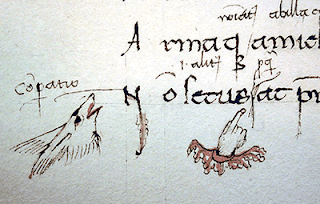

While doing a little work yesterday, I accidentally skinned the back of my index finger on my right hand. Now I have a scab there which has been unceremoniously ripped off about five times, and this is the skin on the knuckle, on the back of the finger. You never know how much you use that particular finger until you have to do dishes, floss, tie your shoes, or change your the tail pipe on your muffler. Even drinking coffee is strange now because that particular spot on the finger touches the hot cup, which I did not know until this morning. Some people call it the “pointer” finger, which sounds rude and probably is. Yet, even from medieval times the “indice” was known as that finger which everyone uses to give directions and focus the attention of different speech acts. And scratching (if you deny you scratch, you really need to have your head examined), who could get through a day without scratching? We won’t specify what, but scratching is important, especially if you have an itch. Even pictures of a hand pointing with its index finger extended have been important signs centuries. Today we might substitute an arrow or similar icon, but it’s just a variant of the pointing finger. Most people “mouse” with their index finger, and those who never learned to type properly use their index fingers to communicate with the world. And there are those less delicate people who think they are invisible at a stop light while they use their index finger to pick their noses. The light turns red, and the old index finger goes into action like an ancient coal miner who just found a new vein to mine. The finger that we wag at our opponents is also the finger with which we push buttons, which may be one and the same thing, depending how who you are trying to bother. For some, the index is also their trigger finger, which is interesting but not necessarily telling or indicative of anything. Until, however, you have an “owie” on it, you just never realize how important that little digit really is.

Category Archives: Weird rant

On hurting your index finger

While doing a little work yesterday, I accidentally skinned the back of my index finger on my right hand. Now I have a scab there which has been unceremoniously ripped off about five times, and this is the skin on the knuckle, on the back of the finger. You never know how much you use that particular finger until you have to do dishes, floss, tie your shoes, or change your the tail pipe on your muffler. Even drinking coffee is strange now because that particular spot on the finger touches the hot cup, which I did not know until this morning. Some people call it the “pointer” finger, which sounds rude and probably is. Yet, even from medieval times the “indice” was known as that finger which everyone uses to give directions and focus the attention of different speech acts. And scratching (if you deny you scratch, you really need to have your head examined), who could get through a day without scratching? We won’t specify what, but scratching is important, especially if you have an itch. Even pictures of a hand pointing with its index finger extended have been important signs centuries. Today we might substitute an arrow or similar icon, but it’s just a variant of the pointing finger. Most people “mouse” with their index finger, and those who never learned to type properly use their index fingers to communicate with the world. And there are those less delicate people who think they are invisible at a stop light while they use their index finger to pick their noses. The light turns red, and the old index finger goes into action like an ancient coal miner who just found a new vein to mine. The finger that we wag at our opponents is also the finger with which we push buttons, which may be one and the same thing, depending how who you are trying to bother. For some, the index is also their trigger finger, which is interesting but not necessarily telling or indicative of anything. Until, however, you have an “owie” on it, you just never realize how important that little digit really is.

On parade floats

Does anyone other than myself think that parade floats are a very strange cultural phenomenon? As a five-year-old I was fascinated by the floats in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade or in the New Year’s Parade out in Pasadena with all those red roses. My first experience with a float, up close and personal, was a float built by a fraternity from the local college. I got to play with the gold and black crepe paper, which is very cool if you are five. I know that homecoming floats are about school spirit, or that a Thanksgiving Day float is all about Santa Claus, but other than putting some pretty girls or some little kids on a float, I have no idea what the social function of a float is. Are we celebrating something or commemorating something? And if we are, why? One fraternity I know of builds an anti-float, which is just a flatbed truck with a bunch of broken down sofas on it. Would that be the example of an iconoclastic float? Or an anarchy float? I have never built a float, nor do I understand float lore or craft. I suppose floats need to be thematic, have paper mache caricatures of self-important political figures, sport several winsome lasses, threaten the opposing team with some soporific metaphor concerning destruction and loss, and sport the conquering team’s mascot. Or children. Or Santa Claus. Or a strange dancing group. Today I’m even more concerned than ever that I still do not understand the cultural materialism involved in the grotesque manifestation of school, team, or city spirit. Floats are a very public spectacle designed to draw attention to something, but they are still a short-lived, transitory, if not temporary, simulacra of life designed of materials with a limited life-span, so in a real sense, they are ephemera.

