Baron Alfred Tennyson Manuscript:

“To the Queen” Draft [N.D.]

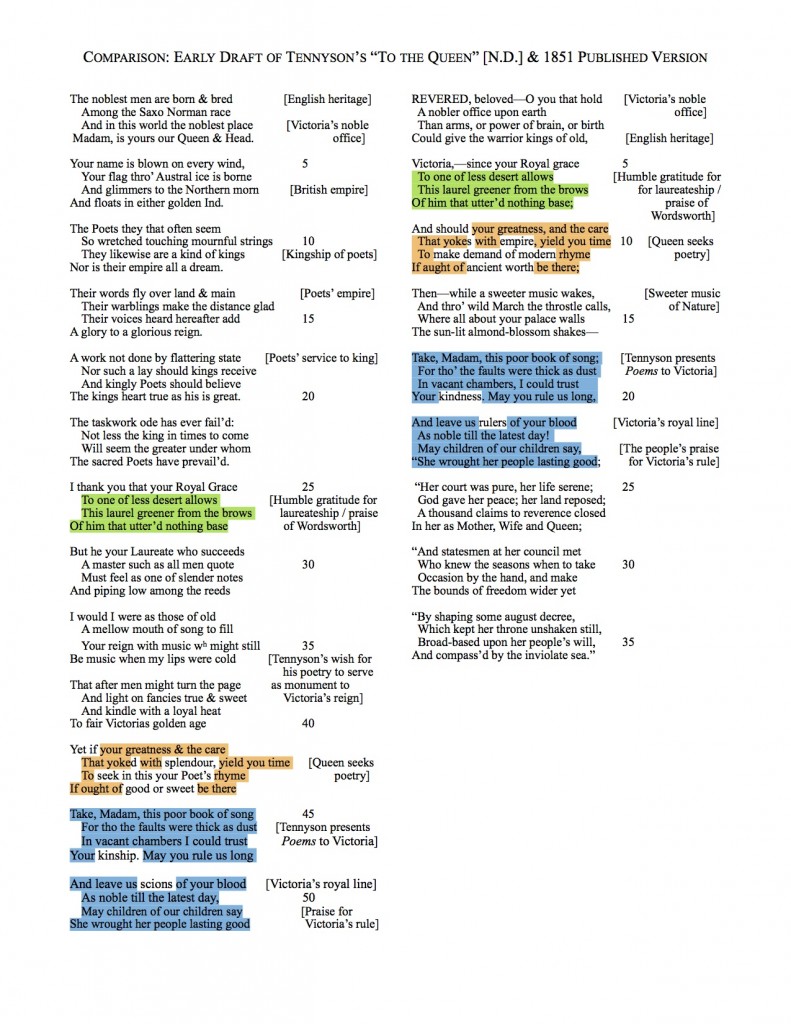

Rare Item Analysis: Comparison of an Early Draft of Tennyson’s “To the Queen” [N.D.] and the 1851 Published Version

By Loren Warf

About the Manuscript:

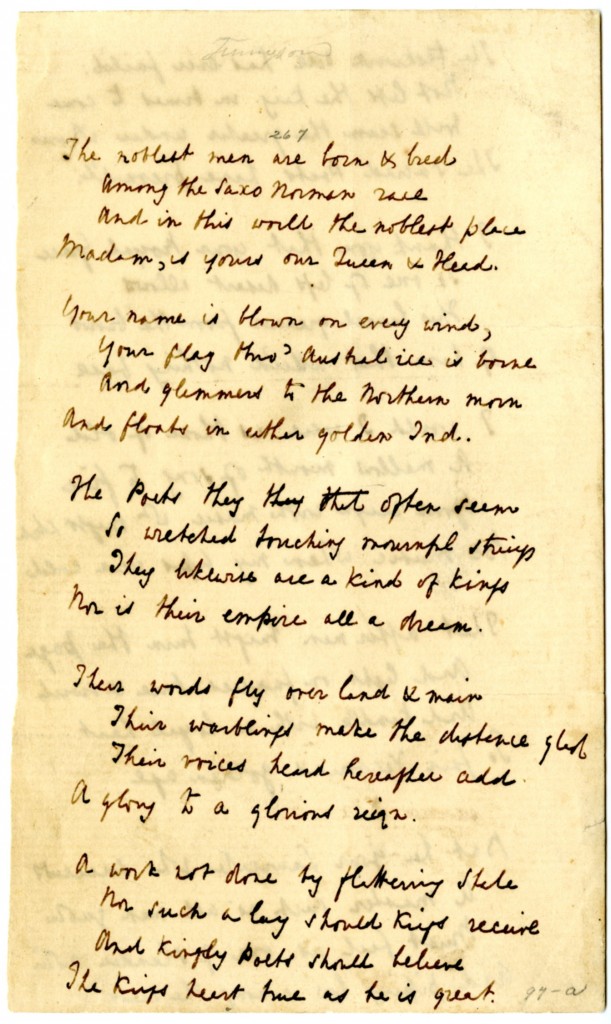

Among the holdings of the Armstrong Browning Library (ABL) at Baylor University is a manuscript of an undated early draft of Alfred Tennyson’s “To the Queen.” “To the Queen” was published in 1851 as the dedication to Poems, Tennyson’s first published work as poet laureate. Tennyson substantially altered the poem between the ABL draft and the published version. These alterations give us insight into Tennyson’s developing conception of his role as poet laureate. The ABL manuscript is a fair copy of an early draft, written in Tennyson’s hand on three separate 12mo pages. The provenance of this item is uncertain. It is possible that the manuscript was once housed at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia. While the ABL manuscript seems to be consistent with the Drexel manuscript in content, the ABL’s curators are not certain it is the same document. The Drexel manuscript was sold in 1944. The ABL acquired its manuscript in 1997.

This manuscript is located in the ABL’s Victorian Manuscripts Collection. While all manuscripts of works by Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning housed at the ABL are listed with call numbers in The Brownings: A Research Guide, manuscripts by other Victorian authors are not given call numbers. To access this early draft of “To the Queen,” contact the ABL’s Curator of Manuscripts.

Analysis:

Tennyson significantly altered “To the Queen” from the ABL draft to the published version. The ABL draft is comprised of thirteen stanzas, while the published version contains only nine. Of the thirteen stanzas from the early draft, only four remain in the published version. Most of the deleted stanzas focus on the role of the poet and poetry. While these subjects are still central to the published version, there Tennyson gives more attention to Victoria and her rule.

Like the first two stanzas of the ABL draft, the version of “To the Queen” which appears in Poems begins by proclaiming the nobility of Victoria’s royal office. However, the later poem places the emphasis on Victoria herself, where the early draft focuses on the British heritage and empire. The opening stanzas of the ABL draft are as follows:

The noblest men are born & bred

Among the Saxo Norman race

And in this world the noblest place

Madam, is yours our Queen & Head.

Your name is blown on every wind,

Your flag thro’ Austral ice is borne

And glimmers to the Northern morn

And floats in either golden Ind. (ll. 1-8)

The poem opens with a celebration of the British people as “[t]he noblest men” (1). Victoria’s is, therefore, the “noblest place” precisely because it is the highest place among the British people. Likewise, in the second stanza, the queen’s name and flag are the subjects, but the emphasis is on the expansiveness of the British empire. In the final draft, however, the focus shifts toward Victoria herself:

REVERED, beloved—O you that hold

A nobler office upon earth

Than arms, or power of brain, or birth

Could give the warrior kings of old, (ll 1-4)

Here, Tennyson praises both the office of the queen and the queen herself. Though he does not mention her by name until the second stanza, Victoria is the one “REVERED” and “beloved” (1). There is also a sense of progress here that was not present in the earlier draft. Rather than praising the Saxo-Norman heritage of Britain, Tennyson places Victoria above the “warrior kings of old” (4). Her office as the British queen is not only more noble than the royal offices of other nations, it is more noble than those of previous British rulers. This distinction between Victoria and the “warrior kings” is important given Tennyson’s focus on her peaceful reign later in the poem.

