Have you ever woken up to find you had missed the end of the movie or show? Not that it happens often, but sometimes a long day can take its toll on my ability to focus and stay awake. You don’t even know it, really, until it happens: All of a sudden you are looking at and listening to other characters doing other things and you are wondering what happened to the show you were watching. Perhaps I’ve seen way too much television, perhaps I can predict almost any plot twist possible, perhaps I need my sleep more than I need to watch another police procedural show. Yet, it makes me mad to miss the end of the show–I want to find out who did it. It makes me mad that I couldn’t stay awake long enough to make it to the end of an hour show. By falling asleep I am reconfirming that most television is only sleep-worthy and that we are all wasting our time with most of what’s on the tube. By falling asleep, I am reconfirming that I don’t sleep enough at night, and I need to change my sleep habits. By missing the end of the show my subconscious is suggesting that most television is not worth watching and that my time would be better invested in sleeping. I fall asleep and miss the end of the show, waking up with a sore neck, a hazy sense of reality, and a lost hour or so. It takes a little while to get one’s bearings when coming up out of the black hole of sleep. So I miss the end of the show, no problem, it won’t be a rerun for me in three months when I see it again.

Category Archives: television

On missing the end of the show (because I fell asleep)

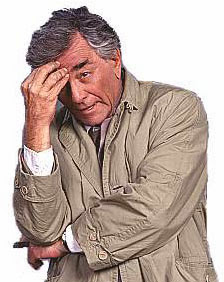

On Columbo

Like most people, I was always sucked in by Columbo. His sense of justice was fairly absolute, and he would stick to the killer until he had it figured out. The show was not a whodunnit, but it did show how Columbo would put the pieces of the puzzle together. The killers were always so mundane, killing for all of the most superficial of reasons–money, love, jealousy, fame–so predictable. His secret weapon is not that he feigns stupidity, but that he lets his personal humility run his investigations, letting his egotistical suspects hang themselves by lying when he asked them questions. He solved most of the crimes by simply letting his suspects talk. In Spain we say that it is easier to catch a liar than a one-legged man. Perhaps Columbo was successful because he was tenacious, hard-working, thoughtful, and creative–he had to be able to think like a murderer. I often wondered that if he were real, how would all of that violence and murders affect his personal life. He didn’t have time for big shots or people who thought they were better than others. He rejected the lives of the rich and famous while taking great pleasure in a simple bowl of chili. He loved his wife, took care of his dog, and drove an old Peugeot. He never dabbled in the materialistic world of his suspects, perhaps because he understood the trap of uncontrolled materialism so well. By not desiring more than he ever had and taking pleasure in life’s simple things, he had enough perspective to understand why people fail so miserably at life and kill others. That he smoked those miserable cigars and annoyed people with his incessant questions is irrelevant, part of the “smoke” screen that would put his prey at ease, allowing him to work out the complex solutions for which he was so well-known.

On Columbo

Like most people, I was always sucked in by Columbo. His sense of justice was fairly absolute, and he would stick to the killer until he had it figured out. The show was not a whodunnit, but it did show how Columbo would put the pieces of the puzzle together. The killers were always so mundane, killing for all of the most superficial of reasons–money, love, jealousy, fame–so predictable. His secret weapon is not that he feigns stupidity, but that he lets his personal humility run his investigations, letting his egotistical suspects hang themselves by lying when he asked them questions. He solved most of the crimes by simply letting his suspects talk. In Spain we say that it is easier to catch a liar than a one-legged man. Perhaps Columbo was successful because he was tenacious, hard-working, thoughtful, and creative–he had to be able to think like a murderer. I often wondered that if he were real, how would all of that violence and murders affect his personal life. He didn’t have time for big shots or people who thought they were better than others. He rejected the lives of the rich and famous while taking great pleasure in a simple bowl of chili. He loved his wife, took care of his dog, and drove an old Peugeot. He never dabbled in the materialistic world of his suspects, perhaps because he understood the trap of uncontrolled materialism so well. By not desiring more than he ever had and taking pleasure in life’s simple things, he had enough perspective to understand why people fail so miserably at life and kill others. That he smoked those miserable cigars and annoyed people with his incessant questions is irrelevant, part of the “smoke” screen that would put his prey at ease, allowing him to work out the complex solutions for which he was so well-known.

