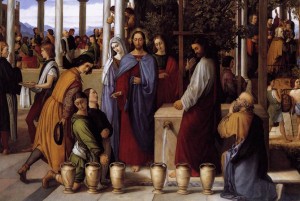

John 2:1-11

This text is used for the Lectionary Year C on January 17, 2016.

There was a reoccurring segment on Sesame Street in which the camera would focus on four items. Three of them would be the same and the fourth, similar in some way, but distinctively different in another. In this reoccurring segment, a song would always accompany the puzzle with the lyrics, “one of these things is not like the others.” That is not a bad way to think about John. John is a gospel and as the other three do, tells the passion of Jesus with an extended introduction. But John is also distinct. Let me point out two the obvious ways in which it is a departure. In the synoptics, Jesus is an advocate of the Kingdom. In John, Jesus is an advocate of Jesus, who is the full revelation of God’s glory. In the synoptics, Jesus preforms miracles, the Greek dynamis. That word means acts of power and it is the word from which we get the word dynamite. In John, Jesus preforms signs, the Greek semeion. Miracles point to the features of the kingdom; signs establish Jesus’ credibility.

John is divided into the “book of signs,” chapter 1:19 – chapter 12, and the “book of glory,” chapters 13-20. The wedding at Cana is the first sign. I gave that long introduction because it is crucial for understanding this otherwise seemingly odd and uniquely Johannine miracle. This story is loaded with symbolic imagery, each of them worthy of extended attention. But what remains most important is that Jesus is establishing credibility and unveiling his nature, which was mapped out for readers in the prologue found in the previous chapter. Wine is very often associated with joy. This sign characterizes the nature of Jesus’ reign. In this regard it is worth noting that the sign is not without eschatological significance. In the beginning of his public ministry, Jesus begins the party that will reach it’s fulfillment in his Eschaton.

When I was becoming acquainted with the lectionary for the first time, I was under the assumption that Epiphany was a season in the same way that Lent and Advent were. I think I had even heard about the theological purpose of Epiphany: it is the season when Christ is unveiled. Eventually my Episcopal friends would gently correct me, pointing out that it is instead the first instance of ordinary time. Still I don’t think that description, wherever I got it from, is half bad. Think about what comes to us in Epiphany in Year C: a baptism, a party, an epic sermon, Jesus’ dedication and the transfiguration. If Mary had put together a scrapbook, it would probably look like Epiphany.

When I was becoming acquainted with the lectionary for the first time, I was under the assumption that Epiphany was a season in the same way that Lent and Advent were. I think I had even heard about the theological purpose of Epiphany: it is the season when Christ is unveiled. Eventually my Episcopal friends would gently correct me, pointing out that it is instead the first instance of ordinary time. Still I don’t think that description, wherever I got it from, is half bad. Think about what comes to us in Epiphany in Year C: a baptism, a party, an epic sermon, Jesus’ dedication and the transfiguration. If Mary had put together a scrapbook, it would probably look like Epiphany. I’m never entirely sure what to do when the lectionary hands me a set of verses, half of which are in parentheses. Does that mean those verses are a suggestion or does it indicate they are less crucial to the liturgical season on hand? Or does the lectionary committee simply mean to honor my skill as a preacher treating me like a quarterback with an ability to call an audible after a quick look at the congregation. “This bunch looks engaged, I think I’ll unpack the cryptic prologue,” or “This group looks like they’ve been to a Christmas party thrown by Christians who’ve found their freedom in Christ, I better stick with the basics.”

I’m never entirely sure what to do when the lectionary hands me a set of verses, half of which are in parentheses. Does that mean those verses are a suggestion or does it indicate they are less crucial to the liturgical season on hand? Or does the lectionary committee simply mean to honor my skill as a preacher treating me like a quarterback with an ability to call an audible after a quick look at the congregation. “This bunch looks engaged, I think I’ll unpack the cryptic prologue,” or “This group looks like they’ve been to a Christmas party thrown by Christians who’ve found their freedom in Christ, I better stick with the basics.”