On parade floats

Does anyone other than myself think that parade floats are a very strange cultural phenomenon? As a five-year-old I was fascinated by the floats in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade or in the New Year’s Parade out in Pasadena with all those red roses. My first experience with a float, up close and personal, was a float built by a fraternity from the local college. I got to play with the gold and black crepe paper, which is very cool if you are five. I know that homecoming floats are about school spirit, or that a Thanksgiving Day float is all about Santa Claus, but other than putting some pretty girls or some little kids on a float, I have no idea what the social function of a float is. Are we celebrating something or commemorating something? And if we are, why? One fraternity I know of builds an anti-float, which is just a flatbed truck with a bunch of broken down sofas on it. Would that be the example of an iconoclastic float? Or an anarchy float? I have never built a float, nor do I understand float lore or craft. I suppose floats need to be thematic, have paper mache caricatures of self-important political figures, sport several winsome lasses, threaten the opposing team with some soporific metaphor concerning destruction and loss, and sport the conquering team’s mascot. Or children. Or Santa Claus. Or a strange dancing group. Today I’m even more concerned than ever that I still do not understand the cultural materialism involved in the grotesque manifestation of school, team, or city spirit. Floats are a very public spectacle designed to draw attention to something, but they are still a short-lived, transitory, if not temporary, simulacra of life designed of materials with a limited life-span, so in a real sense, they are ephemera.

On groovy

For those of you who did not grow up in the nineteen sixties, this word is nothing but a strange artifact of that lost decade. Groovy was the paradigm for a generation whose youth was lost in the maelstrom of assassinations, war, protests, draft cards, sit-ins, rock’n roll, peace signs, ecology, weed, Charlie Manson, the Beatles, and a whole raft of strange sitcoms on the television. It was the younger generation–the Hippies–who started to use the word to describe either things they liked or what made them happy, which wasn’t much during the sixties. Born in ’59 to the Eisenhower and Formica generation, I was a little boy during the “groovy” years, which were culminated by the election of Nixon in ’68 and the moon-landing in the summer of ’69. Whenever I heard the word used, or whenever I tried to the use the word, I always felt like everything was incredibly phony. I mean, I never lived in a commune, never smoked or took dope, never burned a draft card, or took part in a riot–I was just a kid. If one of the Monkeys or John Denver said, “Groovy,” I always felt like I was left out, like I didn’t get the joke, that I didn’t understand what the word meant. To this day, I’ve always felt like the word contained an edge of irony or violence that was contrary to what people thought the word meant. It’s as if the word was a self-contained parody of a word, that to use it, you were subjecting yourself to self-parody, ending up with egg on your face, foolish, as if you didn’t really know what groovy meant either. You see, the sixties were many things, but they were never “groovy.” Flower power, Mary Jane, the Cold War, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, Detroit, Watts, Birmingham, Saigon, Paris, and the list could go on and on. For a child there was very little that was actually groovy in the conflicts that marked a decade that was filled with death, destruction, and random violence that seemed both common and mundane. Groovy did not seem to be the right word to describe the generation gap, psychedelic drugs such as LSD and marijuana, the fight for civil rights, the war in Vietnam, or the generalized pollution that contaminated our lakes, rivers, and air. We started to wear bell-bottoms and tie-dyed t-shirts. Although I still think tie-dyed t-shirts are rather groovy–I hate bell-bottoms. Although long hair is rather groovy, it never looked good on me. The sixties left me feeling empty, as if nothing were ever very groovy for me. I was growing up in middle America, small town, very agrarian, as if it were impossible to really ever escape the 1890’s, which was when the house I grew up in was built. I was about as far from “groovy” as any one person might get. Perhaps the essence of “groovy” resides in the changing paradigm of lost innocence that marked those years as our country slowly burned in the fire of urban violence and jungle warfare. When the sixties were over, and before Watergate started to garner all the newspaper coverage, “groovy” just passed away, a weird leftover relic of a strange and unsettling decade of the Domino Effect, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Tonkin Gulf incident, Mi Lai, Robert Kennedy and all the rest of the un-groovy disasters that filled our lives and made headlines every night. Let’s not forget the dead report given by Walter Cronkite each night as he recounted the wounded, dead, and missing–nothing less groovy than that. Does anyone really know what “groovy” means anyway?