In the next four stanzas of the ABL draft, Tennyson shifts his attention from the office of the queen to the office of the poet:

The Poets they that often seem

So wretched touching mournful strings

They likewise are a kind of kings

Nor is their empire all a dream.

Their words fly over land & main

Their warblings make the distance glad

Their voices heard hereafter add

A glory to a glorious reign.

A work not done by flattering state

Nor such a lay should kings receive

And kingly Poets should believe

The kings heart true as his is great.

The taskwork ode has ever fail’d:

Not less the king in times to come

Will seem the greater under whom

The sacred Poets have prevail’d. (ll. 9-24)

Like kings, Tennyson argues, poets preside over empires. Their words, which spread beyond national boundaries, have a real, substantive power. In these stanzas, Tennyson contemplates the use of this power in his role as poet laureate. A poet laureate, according to Tennyson, has the ability to “add / A glory to a glorious reign,” but in order to do so, he must be willing to speak the truth and avoid flattery (ll. 15-16). If the noble poet will speak what is good and true, king and country will seem even greater. Although Tennyson mentions kings in these stanzas, his focus is primarily on the poet and the power of poetry. Kings might be great, but Tennyson stresses that their perception is made even greater under the ‘rule’ of great poets. While the first two stanzas of the ABL draft focus on Victoria’s empire, the poet’s empire begins to eclipse Victoria’s in the next four. Ultimately, the lasting empire is the poet’s, and Victoria’s is subsumed in it. Tennyson, probably wisely, leaves these stanzas out of the published version, leaving Victoria’s as the sole empire immortalized in the verse of “To the Queen.”

The seventh stanza of the ABL draft—which thanks Victoria for the laureateship and acknowledges the greatness of the previous poet laureate, William Wordsworth—remains largely intact in the published version, though it becomes the second stanza rather than the seventh. The most significant change is Tennyson’s decision to address Victoria by name. This change, along with the removal of the stanzas focusing on the poet’s empire, makes the poem more fitting of the title “To the Queen.”

At this point, in the ABL draft, Tennyson includes three more stanzas on poets and poetry which disappear from the final version. Stanza eight expresses his own humility as he accepts the position Wordsworth once held:

But he your Laureate who succeeds

A master such as all men quote

Must feel as one of slender notes

And piping low among the reeds (ll. 29-32)

In his modesty, however, Tennyson takes yet another opportunity to proclaim the power of poetry:

I would I were as those of old

A mellow mouth of song to fill

Your reign with music wh might still

Be music when my lips were cold

That after men might turn the page

And light on fancies true & sweet

And kindle with a loyal heat

To fair Victorias golden age (ll. 33-40)

Here, Tennyson expresses his desire to rank among the old, great poets whose “music” lingers on long after they have died. His desire to be great arises from his devotion to the queen and his eagerness to bring greater glory to her memory. His use of the subjunctive here expresses his desire, but it also turns these stanzas into something of a prophecy. The word “would” here seems to indicate something stronger than a mere wish. Instead, Tennyson seems to be willing himself into the category of the greats, leaving little question by the end of these stanzas that his poetry will succeed in immortalizing Victoria’s reign.

Tennyson kept the final three stanzas of the ABL draft in the final version of “To the Queen,” but he moved them toward the center of the poem. In these stanzas, he presents his book Poems to Queen Victoria to read when the responsibilities of her office “yield [her] time” (l. 42). Tennyson expresses his belief that Victoria will be a charitable reader who will appreciate his works despite their faults. He then closes the poem with a blessing for Victoria’s reign:

. . . May you rule us long

And leave us scions of your blood

As noble till the latest day,

May children of our children say

She wrought her people lasting good (ll. 48-52)

In this final blessing, Tennyson expresses his hope that Victoria will be a praiseworthy queen and produce heirs. The final word, “good,” gives the sense at the end of the poem that both Victoria and Tennyson will succeed. Victoria will reign well, and Tennyson will ennoble her reign with his verse.