On the Grinch

Many years later, while drinking coffee with me in Starbucks, Max sleeping quietly at our feet, the Grinch told me of the day that his heart grew bigger by five sizes. He liked having a name like Cher or Madonna, but it was hard as a youngster because he scared everyone. Though he smiles a lot now, back in the day when he stilled lived in his cave, he suffered from depression and was a prisoner to much darker thoughts than he cared to discuss. Living alone, he said, was a terrible thing and no one should live in complete isolation, especially during the holidays when his solitary ways seemed so much more bitter and lonely than they did the rest of the year. He and Max moved into Whoville that year, after the “incident,” and he took a job fixing musical instruments. After his story broke, though, and the television show came out, he only did the job so he could interact with others. Secretly, he was thrilled that Boris Karloff did his voice. What the cartoon did not really go into was the depth of his depression, the breadth of his isolation, or the blackness of his despair. Up to that point Christmas and its joy had been torture. In those bad old days, he had wept openly in bitter despair upon hearing the music come up the valley to his cave. He was supposed to be happy, but he wasn’t, and he couldn’t figure out why. He sipped his triple-caramel large macchiato (with a triple shot of espresso) and got whipped cream on his lip. He laughed and smiled. Max stirred under the table. He told me about his therapy, his anti-social behavior, and his eventual road to recovery–Dr. Geisel is a genius, he said. His book about depression, and the black hole of despair to which it drove him, will be out in the spring. He is the current mayor of Whoville and hasn’t been back to the cave in years.

Many years later, while drinking coffee with me in Starbucks, Max sleeping quietly at our feet, the Grinch told me of the day that his heart grew bigger by five sizes. He liked having a name like Cher or Madonna, but it was hard as a youngster because he scared everyone. Though he smiles a lot now, back in the day when he stilled lived in his cave, he suffered from depression and was a prisoner to much darker thoughts than he cared to discuss. Living alone, he said, was a terrible thing and no one should live in complete isolation, especially during the holidays when his solitary ways seemed so much more bitter and lonely than they did the rest of the year. He and Max moved into Whoville that year, after the “incident,” and he took a job fixing musical instruments. After his story broke, though, and the television show came out, he only did the job so he could interact with others. Secretly, he was thrilled that Boris Karloff did his voice. What the cartoon did not really go into was the depth of his depression, the breadth of his isolation, or the blackness of his despair. Up to that point Christmas and its joy had been torture. In those bad old days, he had wept openly in bitter despair upon hearing the music come up the valley to his cave. He was supposed to be happy, but he wasn’t, and he couldn’t figure out why. He sipped his triple-caramel large macchiato (with a triple shot of espresso) and got whipped cream on his lip. He laughed and smiled. Max stirred under the table. He told me about his therapy, his anti-social behavior, and his eventual road to recovery–Dr. Geisel is a genius, he said. His book about depression, and the black hole of despair to which it drove him, will be out in the spring. He is the current mayor of Whoville and hasn’t been back to the cave in years.

On the Grinch

Many years later, while drinking coffee with me in Starbucks, Max sleeping quietly at our feet, the Grinch told me of the day that his heart grew bigger by five sizes. He liked having a name like Cher or Madonna, but it was hard as a youngster because he scared everyone. Though he smiles a lot now, back in the day when he stilled lived in his cave, he suffered from depression and was a prisoner to much darker thoughts than he cared to discuss. Living alone, he said, was a terrible thing and no one should live in complete isolation, especially during the holidays when his solitary ways seemed so much more bitter and lonely than they did the rest of the year. He and Max moved into Whoville that year, after the “incident,” and he took a job fixing musical instruments. After his story broke, though, and the television show came out, he only did the job so he could interact with others. Secretly, he was thrilled that Boris Karloff did his voice. What the cartoon did not really go into was the depth of his depression, the breadth of his isolation, or the blackness of his despair. Up to that point Christmas and its joy had been torture. In those bad old days, he had wept openly in bitter despair upon hearing the music come up the valley to his cave. He was supposed to be happy, but he wasn’t, and he couldn’t figure out why. He sipped his triple-caramel large macchiato (with a triple shot of espresso) and got whipped cream on his lip. He laughed and smiled. Max stirred under the table. He told me about his therapy, his anti-social behavior, and his eventual road to recovery–Dr. Geisel is a genius, he said. His book about depression, and the black hole of despair to which it drove him, will be out in the spring. He is the current mayor of Whoville and hasn’t been back to the cave in years.

