The 1930s were a time of economic despair for most of America. The Great Depression struck at the end of 1929 and left the country financially wrecked and for the most part unemployed. According the The Bureau of Labor Statistics, about one-fourth of the labor force were out of work, an estimated 12,830,000 people (Bernstein, 1976). Neither the state of Texas nor Baylor University were immune to this nationwide hardship.

At Baylor, former Governor Pat Morris Neff was named President in 1932. Neff implemented strict policies for both student activities and financial practices. As a well-known figure in Texas and as President of the university, he often served as the main correspondent with prospective students and their parents. Through these letters, many expressed interest in coming to Baylor and asked for financial assistance. Baylor had the resources to provide scholarships for a small group of students based on merit, parental occupation and choice of study. Neff, however, pushed for mutually beneficial ways to provide access to higher education and often encouraged students to stay at home if they could not afford to attend Baylor.

Despite the harsh economic conditions of the 1930s, Pat Neff and Baylor University worked hard to alleviate financial burdens and widen access by offering scholarships, ministerial assistance, on-campus employment, and accepting unconventional trades as payment methods for tuition. Through these creative financial policies, many were able to study at Baylor without going into debt. Neff’s correspondence with prospective students provides insight into his personal attitude towards higher education and debt. Neff is quick to offer many scholarships to qualified applicants but is often brutally honest about the full cost of Baylor, the likelihood of receiving a job in the Waco community and the stress that both of those issues can place on a student’s academic endeavors.

Scholarships

According to the Baylor Bulletin (1934), there were a variety of scholarships available for both prospective and current students at Baylor. The High School Scholarship was granted to the highest honor graduate of any affiliated Texas high school and could be transferred to the second honor graduate if the original recipient chose not to attend Baylor. Another scholarship that was available was specifically for a graduate of the Masonic Home and School of Fort Worth. A notable recipient of this scholarship was future Baylor president, Abner McCall (McCall, 1933).

In a letter to Neff, one Waco local asked about assistance for her daughter to attend Baylor. Neff told her that McClennan County residents could receive half of their tuition upon acceptance into Baylor, a policy that was not widely publicized but used to assist those who inquired (Back, 1933). Harold Barclay, a young man that came very well recommended as both a student and football player, asked Neff if there were any scholarship opportunities for athletes. Neff congratulated him on his athletic accomplishments and welcomed him to try for the football team, but bluntly told him that no athletic scholarships were awarded (Barclay, 1933).

Ministerial Assistance

As a Baptist institution, Baylor University had a positive reputation among Baptist ministers and missionaries from around the country. According to the Baylor Bulletin (1934), Baylor offered two ministerial scholarships. The first, for ministers’ children under the age of 21, was available to “children of Baptist ministers, actively engaged in the ministry as a life work and in hearty cooperation with the University” (Baylor Bulletin, 1934, p. 53). This scholarship entitled them to half-tuition. The second ministerial scholarship was for students that presented “written certificates of ordination or license by any Baptist church,” and provided full tuition to ministers and their wives (Baylor Bulletin, 1934, p. 53).

Campus Jobs

The most common request from prospective students was for “honorable” work in exchange for tuition. For the most part, Neff responded to letters with affirmation that a position could be counted on, provided they live on campus and could otherwise finance themselves. Students who were employed by the University received some portion of their tuition, depending on both the amount of hours worked, their specified need, and Neff’s personal discretion. Student employees were required to live on campus, with only a few exceptions being made for those with family in Waco or surrounding areas.

According to student employee records, over 1,000 students were employed by the university during the 1939 fall term (Alphabetical List of Student Employees – Fall 1939, 1939). The jobs ranged from stenographer to kitchen aid and students, especially first years, had little say as to their job placement. Many enrolled on Neff’s promise of a job and found out what their role would be when they arrived in mid-September. Positions were granted on a first-come-first-served basis, with exceptions being made for students that came highly recommended. Students who requested jobs in late August and early September were either turned away or offered half-tuition, depending on the availability.

Unconventional Payments

Even with the generous scholarship and employment opportunities provided by Baylor, access to higher education was still out of reach for many students. In these cases, and typically when asked, Neff allowed for unconventional payments. One example of this was Maxwell Welch, who had “a 100-acre farm… this farm as a four room house, a barn, sixty five acres in cultivation, and thirty five in pastures” (Welch, 1934). The farm was “valued at $2000.00 and has a clear title…with the exception of two or three years back taxes” (Welch, 1934). Welch desperately wanted to study law at Baylor, and Neff agreed to negotiate a trade, citing his own experience: “It reminds me that many years ago, too far back now to give a definite date, I sold a little piece of land I owned to come to Baylor University. I would not trade, not for a million dollars in good money, what Baylor University did for me” (Neff, 1934).