On groovy

For those of you who did not grow up in the nineteen sixties, this word is nothing but a strange artifact of that lost decade. Groovy was the paradigm for a generation whose youth was lost in the maelstrom of assassinations, war, protests, draft cards, sit-ins, rock’n roll, peace signs, ecology, weed, Charlie Manson, the Beatles, and a whole raft of strange sitcoms on the television. It was the younger generation–the Hippies–who started to use the word to describe either things they liked or what made them happy, which wasn’t much during the sixties. Born in ’59 to the Eisenhower and Formica generation, I was a little boy during the “groovy” years, which were culminated by the election of Nixon in ’68 and the moon-landing in the summer of ’69. Whenever I heard the word used, or whenever I tried to the use the word, I always felt like everything was incredibly phony. I mean, I never lived in a commune, never smoked or took dope, never burned a draft card, or took part in a riot–I was just a kid. If one of the Monkeys or John Denver said, “Groovy,” I always felt like I was left out, like I didn’t get the joke, that I didn’t understand what the word meant. To this day, I’ve always felt like the word contained an edge of irony or violence that was contrary to what people thought the word meant. It’s as if the word was a self-contained parody of a word, that to use it, you were subjecting yourself to self-parody, ending up with egg on your face, foolish, as if you didn’t really know what groovy meant either. You see, the sixties were many things, but they were never “groovy.” Flower power, Mary Jane, the Cold War, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, Detroit, Watts, Birmingham, Saigon, Paris, and the list could go on and on. For a child there was very little that was actually groovy in the conflicts that marked a decade that was filled with death, destruction, and random violence that seemed both common and mundane. Groovy did not seem to be the right word to describe the generation gap, psychedelic drugs such as LSD and marijuana, the fight for civil rights, the war in Vietnam, or the generalized pollution that contaminated our lakes, rivers, and air. We started to wear bell-bottoms and tie-dyed t-shirts. Although I still think tie-dyed t-shirts are rather groovy–I hate bell-bottoms. Although long hair is rather groovy, it never looked good on me. The sixties left me feeling empty, as if nothing were ever very groovy for me. I was growing up in middle America, small town, very agrarian, as if it were impossible to really ever escape the 1890’s, which was when the house I grew up in was built. I was about as far from “groovy” as any one person might get. Perhaps the essence of “groovy” resides in the changing paradigm of lost innocence that marked those years as our country slowly burned in the fire of urban violence and jungle warfare. When the sixties were over, and before Watergate started to garner all the newspaper coverage, “groovy” just passed away, a weird leftover relic of a strange and unsettling decade of the Domino Effect, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Tonkin Gulf incident, Mi Lai, Robert Kennedy and all the rest of the un-groovy disasters that filled our lives and made headlines every night. Let’s not forget the dead report given by Walter Cronkite each night as he recounted the wounded, dead, and missing–nothing less groovy than that. Does anyone really know what “groovy” means anyway?