Many years later, while drinking coffee with me in Starbucks, Max sleeping quietly at our feet, the Grinch told me of the day that his heart grew bigger by five sizes. He liked having a name like Cher or Madonna, but it was hard as a youngster because he scared everyone. Though he smiles a lot now, back in the day when he stilled lived in his cave, he suffered from depression and was a prisoner to much darker thoughts than he cared to discuss. Living alone, he said, was a terrible thing and no one should live in complete isolation, especially during the holidays when his solitary ways seemed so much more bitter and lonely than they did the rest of the year. He and Max moved into Whoville that year, after the “incident,” and he took a job fixing musical instruments. After his story broke, though, and the television show came out, he only did the job so he could interact with others. Secretly, he was thrilled that Boris Karloff did his voice. What the cartoon did not really go into was the depth of his depression, the breadth of his isolation, or the blackness of his despair. Up to that point Christmas and its joy had been torture. In those bad old days, he had wept openly in bitter despair upon hearing the music come up the valley to his cave. He was supposed to be happy, but he wasn’t, and he couldn’t figure out why. He sipped his triple-caramel large macchiato (with a triple shot of espresso) and got whipped cream on his lip. He laughed and smiled. Max stirred under the table. He told me about his therapy, his anti-social behavior, and his eventual road to recovery–Dr. Geisel is a genius, he said. His book about depression, and the black hole of despair to which it drove him, will be out in the spring. He is the current mayor of Whoville and hasn’t been back to the cave in years.

On waiting

Waiting is a very odd experience that is filled with both anticipation and frustration. Waiting in line is the ultimate human frustration because one never knows if one’s petition will be fulfilled or if one will be sent to the end of the line, again. Waiting in line at the grocery store to check out and pay doesn’t seem to bother most people, but if I only have a handful of items, why is the person ahead of me trying to go through the express line with an entire cartload of items? Getting in and getting out of the grocery store in a timely fashion is almost impossible because no one wants to wait. Waiting in line at the airport to do almost anything–check in, get re-booked, get on the plane, get off the plane–is a complete fiasco given the complexity of the tasks at hand, especially trying to get re-booked after a cancellation or delay or missed flight. Yet, waiting with anticipation for a package to arrive is an interesting state of mind, giddy almost. Waiting for the weekend can be both exciting and frustrating, especially if you are standing in line to get re-booked because your flight was canceled. Some people have an enormous capacity for waiting, or they have given up hope and are resigned to their fate in life–to wait eternally. Others are waiting for the end of times, which they see right around the corner, but of course, they are still waiting. Personally, I hate waiting at stop lights especially when I am the only car at the intersection and it’s 2 a.m. Waiting for the commercials to end and the television program to begin again is like waiting for Godot, and when the program comes back on I have frequently forgotten what it was that I was watching in the first place. Waiting for the bread to bake or the cookies to come out of the oven is definitely worth it–they taste that much better. Waiting for the bus on a cold winter’s day is no fun no matter how you slice it. Waiting for your date to show up and you are all alone and the whole world knows it is an empty feeling which needs no explanation. Do you wait for the mail with anticipation or dread. Can you wait to collect your first social security check. I’ll probably get my first one while I’m waiting at an empty stoplight in the middle of the night somewhere. Apparently, waiting in line at large amusement parks is not fun, and if you have no morals or scruples, you can cut the line. Waiting in a traffic jam, especially when you are late already, is liable to cause a complete breakdown. If you are waiting for someone to call you back about a job, stop waiting because they aren’t calling. I have a personal loathing for waiting rooms, especially if it is a doctor’s waiting room. I think we should be able to bill doctors if we have to wait more than fifteen minutes after our scheduled appointment time. Waiting to get your car back from the shop is nightmarish. Some people wait all alone in the dark, as Billy Joel once sang. I suppose heaven can wait. I am not a patient man, do not bear fool’s lightly, and I hate to wait especially when I’m not the problem. Yet, there are those people who wait patiently, smile, bear up, stay in good humor, and kindly wait until it is there turn. This is either an enormous virtue or a miracle, but I can’t decide which.

