John Keble. The Christian Year: Thoughts in Verse for the Sundays and holydays throughout the Year. 2nd ed. Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter, for J. Parker and C. and J. Rivington, 1827 (ABL 19thC Collection PR4839.K15 C4 1827)

Charlotte M. Yonge. Musings over the “Christian Year” and “Lyra Innocentium.” 2nd ed. Oxford: James Parker and Co, 1872 (ABL 19thC Collection PR4839.K15 Z9 1872)

Rare Items Analysis: Private and Public Interpretations of John Keble’s The Christian Year

by Christopher Yang

John Keble’s best-selling volume of poetry, The Christian Year (1827), although relatively obscure to modern readers, was arguably as influential as Tennyson’s In Memoriam or Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh; approximately half a million copies were sold, 158 editions were published before 1873, and “nearly every literate Victorian household would have had [a copy]” (King 1). We are fortunate to have a second edition copy of Keble’s The Christian Year in the 19th century collection of the Armstrong Browning Library that was owned by the Coleridge family and contains annotations made in part by Derwent Coleridge. Charlotte Yonge’s commentary on Keble’s volume of poetry, Musings over the “Christian Year” and “Lyra Innocentium” (1872), is also held in the Armstrong Browning Library in the 19th century collection. Such rare items give modern scholars insight into how Keble’s contemporaries would have analyzed and interpreted his poetry.

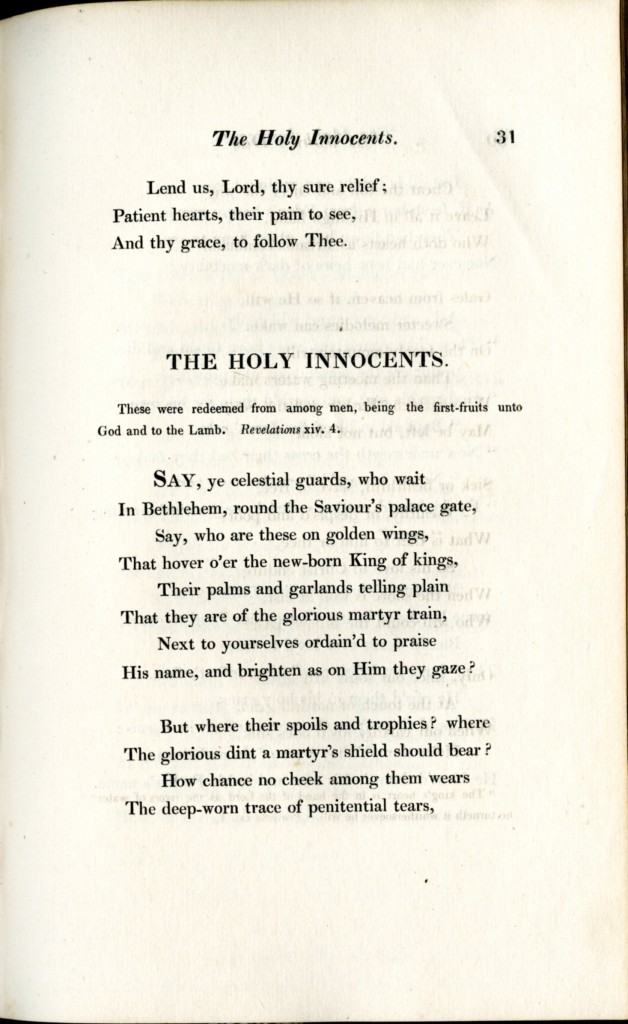

Although scarce, annotations in the Coleridge family’s copy of The Christian Year offer interesting remarks on Keble’s poem Holy Innocents. The first stanzas of the poem depict an onlooker witnessing the resurrected infants who were slaughtered by Herod and the poet’s reaction to their joy. The poet then meditates on Jesus’ blessing of the children, his blessing not limited to either the children he held at the moment or those slaughtered for his sake, but for all Christian children in the generations to come. Emphasizing their protection under God, the poet reflects:

And next to these, thy gracious word

Was as a pledge of benediction, stor’d

For Christian mothers, while they moan

Their treasur’d hopes, just born, baptiz’d, and gone

Oh joy for Rachel’s broken heart!