On email

How can something so useful be such a pain in the ass? I imagine email is probably a question of boundaries–when at work, use it as a tool to solve problems, when you are at home, don’t look at it at all or it will take over your life, eat you alive. Some people like to use massive emails to hurt and intimidate others because you really can’t win an argument over email, and if you do argue over email, you are just as foolish as the person with whom you are arguing. Emails from vendors are annoying, and I frequently erase almost all of them without even opening them. Junk email is just weird foolishness. I wish student would observe even a modicum of formality in their emails–I am not a friend or family member to whom they might send just any old thing. Given that it takes time to sort out what someone wants in their email, people should be more careful when they write their email. The first question I would ask is, is email the best way to handle whatever might be in play? And I would never write an email unless I wouldn’t mind seeing its contents on the front page of the Dallas Morning News. Nobody should even think of emailing anyone about anything if they are under the influence of intoxicating beverages. Email is the ideal place to get a good rumor going or to really mess up a good relationship by writing an ambiguous or easily misunderstood message. I think it all goes back to two things: is this email really necessary and how bad are my writing skills. The problem with the language in an email is that we spend so little time writing it that we are prone to simple errors and misunderstandings. The only thing worse than bad writing is bad reading, and if we spend almost no time writing an email, we spend even less reading one. All of this “speed” is a recipe for disaster. I write fast, you read fast, we haven’t the slightest clue as to what has happened, but we can be certain that good communication has not occurred. Trying to solve a complicated problem via email is a total disaster. Digitally mediated communication is an open invitation to miscommunication. Email is frequently the coward’s way making their cowardly opinion known to all. It’s a lot like striking someone from behind and then hiding your hand as if you were innocent. The most annoying thing in email, besides junk email, are jokes that get forwarded to you via friends and family who mean well, but have no idea how insulting and stupid their jokes are. There are a lot of “inappropriate” jokes out there which racist, sexist, biased, and insensitive, and I just don’t need any of that cluttering up my inbox, which is always full anyway. I don’t need a lot of useless crap cluttering up my already full inbox. Email should be a tool by which you spread useful information to students: announcements, syllabi, deadlines, explanations. It should not be someone’s personal soapbox from which they express a lot of hateful or hurtful opinions. So I have this love/hate thing going with my email. I know which kinds of things should never be written, not even in jest, but I also see the utility of sending out useful information to an entire list of students who might be traveling to Spain this summer. What I cannot expect, especially in summer, is that people will always answer an email right away. Since I am apt to answer an email almost right away, I am frequently disappointed when my emails go unanswered. Email is just fraught with difficulties, problems, ambiguities, and failure. Writing emails in which you complain about anything is just a waste of time, and may get you fired in the meantime. Email can be so problematic that I refuse to solve any human problem by just sending an email. If I have to deliver bad news, it’s always best to do it in person. Now, if you want to have coffee, you may invite me via email. When I see forty-five unanswered emails in my inbox, I just cringe and wonder what I did to deserve this. Is there a morale to this story? Probably not, except that the next time you decide to write an email, I hope you think twice before doing it.

How can something so useful be such a pain in the ass? I imagine email is probably a question of boundaries–when at work, use it as a tool to solve problems, when you are at home, don’t look at it at all or it will take over your life, eat you alive. Some people like to use massive emails to hurt and intimidate others because you really can’t win an argument over email, and if you do argue over email, you are just as foolish as the person with whom you are arguing. Emails from vendors are annoying, and I frequently erase almost all of them without even opening them. Junk email is just weird foolishness. I wish student would observe even a modicum of formality in their emails–I am not a friend or family member to whom they might send just any old thing. Given that it takes time to sort out what someone wants in their email, people should be more careful when they write their email. The first question I would ask is, is email the best way to handle whatever might be in play? And I would never write an email unless I wouldn’t mind seeing its contents on the front page of the Dallas Morning News. Nobody should even think of emailing anyone about anything if they are under the influence of intoxicating beverages. Email is the ideal place to get a good rumor going or to really mess up a good relationship by writing an ambiguous or easily misunderstood message. I think it all goes back to two things: is this email really necessary and how bad are my writing skills. The problem with the language in an email is that we spend so little time writing it that we are prone to simple errors and misunderstandings. The only thing worse than bad writing is bad reading, and if we spend almost no time writing an email, we spend even less reading one. All of this “speed” is a recipe for disaster. I write fast, you read fast, we haven’t the slightest clue as to what has happened, but we can be certain that good communication has not occurred. Trying to solve a complicated problem via email is a total disaster. Digitally mediated communication is an open invitation to miscommunication. Email is frequently the coward’s way making their cowardly opinion known to all. It’s a lot like striking someone from behind and then hiding your hand as if you were innocent. The most annoying thing in email, besides junk email, are jokes that get forwarded to you via friends and family who mean well, but have no idea how insulting and stupid their jokes are. There are a lot of “inappropriate” jokes out there which racist, sexist, biased, and insensitive, and I just don’t need any of that cluttering up my inbox, which is always full anyway. I don’t need a lot of useless crap cluttering up my already full inbox. Email should be a tool by which you spread useful information to students: announcements, syllabi, deadlines, explanations. It should not be someone’s personal soapbox from which they express a lot of hateful or hurtful opinions. So I have this love/hate thing going with my email. I know which kinds of things should never be written, not even in jest, but I also see the utility of sending out useful information to an entire list of students who might be traveling to Spain this summer. What I cannot expect, especially in summer, is that people will always answer an email right away. Since I am apt to answer an email almost right away, I am frequently disappointed when my emails go unanswered. Email is just fraught with difficulties, problems, ambiguities, and failure. Writing emails in which you complain about anything is just a waste of time, and may get you fired in the meantime. Email can be so problematic that I refuse to solve any human problem by just sending an email. If I have to deliver bad news, it’s always best to do it in person. Now, if you want to have coffee, you may invite me via email. When I see forty-five unanswered emails in my inbox, I just cringe and wonder what I did to deserve this. Is there a morale to this story? Probably not, except that the next time you decide to write an email, I hope you think twice before doing it.

