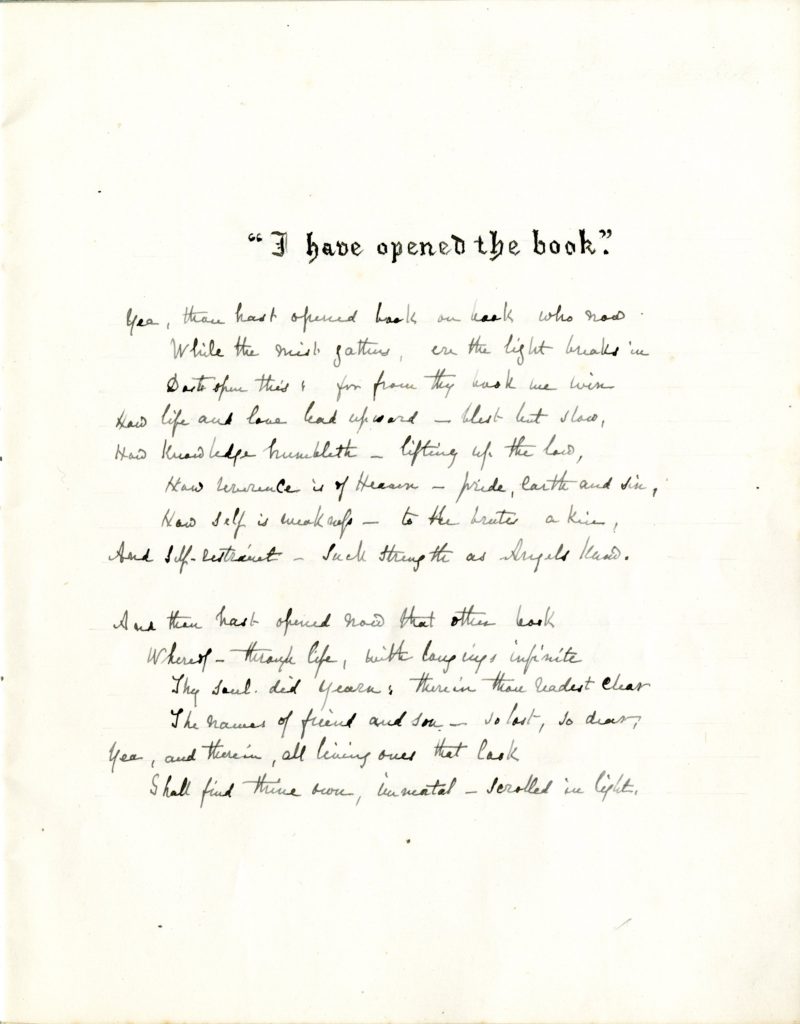

This is a handwritten transcription by Frederick Tennyson of a booklet of sonnets and other materials on the death of Alfred, Lord Tennyson penned originally by Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley and entitled “The Death of the Laureate Alfred Lord Tennyson.” Victorian Letters Collection ID: V892100601 Location.

Rare Item Analysis: Elegiac Memorializing of Tennyson as Prophet

by Clayton McReynolds

The Armstrong Browning Library at Baylor University holds a variety of items pertaining to Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poetic and personal life. One of these items is a slim packet of elegiac sonnets and other material related to Tennyson’s funeral, which was held on October 12, 1892. This packet was assembled by Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley (1851-1920), and it sheds light particularly on the poet’s passing and the ways in which the lauded laureate was committed to memory. Rawnsley’s booklet, which is held in the Victorian Letters Collection, includes an excerpt from one of Hallam Tennyson’s letters concerning his father’s death; five original sonnets penned by Rawnsley himself; a hymn for the funeral written by Rawnsley’s wife Edith Rawnsley (1846-1916); and a description and photograph of the pall for Tennyson’s funeral. Rawnsley was an Anglican priest, a prolific poet and writer, and one of the foremost founders of the National Trust. He was acquainted with Tennyson both through their joint efforts in conserving the Lake District and through a longstanding friendship between his family and the Tennysons (Hardwicke Drummond’s father conducted the marriage service of Alfred Tennyson and Emily Selwood).