Another type of unconventional payment was an agreement to work for Baylor in exchange for a sibling or child to attend free of charge. In 1933, Cynthia Sory wrote Neff to ask if she could work for Baylor University in exchange for her brother’s tuition. President Neff was open to the option and even offered her the opportunity to do graduate work at Baylor, provided she pay the necessary student fees. This type of payment, was less frequent than student employment and some requests for work of this nature was denied due to lack of available positions.

Pat Neff’s strategic mind led him to negotiate these unusual trades in exchange for tuition, but none is more unusual than W.E. Whigham’s offer to pay for his son’s tuition with grapefruits: “We are like most people in the valley, broke. But we will have plenty or access to plenty of grapefruit this season so we wondered if we could trade it for tuition and board?” (Whigham, 1934). Neff allowed for the grapefruit to pay for tuition and be served in the dormitories, so long as it was traded at regular market price.

Loan Aversion

Perhaps the most interesting factor, is the overall avoidance of going into debt in the name of education. It is obvious, by the multitudes of students offering to work their way through school, that students and parents saw a significant value in attending college. In many cases, however, if the financial aid offered did not sufficiently cover the costs, a regretful letter was written to President Neff thanking him for his help but declining the offer.

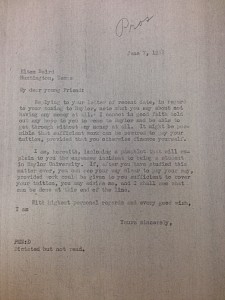

Baylor University did have a loan fund, however, Neff made it clear that it was not for first year students in many of his correspondences. Instead, the loans were made to students who had attended Baylor and needed assistance, typically due to some poor circumstances, in finishing their degree. Then and only then were loans made to students. Neff often discouraged students from attending Baylor without a sufficient financial plan. In a letter to Elton Baird who admitted he had “no money at all,” Neff responded bluntly: “In regard to your coming to Baylor, note what you say about having no money at all. I cannot in good faith hold out any hope to you to come to Baylor and be able to get through without any money at all” (Neff, 1933).

Conclusion

Baylor University, and specifically Pat Neff, worked tirelessly to provide access to students seeking an education during the aftermath of the Great Depression. Education was growing in importance and families and students were willing to sacrifice time, energy, land and grapefruits to have the opportunity for learning and advancement. Neff’s acceptance of these unconventional forms of payment encouraged the pursuit of education while discouraging debt.

References

Back, P. (1933). [Letter from Mrs. Paul Back to Pat M. Neff]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Pat M. Neff Collection. Series 4. Sub-series 3. Box 20. Folder 1. Prospective Student Correspondence: B #1, 1933) Waco, TX.

Barclay, H. (1933). [Letter from Harold Barclay to Pat M. Neff]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Pat M. Neff Collection. Series 4. Sub-series 3. Box 20. Folder 1. Prospective Student Correspondence: B #1, 1933) Waco, TX.

Alphabetical List of Student Employees – Fall 1939. (1939). The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Pat M. Neff Collection. Series 8. Sub-series 2. Box 62. Folder 12. Baylor General Correspondence: Student Employment, 1939 Fall) Waco, TX.

Bernstein, I. (1976). Americans in Depression and War. In The U.S. Department of Labor Bicentennial History of The American Worker [Online version].Retrieved from http:// www.dol.gov/dol/aboutdol/history/chapter5.htm

McCall, A.V. (1933). [Letter from Abner Vernon McCall to Pat M. Neff]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Pat M. Neff Collection. Series 4. Sub-series 3. Box 23. Folder 1. Prospective Student Correspondence: M #1, 1933) Waco, TX.

Neff, P.M. (1933). [Letter from Pat M. Neff to Elton Baird]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Pat M. Neff Collection. Series 4. Sub-series 3. Box 20. Folder 1. Prospective Student Correspondence: B #1, 1933) Waco, TX.

Neff, P.M. (1934). [Letter from Pat M. Neff to Maxwell Welch]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Pat M. Neff Collection. Series 4. Sub-series 3. Sub-subseries 2. Box 39. Folder 1. Prospective Student Correspondence: W (5 of 6), 1934) Waco, TX.

Sory, C. (1933). [Letter from Cynthia Sory to Pat M. Neff]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Pat M. Neff Collection. Series 4. Sub-series 3. Sub-subseries 2. Box 24. Folder 6. Prospective Student Correspondence: S #1 (4 of 4), 1933) Waco, TX.

The Baylor Bulletin. (1934). The Texas Collection at the Carroll Library, Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Welch, M. (1934). [Letter from Maxwell to Pat M. Neff]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Pat M. Neff Collection. Series 4. Sub-series 3. Sub-subseries 2. Box 39. Folder 1. Prospective Student Correspondence: W (5 of 6), 1934) Waco, TX.

Whigham, W.E. (1934). [Letter from W.E. Whigham to Pat M. Neff]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Pat M. Neff Collection. Series 4. Sub-series 3. Sub-subseries 2. Box 39. Folder 1. Prospective Student Correspondence: W (5 of 6), 1934) Waco, TX.