On email

How can something so useful be such a pain in the ass? I imagine email is probably a question of boundaries–when at work, use it as a tool to solve problems, when you are at home, don’t look at it at all or it will take over your life, eat you alive. Some people like to use massive emails to hurt and intimidate others because you really can’t win an argument over email, and if you do argue over email, you are just as foolish as the person with whom you are arguing. Emails from vendors are annoying, and I frequently erase almost all of them without even opening them. Junk email is just weird foolishness. I wish student would observe even a modicum of formality in their emails–I am not a friend or family member to whom they might send just any old thing. Given that it takes time to sort out what someone wants in their email, people should be more careful when they write their email. The first question I would ask is, is email the best way to handle whatever might be in play? And I would never write an email unless I wouldn’t mind seeing its contents on the front page of the Dallas Morning News. Nobody should even think of emailing anyone about anything if they are under the influence of intoxicating beverages. Email is the ideal place to get a good rumor going or to really mess up a good relationship by writing an ambiguous or easily misunderstood message. I think it all goes back to two things: is this email really necessary and how bad are my writing skills. The problem with the language in an email is that we spend so little time writing it that we are prone to simple errors and misunderstandings. The only thing worse than bad writing is bad reading, and if we spend almost no time writing an email, we spend even less reading one. All of this “speed” is a recipe for disaster. I write fast, you read fast, we haven’t the slightest clue as to what has happened, but we can be certain that good communication has not occurred. Trying to solve a complicated problem via email is a total disaster. Digitally mediated communication is an open invitation to miscommunication. Email is frequently the coward’s way making their cowardly opinion known to all. It’s a lot like striking someone from behind and then hiding your hand as if you were innocent. The most annoying thing in email, besides junk email, are jokes that get forwarded to you via friends and family who mean well, but have no idea how insulting and stupid their jokes are. There are a lot of “inappropriate” jokes out there which racist, sexist, biased, and insensitive, and I just don’t need any of that cluttering up my inbox, which is always full anyway. I don’t need a lot of useless crap cluttering up my already full inbox. Email should be a tool by which you spread useful information to students: announcements, syllabi, deadlines, explanations. It should not be someone’s personal soapbox from which they express a lot of hateful or hurtful opinions. So I have this love/hate thing going with my email. I know which kinds of things should never be written, not even in jest, but I also see the utility of sending out useful information to an entire list of students who might be traveling to Spain this summer. What I cannot expect, especially in summer, is that people will always answer an email right away. Since I am apt to answer an email almost right away, I am frequently disappointed when my emails go unanswered. Email is just fraught with difficulties, problems, ambiguities, and failure. Writing emails in which you complain about anything is just a waste of time, and may get you fired in the meantime. Email can be so problematic that I refuse to solve any human problem by just sending an email. If I have to deliver bad news, it’s always best to do it in person. Now, if you want to have coffee, you may invite me via email. When I see forty-five unanswered emails in my inbox, I just cringe and wonder what I did to deserve this. Is there a morale to this story? Probably not, except that the next time you decide to write an email, I hope you think twice before doing it.