On waiting

Waiting is a very odd experience that is filled with both anticipation and frustration. Waiting in line is the ultimate human frustration because one never knows if one’s petition will be fulfilled or if one will be sent to the end of the line, again. Waiting in line at the grocery store to check out and pay doesn’t seem to bother most people, but if I only have a handful of items, why is the person ahead of me trying to go through the express line with an entire cartload of items? Getting in and getting out of the grocery store in a timely fashion is almost impossible because no one wants to wait. Waiting in line at the airport to do almost anything–check in, get re-booked, get on the plane, get off the plane–is a complete fiasco given the complexity of the tasks at hand, especially trying to get re-booked after a cancellation or delay or missed flight. Yet, waiting with anticipation for a package to arrive is an interesting state of mind, giddy almost. Waiting for the weekend can be both exciting and frustrating, especially if you are standing in line to get re-booked because your flight was canceled. Some people have an enormous capacity for waiting, or they have given up hope and are resigned to their fate in life–to wait eternally. Others are waiting for the end of times, which they see right around the corner, but of course, they are still waiting. Personally, I hate waiting at stop lights especially when I am the only car at the intersection and it’s 2 a.m. Waiting for the commercials to end and the television program to begin again is like waiting for Godot, and when the program comes back on I have frequently forgotten what it was that I was watching in the first place. Waiting for the bread to bake or the cookies to come out of the oven is definitely worth it–they taste that much better. Waiting for the bus on a cold winter’s day is no fun no matter how you slice it. Waiting for your date to show up and you are all alone and the whole world knows it is an empty feeling which needs no explanation. Do you wait for the mail with anticipation or dread. Can you wait to collect your first social security check. I’ll probably get my first one while I’m waiting at an empty stoplight in the middle of the night somewhere. Apparently, waiting in line at large amusement parks is not fun, and if you have no morals or scruples, you can cut the line. Waiting in a traffic jam, especially when you are late already, is liable to cause a complete breakdown. If you are waiting for someone to call you back about a job, stop waiting because they aren’t calling. I have a personal loathing for waiting rooms, especially if it is a doctor’s waiting room. I think we should be able to bill doctors if we have to wait more than fifteen minutes after our scheduled appointment time. Waiting to get your car back from the shop is nightmarish. Some people wait all alone in the dark, as Billy Joel once sang. I suppose heaven can wait. I am not a patient man, do not bear fool’s lightly, and I hate to wait especially when I’m not the problem. Yet, there are those people who wait patiently, smile, bear up, stay in good humor, and kindly wait until it is there turn. This is either an enormous virtue or a miracle, but I can’t decide which.

On soap operas

The first soaps I remember as a small child were “As the World Turns” and “The Edge of Night,” which were the daytime dramas which my mother watched from time to time while taking care of two children under the age of five. I can’t say that at that age I understood anything that I saw on the screen, but I did get the impression, often, that most of these soap opera people were troubled, in trouble, or just plain trouble. What completely escaped me was both the meaning and purpose of these never ending dramas that ended each day with a small (or big) cliffhanger. Yet, in spite of the accidents, murders, and kidnappings, all or most of the characters just kept limping along from episode to episode. One older woman seemed to have been married to every male character on the show at one point or another. Children that were infants in March were going to school in September. My mother dismissed these inconsistencies by saying “Oh, these are just my stories,” as if this explained all the weird shenanigans on the soaps. Perhaps the great appeal of these television shows lies precisely in the magical fact that they never ended and all the viewers knew this. No matter how bad it ever got–fires, earthquakes, shootings, disappearances, mistaken identities, vampires and werewolves–the show, with all its characters, would be there again tomorrow–same time, same station, same evil doers, same matriarchs, same torment souls–and the day after and the day after. So no matter the strange vicissitudes of the characters, everything would continue on just about the same from day to day. The acting was melodramatic, the stories were predictable, the sets were made of cardboard, and the dialogues were shamefully the same. In fact, I think that most of the viewers were frequently hoping for a cataclysmic flood or fire, an earthquake, a bank robbery, a mistaken identity, a new wedding, a new baby, an unexpected pregnancy, or the disappearance of a major character. As a very young child, I was confused by the serious attitude of the characters and often wondered if it was difficult for the actors to keep a straight face and actually do the dialogues as written. For the most part, the women were elegant and the men, handsome, unless they were evil, in which case they were often represented as ugly miscreants who did not fit it with the utopian society of the television serial. There homes were nice, their jobs, good ones. Yet they suffered infidelities ad nauseum, and at some point or other every single character had been in bed with every single other character of the opposite sex–there wasn’t even the slightest whiff same-sex relationships, or maybe I was just too young to know. Later, when I would have to stay home because I was sick, or it was summer and I was home, tuning into these shows only proved that nothing ever really happened, that the results of an atomic explosion on a soap opera don’t really have any consequences in the long run–perhaps Aunt Hortensia, who has been lost for thirty years, (probably living in Europe), comes back from the dead to move in with a daughter who hates here. The plot possibilities and twists are endless within the format because the viewers expect repetition, not verisimilitude, and they want everything to be the same year in and year out–heroes, villains, were often one and the same person. They want to see the same faces year in and year out, and so some of the most venerated actors in a soap are the ones who last thirty years, get married fourteen times, and have eleven children by the age of 25. Some actors did over two hundred live shows a year during the heyday of the soap. Today, I can’t watch them because they seem goofy and overtly melodramatic, but then again, maybe I’ve just grown too old and cynical.

