Bound copy of 1843 Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine featuring the first version of EBB’s “The Cry of the Children.”

Browning, Elizabeth Barrett. “The Cry of the Children.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 44 (August 1843). CCCXXXIV. Edinburgh: William Blackwood; London: T. Cadell and W. Davis: pp. 260-262. ABLibrary Periodicals

Rare Item Analysis: Textual Revisions and Constructed Narratives in Elizabeth Barrett’s “The Cry of the Children”

by Meagan Anthony

It is not surprising that the Armstrong Browning Library, known for its expansive collection of Browning manuscripts, would possess a first printing of Elizabeth Barrett’s (then unmarried) poem “The Cry of the Children.” This artifact is a bound collection of Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, containing several month’s publications from 1843. The section of interest to this discussion is from August 1843. This text is available for study through the Armstrong Browning Library’s rare periodicals collection. Unlike many rare items at the Armstrong Browning Library, this Blackwood’s collection was not owned by the Brownings, nor did it belong to a friend or another noteworthy author. Those most related to this item, other than Barrett (1806-1861), are Richard Hengist Horne (1802-1884) and the Blackwood family. The value of this text is in its production of the first published version of “The Cry of the Children” and the insight that comparison of this version with later ones can lend into important changes that Elizabeth Barrett made to the poem’s text and placement alongside other works.

