Whenever I feel a bittersweet feeling of melancholy and nostalgia creep into my bones, I also start to think about all of the molded gelatin salads that I ate at innumerable potlucks held by the Lutheran ladies in the church of my youth. Although I wouldn’t blame Lutherans for inventing the molded jello salad, I would fault them for raising the recipe to high art, albeit “pop” art, populism in its most base form. Though the term “exotic” never enters the same sentence describing the nature of gelatin desserts, most cooks making a strangely shaped gelatin dessert thought they were bordering on the exotic, if not original, use of gelatin. Whenever I eat gelatin, I am always reminded of the bowls of red gelatin that came out in summer to celebrate friends, family and colleagues at picnics, reunions, and random get-togethers. I still love red gelatin, but I don’t want anything odd in it. I think there still exists a tendency on the part of some cooks to “jazz up” their recipes and presentations by adding other foods, fruit cocktail and little canned tangerines being among the most common. I have also see shrimp, tuna, cabbage, olives, anchovies, spam, celery, carrots and radishes floating suspended in green gelatin. There is something rather grotesque about seeing a shrimp suspended in green gelatin coming toward your mouth. Just because you can suspend different fruits, vegetables, meats, and fish in gelatin does not mean you should do it, necessarily. Gelatin is rather sweet, and it seems rather diabolical, if not unethical, to mix olives and Spam into a molded gelatin salad–and it’s not really salad either. I’ve seen people make some rather entertaining desserts constructed of gelatin cubes and whipped cream, but this a far cry from celery, carrots and cabbage in gelatin. I often wonder if the creators of such monstrosities ever eat their own potential fiascoes. Gelatin as a food is problematic for lots of reasons, not the least of which is its wiggly nature. Being transparent doesn’t help because unwary cooks will always fall into the trap of trying to put something interesting into the gelatin for the unwary consumer to look at. Just because you can do something does not necessarily mean you should. Gelatin cut into cubes, stacked in a decorative glass, and topped with a little whipped cream, though not very daring, is an acceptable dessert. Gelatin forced into strange molds of fish, dogs, geometric shapes, and rings is not. Is there a creepier food out there than a yellow gelatin molded fish with canned mandarin oranges and tiny salad shrimps suspended in it? And it’s been garnished with celery and parsley by some adventurous and imaginative cook who scammed the recipe out of that one church cookbook her cousin Marge gave her. Or a large five-pointed star of molded red gelatin in which someone has suspended chopped olives, fruit cocktail, and shredded carrots? Perhaps the only thing weirder than that is seeing a ring of orange gelatin with little bits of stuff floating in it which you cannot identify at all. I’ve eaten a lot of weird things, but between the slimy giggle factor and its unidentified contents, a strange molded gelatin salad is not my idea of good eats, but I say this not because I hate gelatin, but because as a food it has been abused by creative cooks anxious to impress the in-laws with some wildly exotic combination of shredded Spam and horseradish, which when suspended in gelatin in the company of white rice might be considered criminal behavior. Really, don’t make me cry. Just give me a bowl of red gelatin with nothing weird in it, and I will be a happy camper–end of story.