How can something so useful be such a pain in the ass? I imagine email is probably a question of boundaries–when at work, use it as a tool to solve problems, when you are at home, don’t look at it at all or it will take over your life, eat you alive. Some people like to use massive emails to hurt and intimidate others because you really can’t win an argument over email, and if you do argue over email, you are just as foolish as the person with whom you are arguing. Emails from vendors are annoying, and I frequently erase almost all of them without even opening them. Junk email is just weird foolishness. I wish student would observe even a modicum of formality in their emails–I am not a friend or family member to whom they might send just any old thing. Given that it takes time to sort out what someone wants in their email, people should be more careful when they write their email. The first question I would ask is, is email the best way to handle whatever might be in play? And I would never write an email unless I wouldn’t mind seeing its contents on the front page of the Dallas Morning News. Nobody should even think of emailing anyone about anything if they are under the influence of intoxicating beverages. Email is the ideal place to get a good rumor going or to really mess up a good relationship by writing an ambiguous or easily misunderstood message. I think it all goes back to two things: is this email really necessary and how bad are my writing skills. The problem with the language in an email is that we spend so little time writing it that we are prone to simple errors and misunderstandings. The only thing worse than bad writing is bad reading, and if we spend almost no time writing an email, we spend even less reading one. All of this “speed” is a recipe for disaster. I write fast, you read fast, we haven’t the slightest clue as to what has happened, but we can be certain that good communication has not occurred. Trying to solve a complicated problem via email is a total disaster. Digitally mediated communication is an open invitation to miscommunication. Email is frequently the coward’s way making their cowardly opinion known to all. It’s a lot like striking someone from behind and then hiding your hand as if you were innocent. The most annoying thing in email, besides junk email, are jokes that get forwarded to you via friends and family who mean well, but have no idea how insulting and stupid their jokes are. There are a lot of “inappropriate” jokes out there which racist, sexist, biased, and insensitive, and I just don’t need any of that cluttering up my inbox, which is always full anyway. I don’t need a lot of useless crap cluttering up my already full inbox. Email should be a tool by which you spread useful information to students: announcements, syllabi, deadlines, explanations. It should not be someone’s personal soapbox from which they express a lot of hateful or hurtful opinions. So I have this love/hate thing going with my email. I know which kinds of things should never be written, not even in jest, but I also see the utility of sending out useful information to an entire list of students who might be traveling to Spain this summer. What I cannot expect, especially in summer, is that people will always answer an email right away. Since I am apt to answer an email almost right away, I am frequently disappointed when my emails go unanswered. Email is just fraught with difficulties, problems, ambiguities, and failure. Writing emails in which you complain about anything is just a waste of time, and may get you fired in the meantime. Email can be so problematic that I refuse to solve any human problem by just sending an email. If I have to deliver bad news, it’s always best to do it in person. Now, if you want to have coffee, you may invite me via email. When I see forty-five unanswered emails in my inbox, I just cringe and wonder what I did to deserve this. Is there a morale to this story? Probably not, except that the next time you decide to write an email, I hope you think twice before doing it.

On divination

All divination is just so much malarky. All due respect for the Divination class at Hogwarts for which none of the other professors have any respect, by the way, but divination is a lot of hogwash, meaningless, empty, wrong, void. I think it is very telling that even in the fictional world of Harry Potter, characters which believe in and perform magic do not believe in divination, reading tea leaves, looking into crystal balls, signs, reading palms, tarot, bones, shooting stars, or anything else that might be read or construed as a sign of things to come. In Spain’s 13th century, divination was a real problem because there was so little difference between what might be understood as science and what might be understood as pseudo-science–astrology, quiromancia, necromancia, fortune-telling, and a host of other “mancias” which followed everything from the shape of a dog turd to random feathers found on a street. Black cats, scorpions, bats, goats, any horned animal, a white dove, unicorns were considered in turn to be good, bad, evil, a blessing, all of which is completely meaningless. Unless you find lots of bugs in your house, which might mean you need to take out the trash more often and clean, but this has more to do with deduction and nothing to do with divination. The planets do not guide anyone’s future, and their arbitrary alignment at your birth has nothing to do with who you are as a person. Perhaps I understand why people struggle with divination. Given the chaotic and unstable nature of life, we all want to know what is happening tomorrow–should we invest, look for a new job, buy a new house, get married, have children, break up, undertake a new project, accept a new position, advise someone on their uncertain future? Yet, the future is an unwritten script and will be ruled by the millions and millions of decisions which are made at any given moment as we move forward. The idea that the future is chaotic and unknowable makes people uncomfortable, but the markets will go up and down, students will fail or succeed, couples will get married and breakup, you will make mistakes or your plans will finally come to fruition, but all of that will happen not because you don’t know what will happen, but because you work hard now to make things happen and come true. Everyday, however, people throw away hard-earned money to consult charlatans, quacks, and thieves who have convinced them that they can tell them the future. Predictions are general, over-reaching, non-specific, and the victims (or fools) fill in the blanks, thinking that they have finally found someone who can really tell the future. Why is it, then, that psychics never win the lottery? All psychics are phony, false, criminals. All divination is dishonest. No one has a gift, and all attempts to prove otherwise have proved that things such as ESP don’t exist outside of what is statistically possible to predict. The fact that my colleagues in the 13th century had to wade through such a morass of conmen, fakes, phonies, charlatans is disheartening because the difference between science and non-science was confusing and unclear. No one had the great scientific vision of a Bacon or a Galileo. Questions of mystic visions or psychic revelations, diabolic incantations or black masses, necromancy or palmistry were everywhere because there was no scientific paradigm or orderly scientific method against which these weird and meaningless practices could be debunked. Even today, however, it is mind-blowing that so many people still waste their time and money with these empty and foolish practices. The future cannot be predicted, divined, or foretold–end of story.