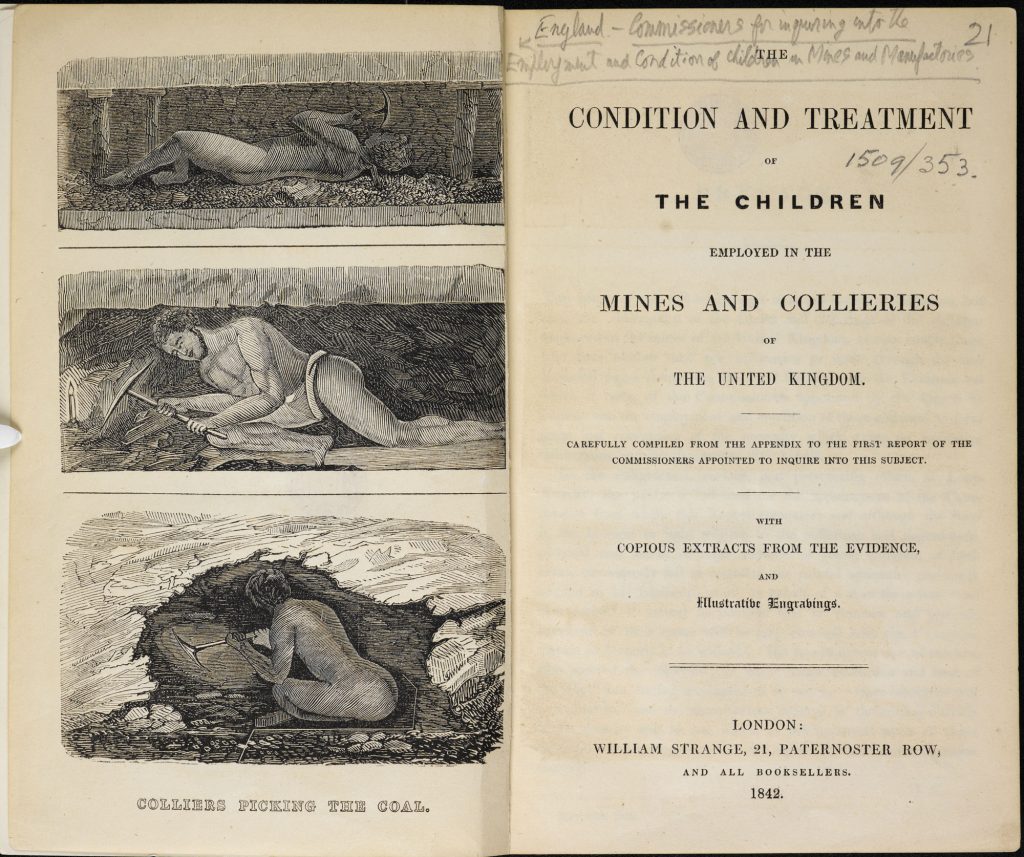

Barrett was inspired to write “The Cry of the Children” by her communication with Richard Hengist Horne (R. H. Horne). Horne worked as an interviewer for the “Children’s Employment Commission on the conditions of work in collieries and mines.” Published in 1842, a year before Barrett would publish “The Cry of the Children,” the commission’s report uncovered a startling amount of violence, unsafe, and unsanitary working conditions. Men, women, and children were becoming ill and disfigured from stooping, crawling, and carrying massive amounts of weight. One of the issues the report uncovered, which was of particular concern for Barrett, was the children’s almost complete lack of religious knowledge (Donaldson 431). In a letter dated August 7th, 1843, Barrett tells Horne that her poem “owes its utterance to your exciting causations,” thus directly linking “The Cry of the Children” to the commission’s report (1349; this letter exists in an online edition of The Brownings’ Correspondence available through the ABL).

Another interesting aspect of this version of “The Cry of the Children” is the speed of the publication. For a poet known for her deep involvement in the editing and production of her work, Barrett composed and published this poem unusually. Barrett describes her experience of the process to Hugh Stuart Boyd: “The first stanza came into my head in a hurricane, & I was obliged to make the other stanzas like it” (Stone 148). Well aware of the hurried nature of the publication, on August 1st, 1843, Barrett wrote to her brother George Goodin Moulton-Barrett: “From the advertisement I perceive the ‘Cry of the children’ in the coming Blackwood, & am quite frightened to look at the print of it, through the excess of my anticipation of Printers’ faults- So stupid as it was in me, not to beg from the first moment, for a proofsheet! So hurriedly as the M.S. copy was transcribed! so rapidly looked over!” (1343; this letter and the previous letter to Boyd are also available via The Browning Correspondence database). Because of this “hurried” production, it is no wonder that Barrett produced, at minimum, four different versions of “The Cry of the Children,” printed in various editions of her books of poetry.

In 1844, a year after its initial appearance in Blackwood’s, “The Cry of the Children” was featured in her book Poems (published in America under the title A Drama of Exile, and other Poems). The revisions in the 1844 version are seemingly minor – a word here or there, with no great structural changes – yet these relatively minor changes indicate what Barrett sees as most important in her poem: bridging the gap between the child subjects and the reader and establishing empathy.

One of the ways Barrett accomplishes these goals is to concentrate on the age of the children. In the first stanza, line 9, the 1843 version uses “the young children,” but in the 1844 version Barrett places extra emphasis by adding “young” once over: “the young, young children” (Donaldson 439). The repetition in this line breaks up the parallel imagery from the previous lines: “young lambs,” “young birds,” “young fawns,” “young flowers.” This alteration of parallel sentence structure causes the reader to falter for a moment, which draws attention to the repeated word “young.” Unlike these youthful images of nature, it soon becomes apparent that the “young, young children” are psychologically and physically aged from their toil.

Barrett continues to close the gap between the reader and the children. In line 22, Barrett alters the “ye,” in “Do ye ask them why they stand,” for “you” (439). This accomplishes two things: first, the “Brothers” she addresses are presented with the more personal pronoun “you” to forge a relationship with the narrator, and therefore the children. However, this technique also works to point a finger at the reader as a potential enabler of these children’s suffering, just as the poem accuses the brothers. The line then reads: “Do you ask them why they stand / Weeping before the bosoms of their mothers, / In our happy Fatherland?”

Throughout the rest of the poem Barrett replaces articles with more personal pronouns. In line 39 “the grave” becomes “her grave,” and in line 62 “the weeds” becomes “our weeds” (Donaldson 440). With these changes, the communal voice of the children becomes more pronounced and reminds the reader of the humanity linked to the voices and the multiplicity of the voices. Adding to that emphasis of the number of children, in line 70 “face” becomes “faces.”

Another core of Barrett’s revisions surround the children’s relationship with religion. One of the aspects that came to light in the commission’s report was their near absolute lack of knowledge about the Bible and other religious aspects (Donaldson 431). A primary concern for Barrett was that this lack of knowledge, alongside absence of signs of human or divine mercy, would create a generation of non-believers. This consideration is echoed in line 131, “Do not mock us; we are atheists in our grieving,” which is changed to “grief has made us unbelieving” in 1844 and after. This alteration accentuates the negativity behind this idea of lacking belief. “Atheist” is a more clinical and less clandestine image, while “unbelieving” captures the active negation of belief.

