What is in “A Face”?

Robert Browning’s poem “A Face” (published 1864) was written in response to Coventry Patmore’s The Angel in the House. While published in 1864, the poem was written by Robert twelve years earlier for Ms. Emily Patmore, wife and muse of Coventry Patmore’s The Angel in the House, a poem that celebrates questionable Victorian standards of beauty. Although this poem was written roughly 100 years ago, the importance of beauty is considered just as valuable today as it was in Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s time.

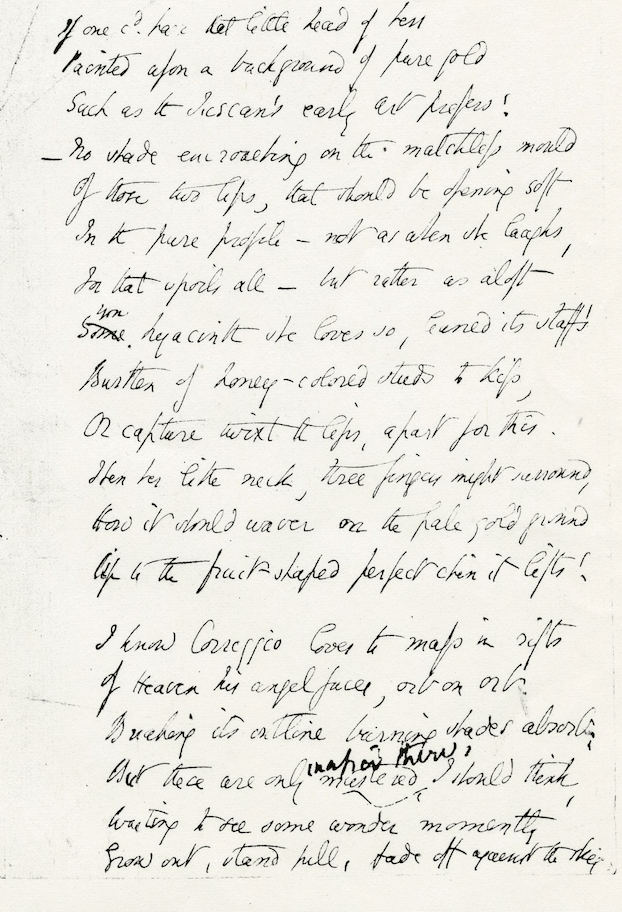

The pictured manuscript (left) was copied out by Elizabeth, perhaps around the time that Robert gave it to Emily. Robert corrected it around 1864 before publishing the poem, and then later gave it to a friend, Mrs. Fitzgerald, in 1874. The importance of one’s defining facial features paints the image of Victorian beauty. Elizabeth, who often struggled with the importance placed on beauty, wrote her own thoughts on beauty differently than that of Robert and of Coventry Patmore.

For example, look at first through seventh lines of “A Face”:

“If one could have that little head of hers

Painted upon a background of pale gold,

Such as the Tuscan’s early art prefers!

No shade encroaching on the matchless mould

Of those two lips, which should be opening soft

In the pure profile; not as when she laughs,

For that spoils all…”

Compare to this passage about Elizabeth’s own thoughts on beauty,

“Can Women only triumph in the sigh,

The smile coquettish, or bewitching eye?

Are drawing words, & affectious airs

The only claim on notice that are hers.”

Elizabeth often criticized treatment of women as pleasing objects for men, as in her major poem, Aurora Leigh (published 1856). This concept is not unfamiliar today as many women still hope to be credited for their work ethic over their appearance. Elizabeth’s and Robert’s work is still resonating in society today.

Exhibit created by Gabriela Aguilar

John Singer Sargent’s oil painting of Coventry Patmore, 1894.

In his poem, Coventry described his wife, Emily, with heavenly qualities as we see below:

“The best things that the best believe

Are in her face so brightly writ

The faithless, seeing her, conceive

Not only heaven, but hope of it.”

Coventry turns Emily into an image of otherworldly beauty, an angelic muse, with little attention to her own agency.

John Brett’s oil painting of Mrs. Coventry Patmore, 1856.

Coventry turned his wife into an icon of domestic beauty, but Emily Patmore was far more than a face. She was a critic, a poet, and an accomplished writer. Much like Elizabeth and Robert, Coventry and Emily were writers and critics towards one another, a marriage of equals. It is unfortunate that Emily’s work is overshadowed by her beauty while she had much more to contribute.

Photograph of Louis Cyrus Macaire and Jean Victor Macaire-Warnod’s 1858 ambrotype of Elizabeth Barrett Browning by Elliot & Frye, 1858.

Elizabeth often wrote about the issues surrounding women in the Victorian era, and, while society has come forward in time, there are still more steps to take. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s life and achievements are fundamental pieces in women’s history. Elizabeth’s success as a writer supersedes her beauty. My colleagues will showcase the importance of not only her works but of Robert Browning’s works, and their hunt to make society understanding and developed for the better.

Recent Comments