group was the Chartist Movement. This movement was put in place to speak out for working people and child laborers who were often taken advantage of and overworked. The English government suppressed the Chartists. Some of the changes that Browning makes from her 1848 version to her 1850 version of “The Runway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” highlight the similarities between slavery in America and child laborers under minimal labor laws in England. She changes a few of the stanzas and the wording of “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” to be more similar to her other poem “The Cry of the Children.” “The Cry of the Children” talks about the woes of children laborers and how abandoned they feel. Browning is bringing in an emotional appeal, arguing that children should be able to live like children instead of working so much. When the government overthrew the Chartist Movement, many believed the government was not willing to look out for the working class and children laborers. The comparisons that Browning creates in the two poems relate the child laborers to slaves.

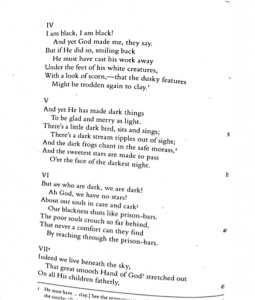

Browning changes a few stanzas of “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” between the 1848 version published in The Liberty Bell and the 1850 version published in Poems. These edits as well as the placement of the poem in amongst the other poems in Poems make “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” more similar to “The Cry of the Children.” These changes illustrate the parallel Browning is drawing between slaves in America and the children laborers in England, an atrocity still prevalent at the time of the 1850 republication. Browning made several small changes to words throughout the poem, but there is also an example of a complete stanza that is added to “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” that draws connections to “The Cry of the Children.” The addition of stanza seven brings in the idea that God is there for us all like a father to his children, and a very similar idea appears in “The Cry of the Children.” For example:

Indeed, we live beneath the sky, . . .

That great smooth Hand of God, stretched out

On all His children fatherly,

To bless them from the fear and doubt,

Which would be, if, from this low place,

All opened straight up to His face

Into the grand eternity (“The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point 43-49)

…We know no other words, except ‘Our Father,’

And we think that, in some pause of angels’ song,

God may pluck them with the silence sweet to gather,

And hold both within His right hand which is strong.

‘Our Father !’ If He heard us, He would surely

(For they call Him good and mild)

Answer, smiling down the steep world very purely,

‘Come and rest with me, my child.’ (“The Cry of the Children” 117-124)

The image of God being a father-figure appears in both “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” and “The Cry of the Children.” The speakers in each state that God is a father-figure, but the children and the slave woman both reveal that they may not truly believe that God is really there for their well-being. For example:

“But, no !” say the children, weeping faster,

” He is speechless as a stone ;

And they tell us, of His image is the master

Who commands us to work on. (“The Cry of the Children” 125-128)

I am black, I am black;

And yet God made me, they say.

But if He did so, smiling back

He must have cast His work away

Under the feet of His white creatures,

With a look of scorn,–that the dusky features

Might be trodden again to clay. (“The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” 22-28)

The lines from both poems draw very similar conclusions: God was not there for them but was actually present for the white men who were overseeing and controlling them. The addition of stanza seven in “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” really makes that comparison easier to see. There are further instances in the poems when both of the groups, the children and the slave woman, felt like they were being treated unfairly. One example is the children saying they are so tired that they can not even play. Another instance is when the slave woman is so traumatized that when she meets her lover she does not even know if they should be allowed to see each other in a loving way. In both of these examples, the speakers cannot do what they ought to be able to do. It is strange that a child would be so tired from working that it could not play in a field as children do. Similarly, lovers should not feel so afraid that they aren’t comfortable to fall in love with each other. These two poems elicit the same empathy for the children and for the slave woman. The similarities between these two poems and the convenience of them being so close in proximity, leads to the biggest change. Browning changes the placement of these two poems from her 1848 version to her 1850 version, placing “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” and “The Cry of the Children” right next to each other. Anyone reading the 1850 Poemsversion would be able to see the comparison she is drawing between these two poems and the overall similar emotion that they both portray. Having them right next to each other would have portrayed the message to the reader that there is a similarity between the slave woman and the children, due to all of the similar voices in the poems.

These two rare books from the Armstrong Browning Library were fantastic to compare. They really portrayed the way that Elizabeth Barrett Browning was trying to open up the eyes of her audience and make them aware of the abuse that the marginalized were facing. She crafted her poetry in order to entertain the audience but also pulled on their emotional strings in order to make sure that they were being empathetic to the two groups. The collection Poemsis a perfect example of Browning’s craft. She chooses to go a step further with this 1850 publication by drawing the comparison of child laborers to slavery. She crafts this comparison to make her audience aware that they are not safe from scrutiny when they had, at that time, modern-day slavery in children. The comparison of the two books that she specifically crafts pushes the envelope and makes sure that her audience, English people, are not ignorant to the injustices that were right in their backyard. These two items in the ABL can be used in the future by other scholars to remind our audiences that there are different forms of injustices and modern-day slavery. When thinking of today’s audience we can use these items to draw comparisons to the way we treat certain groups and ways that we may be treating them unjustly, like modern-day for-profit prisons, forcing people to labor for nearly no income, which could be considered a cruel and unusual punishment. The items could be used by scholars who are trying draw comparisons to injustices still happening today.

1848 Version

1850 Version