On soap operas

The first soaps I remember as a small child were “As the World Turns” and “The Edge of Night,” which were the daytime dramas which my mother watched from time to time while taking care of two children under the age of five. I can’t say that at that age I understood anything that I saw on the screen, but I did get the impression, often, that most of these soap opera people were troubled, in trouble, or just plain trouble. What completely escaped me was both the meaning and purpose of these never ending dramas that ended each day with a small (or big) cliffhanger. Yet, in spite of the accidents, murders, and kidnappings, all or most of the characters just kept limping along from episode to episode. One older woman seemed to have been married to every male character on the show at one point or another. Children that were infants in March were going to school in September. My mother dismissed these inconsistencies by saying “Oh, these are just my stories,” as if this explained all the weird shenanigans on the soaps. Perhaps the great appeal of these television shows lies precisely in the magical fact that they never ended and all the viewers knew this. No matter how bad it ever got–fires, earthquakes, shootings, disappearances, mistaken identities, vampires and werewolves–the show, with all its characters, would be there again tomorrow–same time, same station, same evil doers, same matriarchs, same torment souls–and the day after and the day after. So no matter the strange vicissitudes of the characters, everything would continue on just about the same from day to day. The acting was melodramatic, the stories were predictable, the sets were made of cardboard, and the dialogues were shamefully the same. In fact, I think that most of the viewers were frequently hoping for a cataclysmic flood or fire, an earthquake, a bank robbery, a mistaken identity, a new wedding, a new baby, an unexpected pregnancy, or the disappearance of a major character. As a very young child, I was confused by the serious attitude of the characters and often wondered if it was difficult for the actors to keep a straight face and actually do the dialogues as written. For the most part, the women were elegant and the men, handsome, unless they were evil, in which case they were often represented as ugly miscreants who did not fit it with the utopian society of the television serial. There homes were nice, their jobs, good ones. Yet they suffered infidelities ad nauseum, and at some point or other every single character had been in bed with every single other character of the opposite sex–there wasn’t even the slightest whiff same-sex relationships, or maybe I was just too young to know. Later, when I would have to stay home because I was sick, or it was summer and I was home, tuning into these shows only proved that nothing ever really happened, that the results of an atomic explosion on a soap opera don’t really have any consequences in the long run–perhaps Aunt Hortensia, who has been lost for thirty years, (probably living in Europe), comes back from the dead to move in with a daughter who hates here. The plot possibilities and twists are endless within the format because the viewers expect repetition, not verisimilitude, and they want everything to be the same year in and year out–heroes, villains, were often one and the same person. They want to see the same faces year in and year out, and so some of the most venerated actors in a soap are the ones who last thirty years, get married fourteen times, and have eleven children by the age of 25. Some actors did over two hundred live shows a year during the heyday of the soap. Today, I can’t watch them because they seem goofy and overtly melodramatic, but then again, maybe I’ve just grown too old and cynical.