This particular manuscript, however, is not the original booklet believed to have been penned by Rawnsley but rather a transcription by Frederick Tennyson (1807-1898) of that original. According to an inscription on the first page of the booklet, Frederick, the elder brother of Alfred, copied the poems with the permission of Rawnsley and sent the packet in its entirety to one Mary Williams on February 7, 1893. All of the materials in the booklet seem to be in Frederick’s hand, and the title page attributes the pamphlet as a whole to H.D. Rawnsley, so it appears that Frederick copied not only the poems but the manuscript as a whole from a similar pamphlet created by Rawnsley. It is unknown who Mary Williams was or why Frederick took a particular interest in sending the contents of the booklet to her. At a later period in 1893, Rawnsley published Valete: Tennyson and Other Memorial Poems, a collection of elegiac poetry, including revised versions of each of the five sonnets in this packet along with several other poems mourning Tennyson and other public figures. Prior to either Frederick’s penning of this pamphlet or the publication of Valete, the sonnet “The Laureate Dead” was published in The Academy: A Weekly Review of Literature, Science, and Art only seven days after Tennyson’s funeral. The same sonnet was republished in Little’s Living Age on December 7 of that same year and again in the American Magazine of Poetry later in 1893. A sonnet by Rawnsley entitled “Leaving Aldworth” was also published in November 1892 in Blackwood’s Edinburg Review, but despite sharing the subject matter and certain images in common with the sonnet of that title in this booklet, it appears to be, in essence, a different poem. Each of the contents in this packet provide intriguing insight into ways that Tennyson was memorialized during and after his death by his contemporaries. In particular, Rawnsley’s sonnets, by drawing on particular poetic works of Tennyson to exemplify the gravity of the laureate’s passing, reveal much about how Rawnsley understood Tennyson’s role as the revitalizer and perhaps even re-creator of Christian religion in Victorian England.

Rawnsley depicts Tennyson as not just any spiritual guide but as a spiritual guide particularly to the English people, and Tennyson’s centrality to England is made clear throughout the sonnets. In “The Laureate Dead,” for instance, Rawnsley describes how Tennyson wrote “with Saxon purity of tongue” (12). In the same sonnet, Rawnsley sets Tennyson next to Shakespeare and casts him as an epic poet for England in the same way Homer was for Greece, and in “Tennyson’s Homegoing” he orders that the laureate’s pall be “strewn with English roses” (4). Reinforcing this idea of Tennyson as essentially linked to the English nation is, of course, his role as Poet Laureate which is brought to the fore in each sonnet. Rawnsley must have written “The Laureate Dead” within the week of Tennyson’s funeral since it was published in The Academy only seven days after that event, and he dated that sonnet (a bit implausibly) October 6, which was the actual day of Tennyson’s death, six days before the funeral itself. The other sonnets were similarly indicated to have been penned concurrently with or immediately after the funeral, which casts them as organic responses in the immediate wake of Tennyson’s loss. Their function in expressing a collective grief for that loss is indicated in the way that “The Laureate Dead” was published in each of its magazine appearances always before further poems elegizing Tennyson and usually before a lengthy obituary for the laureate. A clear testament to Rawnsley’s understanding of Tennyson’s deep connection with the English people can be seen in Memories of the Tennysons, a biographical work written by Rawnsley and published in 1912, where he declares of Tennyson:

But to those few of us who were born under his star and were contemporaries of his prime, he was literally the poet par excellence, and of right divine. And surely he was our one great English poet—living so English, thinking so English, dying so English…Tennyson has set England before our eyes, he was the interpreter of our feelings—the prophet, if not of our creed, of our faith. (289)

Here, Rawnsley describes Tennyson as giving voice to the shared spiritual experience of his fellow Englishmen, and in these elegiac sonnets he reveals that Tennyson also played a central role in shaping those feelings to which he gave voice. At the same time, however, Rawnsley accedes that Tennyson’s role was not to reinforce specific dogma of traditional belief but instead to communicate the process of spiritual belief more broadly. This recognition points to the way that Rawnsley, despite occasionally casting Tennyson in a more traditionally religious light, generally identifies the conjunction of Tennyson’s doubt and his faith as the quality that enabled him to act as the spiritual mouthpiece for his age and for England.

Rawnsley portrays Tennyson’s service as spiritual guide for the nation most often through images of song and voice. In “Christmas Without the Laureate,” he mourns the death of Tennyson, declaring, “our voice has failed!” (5). Thus, Rawnsley suggests that Tennyson spoke for the nation collectively, and he reiterates this theme in “Tennyson’s Homegoing” where he describes the London lanes as “The roaring streets that felt within their roar/ His psalm of grace” (11-12). Here again, Rawnsley depicts Tennyson as both speaking for the people and into the people, molding their voice and giving expression to it simultaneously through his song. The most striking statement about the concrete effect of this influence is found in “Christmas Without the Laureate” where Rawnsley praises Tennyson as he who “sang two generations back to Christ” (13). This tells us clearly what Rawnsley understood the most essential import of Tennyson’s much-lauded song to be. It is through his song that Tennyson served as the “prophet” of the English people’s spiritual faith, uniting the people around that faith by simultaneously creating and expressing the voice of the nation through his own song.