In the 1844 revision, Barrett links the “Brothers” to the clergy and others in positions of relative affluence who offer moral spiritual platitudes in response to the children’s suffering, merging the poem’s accusation of the “Brothers” to the fault of the church and traditional authority. Lines 133-136 present the climax of the poem’s indictment of the brothers:

Do you hear the children weeping and disproving,

O my brothers, what ye teach?

For God’s possible is taught by His world’s loving,

And the children doubt of each. (1843 version)

Barrett charges the brothers with being the cause of the children’s trending towards “unbelieving,” because they have failed to exhibit God’s love in their actions towards these child workers. Yet, in this version, the brothers’ identity is up for interpretation – they could be London citizens who standby and do nothing, factory owners who take advantage of the poverty of the children’s families, etc. However, in the 1844 version, Barrett withdraws the ambiguity of the brothers, and it becomes apparent that the brothers are likely members of the church. By simply changing the word “teach” into “preach,” Barrett perhaps questions those in positions of power, such as clergymen, who could arguably have done more to speak for the suffering children. By turning a deaf ear to the “weeping” children, by being selective in who receives the church’s love, Barrett calls church leaders, members of government, and the social elite to task for creating children who “doubt” God’s love, because His voices on earth have neglected their work with those who suffer.

The other discussion surrounding the first publication of “The Cry of the Children” involves how different publishing strategies, of Blackwood’s and Barrett, potentially created varied reader responses to the poem. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine was launched in 1817. The publication “featured sharp attacks on local and national literary figures, as well as an unusual blend of anonymously authored literature, politics, fiction and poetry” (Finkelstein). The editors of the magazine through the early twentieth century were the members of the Blackwood family, beginning with William Blackwood I. Editors William Blackwood I (1817-1834), John Blackwood (1845-1879), and William Blackwood III (1879-1912) were known for their conservative Tory tendencies. However, the year Barrett published “The Cry of the Children” little is known about the editors, Robert and Alexander Blackwood. There is no record of any correspondence between Barrett and the magazine prior to this publication.

Because the magazine was known for its conservative Tory bias and a strong affiliation with agrarian landowners, it may seem like a strange publication choice for Barrett, who is known to have been more socially liberal with strong Whig affiliations. Yet these strange bedfellows shared a common enemy: London industrialists. Barrett often wrote about her concern for the children suffering in the factories and industrial mines, and the factories were natural rivals for the agricultural-focused Blackwood’s. The magazine uses Barrett’s appalling image of industrial factories to strengthen its pro-agrarian agenda, and simultaneously, Barrett creates an audience for herself out of readers who would most likely never seek out poetry from a socially progressive poet.

While Barrett’s publication in Blackwood’s gives an interesting insight into the first version of “The Cry of the Children,” how the magazine frames the poem adds another layer of significance to how the reader would have experienced the poem. In the August 1843 edition of Blackwood’s, a satirical poem, written by an anonymous poet, called “Jolly Father Joe” directly precedes Barrett’s “The Cry of the Children.” The poem is about a drunken Catholic priest who wanders about in his drunken state and happens upon the Virgin Mary. He seems to take her advice to heart that he should be a better man and act appropriately, and the poem ends with the narrator speaking directly to the reader about the necessity of ladies to correct the immoral male:

May it prevail this moral to impress

On good men all, who’re apt to fall at times into excess,

To seek the ladies’ company when sins or wine entice,

And strive not only for their smiles, but follow their advice. (“Jolly” 259)

This nod toward female wisdom regarding moral issues prepares the reader for Barrett’s poem pleading for a moral solution to suffering child workers. In this light, “Jolly Father Joe” is a perfect pairing for Barrett’s message; however, “Jolly Father Joe” is highly satirical in its account of the Catholic protagonist. Therefore, the decisions he makes – listening to the woman could be considered one of those decisions – are depicted as farcical. “Jolly Father Joe” is situated after a commercial policy argument, which foreshadows Barrett’s discussion of poor workers. Linda Hughes is one of the only scholars who has commented on the placement of “The Cry of the Children” in Blackwood’s:

Could the reader who glanced only at the first page of “Commercial Policy—Europe,” an unsigned middle, forget entirely its mention of workhouse residents or masses in want of bread by the time he or she got to Elizabeth B. Barret’s [sic] poem “The Cry of the Children” a few pages on? If the reader actually read “Commercial Policy—Europe,” a serious article urging at least residual protectionism, could that reader manage to stop the eyes at the end of the article mid-page before glancing at the humorous poem about a drunkard friar (“Jolly Father Joe”) that shares the page and introduces a raucously different tone and voice? Or fail to notice that the anonymous doggerel poem’s concluding line, “And may the writer always have the ladies for his friends,” is succeeded on the next page by the signed poem of a woman? (293)

Readers going from reading this poem to reading “The Cry of the Children” on the same page could transfer the satirical momentum of the priest and his mystical lady to the lady poet and her entreaty for the children, easily hampering the significance and credibility Barrett would have expected.

In 1850, in her second edition of her book Poems, Barrett’s own poetic narrative positioned “The Cry of the Children” directly after “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point.” The reason Barrett gave for this positioning was “to appear impartial as to national grievances” (Stone 149). She situates the graphic depiction of the experience of the American slave ahead of “The Cry of the Children” to diminish the potential backlash for so heavily critiquing her own nation. This construction could display an awareness of the poem’s original, conservative, audience from Blackwood’s and be an attempt to fuse the conservative and liberal audiences. However, both these poems put on full display her social liberalism and abolitionist ideals. This placement also reinforces for the reader Barrett’s international concern for human and children’s suffering. She presents a worldwide need for a moral renaissance expanding from her own shores.

Critics of her poem first appeared after its first publication in book form, in her 1844 edition of Poems. Reviews tended to agree on the positive and negative aspects of the poem. While they agreed that the meter was nigh impossible to follow (something that she admits in some of her letters after publication), they mainly praised her passion and ability to render into a poem such an impactful and significant issue. Her use of feeling is most noted as a laudable skill. In letters to Hugh Stuart Boyd, Barrett comments on her poem’s need for “versification” (1374); however, her letters do not indicate her opinion on the critics’ emphasis on her depth of feeling rather than other poetic nuances. Her ability to express emotion through her poetry is indicative of the sort of review given to a female poet, the kind of review Barrett discusses in Aurora Leigh: “You never can be satisfied with praise / Which men give women when they judge a book / Not as mere work but as mere women’s work” (Browning 2.232-234). This commentary about women authors in Aurora Leigh, published thirteen years after the first version of “The Cry of the Children,” could have been influenced by the criticism she received regarding the womanly feeling in “The Cry of the Children.”

This rare book, containing Elizabeth Barrett’s first publication of “The Cry of the Children,” is a significant part of the poet’s history. Many more trails of scholarly research could be examined apart from those I have discussed. While I have mentioned changes in the poem between its first publication and second publication, I have by no means exhausted all the specific line edits, and much more could be said to illuminate new meaning. And though I discussed how the placement of the poem in Blackwood’s and the 1850 Poems shaped the reader’s experience of “The Cry of the Children,” more could be said about the works following the poem in each publication, as well as Barrett’s placement of “The Cry of the Children” in her other books of poetry. The Armstrong Browning Library has many rare items relating to this poem along with critical commentary. As a resource for future study, The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, edited by Sandra Donaldson, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Selected Poems, edited by Marjorie Stone and Beverly Taylor, both provide significant background information and source material. They also offer considerable footnotes regarding secondary sources and Barrett’s edits of the poem.

Works Cited

Barrett Browning, Elizabeth. Aurora Leigh. Edited by Margaret Reynolds, W.W. Norton & Co., 1996.

Donaldson, Sandra. “The Cry of the Children.” The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, vol. 2, Pickering & Chatto, 2010, pp. 431-435.

Finkelstein, David. “Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine.” Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Journalism, 2017, C19: The Nineteenth Century Index, http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.baylor.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:c19index-us&rft_dat=xri:c19index:DNCJ:146. Accessed 2 March 2017.

Hughes, Linda K. “Media by Bakhtin/Bakhtin Mediated.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 44, no. 3, 2011, pp. 293-297. www.jstor.org/stable/23079112.

“Jolly Father Joe.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 44 (August 1843). CCCXXXIV. Edinburgh: William Blackwood; London: T. Cadell and W. Davis: p. 259. ABLibrary Periodicals.

Stone, Marjorie and Beverly Taylor, editors. “The Cry of the Children.” Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Selected Poems. Broadview, 2009, pp. 148-156.