Whenever I feel a bittersweet feeling of melancholy and nostalgia creep into my bones, I also start to think about all of the molded gelatin salads that I ate at innumerable potlucks held by the Lutheran ladies in the church of my youth. Although I wouldn’t blame Lutherans for inventing the molded jello salad, I would fault them for raising the recipe to high art, albeit “pop” art, populism in its most base form. Though the term “exotic” never enters the same sentence describing the nature of gelatin desserts, most cooks making a strangely shaped gelatin dessert thought they were bordering on the exotic, if not original, use of gelatin. Whenever I eat gelatin, I am always reminded of the bowls of red gelatin that came out in summer to celebrate friends, family and colleagues at picnics, reunions, and random get-togethers. I still love red gelatin, but I don’t want anything odd in it. I think there still exists a tendency on the part of some cooks to “jazz up” their recipes and presentations by adding other foods, fruit cocktail and little canned tangerines being among the most common. I have also see shrimp, tuna, cabbage, olives, anchovies, spam, celery, carrots and radishes floating suspended in green gelatin. There is something rather grotesque about seeing a shrimp suspended in green gelatin coming toward your mouth. Just because you can suspend different fruits, vegetables, meats, and fish in gelatin does not mean you should do it, necessarily. Gelatin is rather sweet, and it seems rather diabolical, if not unethical, to mix olives and Spam into a molded gelatin salad–and it’s not really salad either. I’ve seen people make some rather entertaining desserts constructed of gelatin cubes and whipped cream, but this a far cry from celery, carrots and cabbage in gelatin. I often wonder if the creators of such monstrosities ever eat their own potential fiascoes. Gelatin as a food is problematic for lots of reasons, not the least of which is its wiggly nature. Being transparent doesn’t help because unwary cooks will always fall into the trap of trying to put something interesting into the gelatin for the unwary consumer to look at. Just because you can do something does not necessarily mean you should. Gelatin cut into cubes, stacked in a decorative glass, and topped with a little whipped cream, though not very daring, is an acceptable dessert. Gelatin forced into strange molds of fish, dogs, geometric shapes, and rings is not. Is there a creepier food out there than a yellow gelatin molded fish with canned mandarin oranges and tiny salad shrimps suspended in it? And it’s been garnished with celery and parsley by some adventurous and imaginative cook who scammed the recipe out of that one church cookbook her cousin Marge gave her. Or a large five-pointed star of molded red gelatin in which someone has suspended chopped olives, fruit cocktail, and shredded carrots? Perhaps the only thing weirder than that is seeing a ring of orange gelatin with little bits of stuff floating in it which you cannot identify at all. I’ve eaten a lot of weird things, but between the slimy giggle factor and its unidentified contents, a strange molded gelatin salad is not my idea of good eats, but I say this not because I hate gelatin, but because as a food it has been abused by creative cooks anxious to impress the in-laws with some wildly exotic combination of shredded Spam and horseradish, which when suspended in gelatin in the company of white rice might be considered criminal behavior. Really, don’t make me cry. Just give me a bowl of red gelatin with nothing weird in it, and I will be a happy camper–end of story.

Category Archives: shipwreck

On a molded gelatin salad

Whenever I feel a bittersweet feeling of melancholy and nostalgia creep into my bones, I also start to think about all of the molded gelatin salads that I ate at innumerable potlucks held by the Lutheran ladies in the church of my youth. Although I wouldn’t blame Lutherans for inventing the molded jello salad, I would fault them for raising the recipe to high art, albeit “pop” art, populism in its most base form. Though the term “exotic” never enters the same sentence describing the nature of gelatin desserts, most cooks making a strangely shaped gelatin dessert thought they were bordering on the exotic, if not original, use of gelatin. Whenever I eat gelatin, I am always reminded of the bowls of red gelatin that came out in summer to celebrate friends, family and colleagues at picnics, reunions, and random get-togethers. I still love red gelatin, but I don’t want anything odd in it. I think there still exists a tendency on the part of some cooks to “jazz up” their recipes and presentations by adding other foods, fruit cocktail and little canned tangerines being among the most common. I have also see shrimp, tuna, cabbage, olives, anchovies, spam, celery, carrots and radishes floating suspended in green gelatin. There is something rather grotesque about seeing a shrimp suspended in green gelatin coming toward your mouth. Just because you can suspend different fruits, vegetables, meats, and fish in gelatin does not mean you should do it, necessarily. Gelatin is rather sweet, and it seems rather diabolical, if not unethical, to mix olives and Spam into a molded gelatin salad–and it’s not really salad either. I’ve seen people make some rather entertaining desserts constructed of gelatin cubes and whipped cream, but this a far cry from celery, carrots and cabbage in gelatin. I often wonder if the creators of such monstrosities ever eat their own potential fiascoes. Gelatin as a food is problematic for lots of reasons, not the least of which is its wiggly nature. Being transparent doesn’t help because unwary cooks will always fall into the trap of trying to put something interesting into the gelatin for the unwary consumer to look at. Just because you can do something does not necessarily mean you should. Gelatin cut into cubes, stacked in a decorative glass, and topped with a little whipped cream, though not very daring, is an acceptable dessert. Gelatin forced into strange molds of fish, dogs, geometric shapes, and rings is not. Is there a creepier food out there than a yellow gelatin molded fish with canned mandarin oranges and tiny salad shrimps suspended in it? And it’s been garnished with celery and parsley by some adventurous and imaginative cook who scammed the recipe out of that one church cookbook her cousin Marge gave her. Or a large five-pointed star of molded red gelatin in which someone has suspended chopped olives, fruit cocktail, and shredded carrots? Perhaps the only thing weirder than that is seeing a ring of orange gelatin with little bits of stuff floating in it which you cannot identify at all. I’ve eaten a lot of weird things, but between the slimy giggle factor and its unidentified contents, a strange molded gelatin salad is not my idea of good eats, but I say this not because I hate gelatin, but because as a food it has been abused by creative cooks anxious to impress the in-laws with some wildly exotic combination of shredded Spam and horseradish, which when suspended in gelatin in the company of white rice might be considered criminal behavior. Really, don’t make me cry. Just give me a bowl of red gelatin with nothing weird in it, and I will be a happy camper–end of story.