All divination is just so much malarky. All due respect for the Divination class at Hogwarts for which none of the other professors have any respect, by the way, but divination is a lot of hogwash, meaningless, empty, wrong, void. I think it is very telling that even in the fictional world of Harry Potter, characters which believe in and perform magic do not believe in divination, reading tea leaves, looking into crystal balls, signs, reading palms, tarot, bones, shooting stars, or anything else that might be read or construed as a sign of things to come. In Spain’s 13th century, divination was a real problem because there was so little difference between what might be understood as science and what might be understood as pseudo-science–astrology, quiromancia, necromancia, fortune-telling, and a host of other “mancias” which followed everything from the shape of a dog turd to random feathers found on a street. Black cats, scorpions, bats, goats, any horned animal, a white dove, unicorns were considered in turn to be good, bad, evil, a blessing, all of which is completely meaningless. Unless you find lots of bugs in your house, which might mean you need to take out the trash more often and clean, but this has more to do with deduction and nothing to do with divination. The planets do not guide anyone’s future, and their arbitrary alignment at your birth has nothing to do with who you are as a person. Perhaps I understand why people struggle with divination. Given the chaotic and unstable nature of life, we all want to know what is happening tomorrow–should we invest, look for a new job, buy a new house, get married, have children, break up, undertake a new project, accept a new position, advise someone on their uncertain future? Yet, the future is an unwritten script and will be ruled by the millions and millions of decisions which are made at any given moment as we move forward. The idea that the future is chaotic and unknowable makes people uncomfortable, but the markets will go up and down, students will fail or succeed, couples will get married and breakup, you will make mistakes or your plans will finally come to fruition, but all of that will happen not because you don’t know what will happen, but because you work hard now to make things happen and come true. Everyday, however, people throw away hard-earned money to consult charlatans, quacks, and thieves who have convinced them that they can tell them the future. Predictions are general, over-reaching, non-specific, and the victims (or fools) fill in the blanks, thinking that they have finally found someone who can really tell the future. Why is it, then, that psychics never win the lottery? All psychics are phony, false, criminals. All divination is dishonest. No one has a gift, and all attempts to prove otherwise have proved that things such as ESP don’t exist outside of what is statistically possible to predict. The fact that my colleagues in the 13th century had to wade through such a morass of conmen, fakes, phonies, charlatans is disheartening because the difference between science and non-science was confusing and unclear. No one had the great scientific vision of a Bacon or a Galileo. Questions of mystic visions or psychic revelations, diabolic incantations or black masses, necromancy or palmistry were everywhere because there was no scientific paradigm or orderly scientific method against which these weird and meaningless practices could be debunked. Even today, however, it is mind-blowing that so many people still waste their time and money with these empty and foolish practices. The future cannot be predicted, divined, or foretold–end of story.