That “song,” of course, was Tennyson’s poetry, and Rawnsley assigns especial significance to certain of Tennyson’s poetic accomplishments, holding them up as preeminent tools through which Tennyson reconstituted a unifying Christian vision. While all of the five sonnets in this booklet portray Tennyson as central to the nation’s spiritual identity, it is chiefly the second sonnet, “The Laureate Dead,” and the final sonnet, “Christmas Without the Laureate,” that identify particular poems of Tennyson as instrumental in forming that identity. The final lines of “The Laureate Dead” ask mournfully:

But when shall sing another as he sung

Who wrought with Saxon purity of tongue

The one great epic of two hundred years,

The one memorial utterance for all time? (11-14)

While addressing Rawnsley’s stated question would be a difficult undertaking, we might content ourselves by treating merely the derivative question of what accomplishments of Tennyson he is referring to here. What are respectively “the one great epic” and the “one memorial utterance”? Certainly the most intuitive conclusion is that the “epic” is Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (1842-1888) and the “memorial” is his famous elegy In Memoriam (1850), and an examination of Rawnsley’s sonnets strongly supports that conclusion. The Idylls and In Memoriam are by far the most alluded to Tennyson poems in the sonnets, with a couple explicit appeals being made to the former and even more allusions being made to the latter.

There are two direct mentions of the Idylls in Rawnsley’s sonnets. The first occurs in “The Laureate Dead,” the same poem wherein Rawnsley mentions Tennyson’s “great epic.” In the octave of that sonnet, Rawnsley expounds upon the greatness of Tennyson, painting him as a poet equal to Shakespeare and to Homer in terms both of literary merit and cultural import. In the seventh line, he praises Tennyson as the one “Who gave us back the old Arthurian days” (7). Clearly, Rawnsley is identifying the Idylls and perhaps “Morte D’Arthur” here as seminal accomplishments in Tennyson’s career, but a further examination of the sonnets reveals that Rawnsley is actually claiming much more. The first indication of this comes in the ninth line of the same sonnet, when Rawnsley follows the news of Tennyson’s departure by stating: “Our golden age is shorter” (9). This language appeals to Homer, whose epic poems look back to a golden age, to the swift but glorious endurance of Arthur’s Camelot, and to England’s literary golden age when Shakespeare penned his masterpieces. However, the specific golden age it refers to is neither Homer’s nor Arthur’s nor Shakespeare’s but a new golden age presided over by Tennyson and fading away with him. The precise nature of this golden age, achieved in part through Tennyson’s resurrection of the Arthurian days, is clarified in “Christmas Without the Laureate” where, in the midst of lines alluding to In Memoriam, Rawnsley describes Tennyson as he “Who felt that faith that sought the Holy Grail” (10). The import of this line can be more fully considered after noting Rawnsley’s use of In Memoriam throughout, but even at this juncture it is clear the Arthurian golden age created by Tennyson through his Idylls is another iteration of the way Tennyson, as the penultimate line of the sonnet declares, “sang two generations back to Christ” (13). Tennyson brought back the Arthurian days by reinstating the quest for the Holy Grail, and that quest is closely linked to Tennyson’s “One memorial utterance for all time” (“The Laureate Dead,” 14).

In “The Laureate Dead,” one line before he speaks of Tennyson bringing back the old Arthurian days, Rawnsley lauds the laureate for leading “us on by love’s undying ways” (6). The term “love’s undying ways” is reminiscent of the famous opening line of the “Prologue” to In Memoriam: “Strong Son of God, immortal Love” (Prologue.1). This connection is borne out by the way that learning to walk in the way of Love is a driving theme throughout Tennyson’s lengthy elegy. An even stronger allusion to a core motif of In Memoriam can be seen in “Christmas Without the Laureate.” There Rawnsley laments:

Yet ah, our voice has failed! The old Church bells

Give back an echo of the songs he sung,

But sadness sounds in every silver tongue

That sends the Christmas message up the fells. (5-8)