She and her babes shall meet no more to part;

So dear to Christ her pious haste

To trust them in his arms, for ever safe embrac’d. (Keble ll. 41-48)

In the margins of the page, an unidentified annotator writes “But the Holy Innocents were they baptized? yes [sic] with the baptism of blood! and [sic] will not the blood of Christ – will not the free love of God baptize all infants when he has taken them to himself thus early – Christian or Pagan?” Here, the annotator challenges the notion that only Christian infants are born into Christ, suggesting instead that Christ’s sacrifice was intended for all his people, not only his followers, since all infants were baptized by the “blood” and “free love” of God. However despite giving this implication, the annotator does not seem able to accept this idea entirely as denoted by the question mark. An alternative interpretation of the remarks could be an expression of the annotator’s doubts of whether Christ actually died for all people or if this idea is Christian or pagan. Another annotation likely by Derwent Coleridge catches Keble’s reference to one of William Wordsworth’s poems, Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood (1807), by writing “Wordsworth” in the margin next to the earlier line “Ocean’s boundless roar” (ll. 36). In Ode, Wordsworth writes “Our souls have sight of that immortal sea” (ll. 168), suggesting that as children we have a vague recollection of preternatural origins; Keble proposes that these origins are a child’s memory of coming from God. As the third child of the preeminent poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge—who worked closely with Wordsworth—Derwent

Coleridge would be aware of explicit references to him.