Although Tennyson removed the stanzas pertaining to poets and the purpose of poetry which were so prominent in the ABL draft, readers can still locate many of these themes in the final version of the poem. Instead of explaining his theories about poetry and the role of the poet laureate, Tennyson enacts these theories in published version of “To the Queen.” While he talks about singing Victoria’s praise in the earlier draft, in the later one, he actually sings her praise. He opens, “REVERED, beloved,” and he even alters his punctuation, inserting dashes which break up the regular iambic tetrameter and force readers to linger over these positive adjectives. In the ABL draft, he does not mention Victoria by name until the tenth stanza, but in the published version, her name appears at the opening of the second stanza. Again, he inserts a dash, forcing readers to emphasize the name of the queen. The earlier draft declares that a poet laureate will bring glory to the queen; the final draft brings glory to queen.

Tennyson closes the ABL draft with the hope that the “children of our children” will extol Victoria’s reign. In the published version, Tennyson gives us three new stanzas which tell us what these children will say:

“Her court was pure, her life serene;

God gave her peace; her land reposed;

A thousand claims to reverence closed

In her as Mother, Wife and Queen;

“And statesmen at her council met

Who knew the seasons when to take

Occasion by the hand, and make

The bounds of freedom wider yet

“By shaping some august decree,

Which kept her throne unshaken still,

Broad-based upon her people’s will,

And compass’d by the inviolate sea.”

This is yet another instance of Tennyson’s enactment of his theories from the earlier draft. By adding these stanzas, Tennyson is able to determine exactly what part of Victoria’s reign is praised. Here, he chooses to focus on her empire, her peaceful rule, and her womanly virtue. He sets Victoria above the “warrior kings of old” (1). His claim seems to be that the one who can maintain a peaceful control over an expansive empire is more noble than those who increase the empire through bloodshed. Of course, the idea that Victoria’s rule was entirely “pure” or “serene” is naive. Victoria’s rule did, after all, see its share of violence bloodshed. However, such facts do not fit with Tennyson’s vision of Victoria as a woman and a queen. Tennyson grants the political power of these last three stanzas to Victoria’s statesmen. They rule “at her council,” but they are the ones expanding “[t]he bounds of freedom” and “shaping . . . decree[s]” which keep “her throne unshaken still” (ll. 32-34). Victoria’s virtue lies in her femininity, in her fulfillment of her duties as “Mother, Wife and Queen,” seemingly in that order (l. 28). Victoria becomes the ideal mother, not only of her children but of her country, and Tennyson carefully crafts this image of her.

While it may seem at first glance that Tennyson takes the focus away from the role of the poet in the published version of “To the Queen,” the poet is still very much at the center of the poem. In the final version, Tennyson shapes each image carefully, determining the particular vision of Victoria’s reign that readers will be left with. Upon close examination, it becomes clear that the poet is also physically at the center of the poem. The few stanzas which remain from the earlier draft, all of which relate directly to Tennyson and to his work, are placed at the center of the poem. Therefore, although Tennyson significantly alters “To the Queen,” making its subject more appropriate to its title, he still manages to situate the poet and poetry—his own work in particular—at the heart of the poem.

Archival research can add depth to literary study. As demonstrated above, comparing early drafts of works to final, published products can highlight particular themes or reveal new aspects of a writer’s development. Therefore, items in the ABL’s Victorian Manuscripts Collection could be particularly useful in the literature classroom. In addition, since a study of successive drafts puts a strong emphasis on writing as a process, such items could also be helpful resources for the composition classroom.

Warf To the Queen Comparison Handout