Here, Rawnsley uses the church bells of Christmas to express his own, and perhaps the nation’s, feelings of grief at the death of Tennyson, just as Tennyson in two of the best-known cantos (XXVIII, CIV) of his great memorial poem returns to the ringing of the church bells on Christmas Eve to trace the evolution of his grief for Hallam and his search for faith over time. Having established this strong link to In Memoriam, Rawnsley begins to catalogue Tennyson’s greatness, including in that list a couple more allusions to that poem. In the twelfth line, he declares that Tennyson “smote the beast in man with iron rod” (12). This idea of defeating a bestial specter within man is also heard in “I Have Opened the Book” when Rawnsley describes “self” as “to the brutes akin” (7). The seeming suggestion of science that man is but another beast enmeshed in the bloody struggle of nature is a prominent theme in In Memoriam, culminating in Tennyson’s victorious declaration in Canto CXVIII: “Move upward, working out the beast,/ And let the ape and tiger die” (CXVIII.27-28). All of these allusions do more than simply pay homage to Tennyson’s poetry. In each line that alludes to In Memoriam, Rawnsley is elaborating on the details of Tennyson’s spiritual and religious guidance, thus indicating that In Memoriam played, for Rawnsley, a critical role in Tennyson’s mission.

Thus, when Rawnsley states that Tennyson “felt that faith which sought the Holy Grail,” he is bringing together Tennyson’s “one memorial utterance” and “great epic,” indicating that they are united in Tennyson’s single project of singing the nation back to Christ (10). The phrase “felt that faith” echoes Canto CXXIV where Tennyson describes how his heart, refusing to surrender to doubt and disbelief, declares, “‘I have felt’” (CXXIV.16). The syntax of that line also echoes Canto XCVI where Tennyson commends Hallam for his persistence in crafting his faith in the face of doubt, stating, “he beat his music out” (XCVI.10). Tennyson maintains focus on Hallam in that line and those following by beating out his own music through repeating “he” as he details Hallam’s creation of faith through doubt. In the same way, Rawnsley begins lines ten through twelve of “Christmas Without the Laureate” with “Who,” referring to Tennyson. These lines commemorate Tennyson for forging faith through doubt, in much the same way that Tennyson commemorated Hallam; and they go further by indicating that Tennyson not only worked out his own faith but, through his poetry, guided the nation in doing so collectively. This kind of faith then, the tenacious faith that persists through doubt, in short the kind of faith evoked by Tennyson throughout In Memoriam, is also the kind of faith which seeks the Holy Grail. This image, drawing on what Rawnsley suggests are Tennyson’s two greatest poems, indicates that Tennyson’s spiritual vision that united the English people can best be conceived of as a sort of quest. Rawnsley conceives the Tennysonian spiritual center as not a body of beliefs but a common goal, a shared search for belief more than the belief itself.

Little is known at this point about the public reception of these five sonnets, but, based on the sonnets themselves, it seems that Rawnsley felt confident his perspective on Tennyson’s vital role in the spiritual identity of the nation was not merely his own. Rawnsley does not write to prove the importance of Tennyson in Victorian religious understanding but merely assumes that importance and allows it to form the heart of his elegies. Several scholars have noted the widespread popular religious interpretation of Tennyson’s poetry in Victorian England[1], and as such, it is likely that at least a sizable portion of the English Victorian audience who Rawnsley expected to grieve with him through his elegiac sonnets would have held a similar understanding of Tennyson’s function in their society. Thus, Rawnsley’s sonnets illuminate an important way that Tennyson’s life and death was imagined by his contemporaries.

There are still many aspects of the way Rawnsley conceives of Tennyson’s lifework and passing in these poems to be considered. Particularly interesting is the way that Rawnsley seems to vacillate between suggesting that Tennyson’s gift of spiritual identity will wane with Tennyson himself and hoping that Tennyson’s legacy might endure beyond the laureate’s death. One interesting way to explore this question could be by considering the revisions which occurred between Rawnsley’s sonnets as published in Valete and as they are recorded here. In addition, my above analysis might be profitably substantiated, refined, or rebutted by comparison of Rawnsley’s elegiac sonnets with other contemporary elegiac responses to Tennyson’s death. These lines of inquiry and likely many others could yield valuable insight into the ways that Tennyson was remembered in relation to the Victorian period which he did so much to shape.

Works Cited

Blair, Kirstie. Form and Faith in Victorian Poetry. 1st ed., Oxford University Press, 2012.

King, Joshua. Imagined Spiritual Communities in Britain’s Age of Print. Ohio State University Press, 2015.

Laporte, Charles. Victorian Poets and the Changing Bible. University of Virginia Press, 2011.

Rawnsley, Hardwicke Drummond, et. al. Memories of the Tennysons. 2nd ed., J. Maclehose and Sons, 1912.

Tennyson, Alfred Lord. “In Memoriam A.H.H.” Tennyson: A Selected Edition, edited by Christopher Ricks, Routledge, 2014, pp. 341-484.

[1] E.g. Kirstie Blair, Charles LaPorte, and Joshua King.