On divination

All divination is just so much malarky. All due respect for the Divination class at Hogwarts for which none of the other professors have any respect, by the way, but divination is a lot of hogwash, meaningless, empty, wrong, void. I think it is very telling that even in the fictional world of Harry Potter, characters which believe in and perform magic do not believe in divination, reading tea leaves, looking into crystal balls, signs, reading palms, tarot, bones, shooting stars, or anything else that might be read or construed as a sign of things to come. In Spain’s 13th century, divination was a real problem because there was so little difference between what might be understood as science and what might be understood as pseudo-science–astrology, quiromancia, necromancia, fortune-telling, and a host of other “mancias” which followed everything from the shape of a dog turd to random feathers found on a street. Black cats, scorpions, bats, goats, any horned animal, a white dove, unicorns were considered in turn to be good, bad, evil, a blessing, all of which is completely meaningless. Unless you find lots of bugs in your house, which might mean you need to take out the trash more often and clean, but this has more to do with deduction and nothing to do with divination. The planets do not guide anyone’s future, and their arbitrary alignment at your birth has nothing to do with who you are as a person. Perhaps I understand why people struggle with divination. Given the chaotic and unstable nature of life, we all want to know what is happening tomorrow–should we invest, look for a new job, buy a new house, get married, have children, break up, undertake a new project, accept a new position, advise someone on their uncertain future? Yet, the future is an unwritten script and will be ruled by the millions and millions of decisions which are made at any given moment as we move forward. The idea that the future is chaotic and unknowable makes people uncomfortable, but the markets will go up and down, students will fail or succeed, couples will get married and breakup, you will make mistakes or your plans will finally come to fruition, but all of that will happen not because you don’t know what will happen, but because you work hard now to make things happen and come true. Everyday, however, people throw away hard-earned money to consult charlatans, quacks, and thieves who have convinced them that they can tell them the future. Predictions are general, over-reaching, non-specific, and the victims (or fools) fill in the blanks, thinking that they have finally found someone who can really tell the future. Why is it, then, that psychics never win the lottery? All psychics are phony, false, criminals. All divination is dishonest. No one has a gift, and all attempts to prove otherwise have proved that things such as ESP don’t exist outside of what is statistically possible to predict. The fact that my colleagues in the 13th century had to wade through such a morass of conmen, fakes, phonies, charlatans is disheartening because the difference between science and non-science was confusing and unclear. No one had the great scientific vision of a Bacon or a Galileo. Questions of mystic visions or psychic revelations, diabolic incantations or black masses, necromancy or palmistry were everywhere because there was no scientific paradigm or orderly scientific method against which these weird and meaningless practices could be debunked. Even today, however, it is mind-blowing that so many people still waste their time and money with these empty and foolish practices. The future cannot be predicted, divined, or foretold–end of story.

All divination is just so much malarky. All due respect for the Divination class at Hogwarts for which none of the other professors have any respect, by the way, but divination is a lot of hogwash, meaningless, empty, wrong, void. I think it is very telling that even in the fictional world of Harry Potter, characters which believe in and perform magic do not believe in divination, reading tea leaves, looking into crystal balls, signs, reading palms, tarot, bones, shooting stars, or anything else that might be read or construed as a sign of things to come. In Spain’s 13th century, divination was a real problem because there was so little difference between what might be understood as science and what might be understood as pseudo-science–astrology, quiromancia, necromancia, fortune-telling, and a host of other “mancias” which followed everything from the shape of a dog turd to random feathers found on a street. Black cats, scorpions, bats, goats, any horned animal, a white dove, unicorns were considered in turn to be good, bad, evil, a blessing, all of which is completely meaningless. Unless you find lots of bugs in your house, which might mean you need to take out the trash more often and clean, but this has more to do with deduction and nothing to do with divination. The planets do not guide anyone’s future, and their arbitrary alignment at your birth has nothing to do with who you are as a person. Perhaps I understand why people struggle with divination. Given the chaotic and unstable nature of life, we all want to know what is happening tomorrow–should we invest, look for a new job, buy a new house, get married, have children, break up, undertake a new project, accept a new position, advise someone on their uncertain future? Yet, the future is an unwritten script and will be ruled by the millions and millions of decisions which are made at any given moment as we move forward. The idea that the future is chaotic and unknowable makes people uncomfortable, but the markets will go up and down, students will fail or succeed, couples will get married and breakup, you will make mistakes or your plans will finally come to fruition, but all of that will happen not because you don’t know what will happen, but because you work hard now to make things happen and come true. Everyday, however, people throw away hard-earned money to consult charlatans, quacks, and thieves who have convinced them that they can tell them the future. Predictions are general, over-reaching, non-specific, and the victims (or fools) fill in the blanks, thinking that they have finally found someone who can really tell the future. Why is it, then, that psychics never win the lottery? All psychics are phony, false, criminals. All divination is dishonest. No one has a gift, and all attempts to prove otherwise have proved that things such as ESP don’t exist outside of what is statistically possible to predict. The fact that my colleagues in the 13th century had to wade through such a morass of conmen, fakes, phonies, charlatans is disheartening because the difference between science and non-science was confusing and unclear. No one had the great scientific vision of a Bacon or a Galileo. Questions of mystic visions or psychic revelations, diabolic incantations or black masses, necromancy or palmistry were everywhere because there was no scientific paradigm or orderly scientific method against which these weird and meaningless practices could be debunked. Even today, however, it is mind-blowing that so many people still waste their time and money with these empty and foolish practices. The future cannot be predicted, divined, or foretold–end of story.