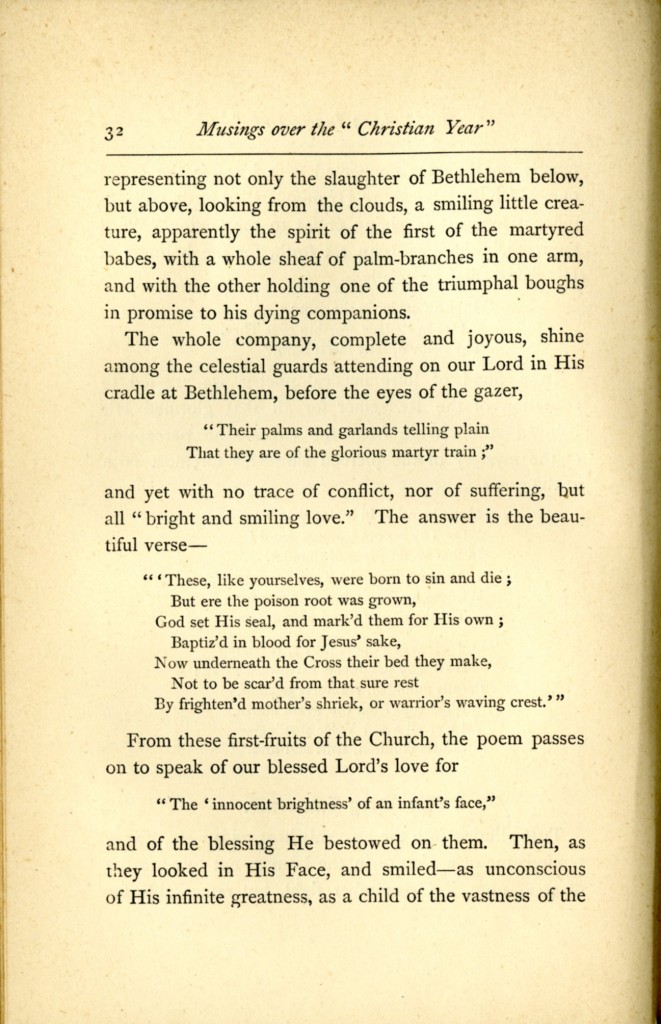

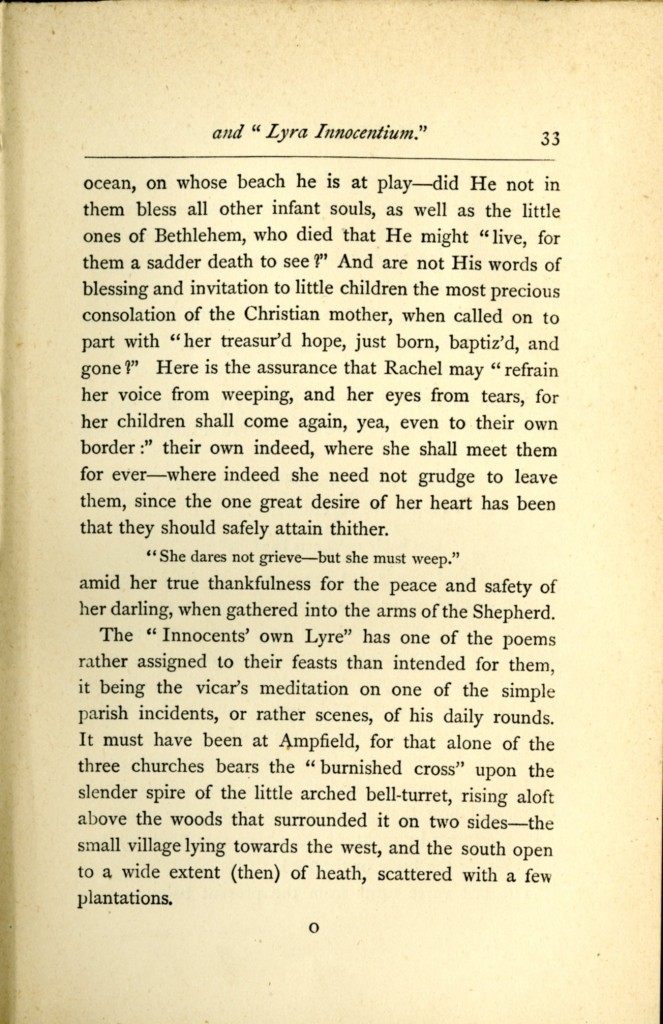

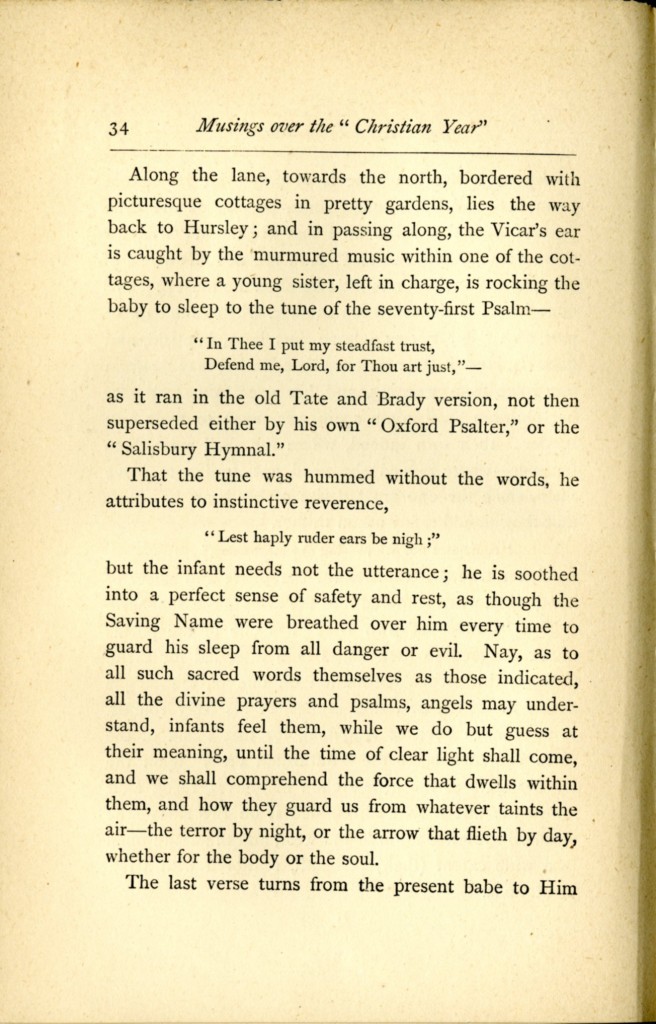

Charlotte Yonge, a student of Keble, also remarks on this passage, among others, in her published commentary, Musings. After offering some brief comments that the poem reminds her of a picture in the Louvre, she continues to say, “and are not his [Jesus] words of blessing and invitation to the little children the most precious consolation of the Christian mother” (Yonge 33). She again emphasizes that these children, all children in Christ, are protected under his sacrifice and cannot be harmed, stating “for even should the little life be cut short . . . what doth the infant but glorify his Lord by his death” (33). Although Yonge could not have read the annotations on Keble’s poem in the Coleridge family’s copy, she addresses a similar issue, affirming the unidentified annotator’s implicit answer; according to her interpretation, all the holy innocents who died, although without physical baptism, still honor God with their deaths and are assured a place in his kingdom. In the preface of her book, Yonge recounts her interactions with Keble during her time under his tutorship and provides several letters of correspondence they sent each other. Having been sent to Keble’s vicarage in her early adolescent years and kept in continual correspondence with him, Yonge is able to offer unique insights into his poetry, motivations, and inspirations, which would be overlooked by all except his close friends.

Thus, because of their proximity to John Keble’s time, the comments made in the Coleridge family’s copy and by Charlotte Yonge remain pertinent for modern students and scholars of Keble’s The Christian Year. The annotations in the Coleridge copy offer a firsthand, private interpretation of Keble’s poetry, while Yonge’s commentary can highlight personal experiences or inspirations for each poem of The Christian Year, giving us insight into how Yonge interpreted these poems for the broader public and how Keble’s readers would have understood these poems in light of her interpretations. Future research could focus on the correspondence between Keble and Yonge and illuminate any potential inspirations or revisions to The Christian Year, developing new ways to understand his best-selling volume of poetry.

Work Cited

King, Joshua. “John Keble’s The Christian Year: Private Reading And Imagined National Religious Community.” Victorian Literature And Culture 40.2 (2012): 397-420. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 7 May 2016.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|