Whenever I feel a bittersweet feeling of melancholy and nostalgia creep into my bones, I also start to think about all of the molded gelatin salads that I ate at innumerable potlucks held by the Lutheran ladies in the church of my youth. Although I wouldn’t blame Lutherans for inventing the molded jello salad, I would fault them for raising the recipe to high art, albeit “pop” art, populism in its most base form. Though the term “exotic” never enters the same sentence describing the nature of gelatin desserts, most cooks making a strangely shaped gelatin dessert thought they were bordering on the exotic, if not original, use of gelatin. Whenever I eat gelatin, I am always reminded of the bowls of red gelatin that came out in summer to celebrate friends, family and colleagues at picnics, reunions, and random get-togethers. I still love red gelatin, but I don’t want anything odd in it. I think there still exists a tendency on the part of some cooks to “jazz up” their recipes and presentations by adding other foods, fruit cocktail and little canned tangerines being among the most common. I have also see shrimp, tuna, cabbage, olives, anchovies, spam, celery, carrots and radishes floating suspended in green gelatin. There is something rather grotesque about seeing a shrimp suspended in green gelatin coming toward your mouth. Just because you can suspend different fruits, vegetables, meats, and fish in gelatin does not mean you should do it, necessarily. Gelatin is rather sweet, and it seems rather diabolical, if not unethical, to mix olives and Spam into a molded gelatin salad–and it’s not really salad either. I’ve seen people make some rather entertaining desserts constructed of gelatin cubes and whipped cream, but this a far cry from celery, carrots and cabbage in gelatin. I often wonder if the creators of such monstrosities ever eat their own potential fiascoes. Gelatin as a food is problematic for lots of reasons, not the least of which is its wiggly nature. Being transparent doesn’t help because unwary cooks will always fall into the trap of trying to put something interesting into the gelatin for the unwary consumer to look at. Just because you can do something does not necessarily mean you should. Gelatin cut into cubes, stacked in a decorative glass, and topped with a little whipped cream, though not very daring, is an acceptable dessert. Gelatin forced into strange molds of fish, dogs, geometric shapes, and rings is not. Is there a creepier food out there than a yellow gelatin molded fish with canned mandarin oranges and tiny salad shrimps suspended in it? And it’s been garnished with celery and parsley by some adventurous and imaginative cook who scammed the recipe out of that one church cookbook her cousin Marge gave her. Or a large five-pointed star of molded red gelatin in which someone has suspended chopped olives, fruit cocktail, and shredded carrots? Perhaps the only thing weirder than that is seeing a ring of orange gelatin with little bits of stuff floating in it which you cannot identify at all. I’ve eaten a lot of weird things, but between the slimy giggle factor and its unidentified contents, a strange molded gelatin salad is not my idea of good eats, but I say this not because I hate gelatin, but because as a food it has been abused by creative cooks anxious to impress the in-laws with some wildly exotic combination of shredded Spam and horseradish, which when suspended in gelatin in the company of white rice might be considered criminal behavior. Really, don’t make me cry. Just give me a bowl of red gelatin with nothing weird in it, and I will be a happy camper–end of story.

On Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe, just as fictional a character as Don Quixote or Sherlock Holmes, has come to be just as real as Ishmael or Harry Potter. Shipwrecked and alone on a Caribbean island, Crusoe must rebuild his solitary life as an Englishman, lost in a wilderness and with no hope of rescue in the near future. The idea of living for years, abandoned and alone on an island far from civilization, is a frightening one. Most people cannot even begin to imagine what it might be like to live in isolation from all human contact. Of course, there are those who might dream of such an arrangement, but for the most part, we are gregarious and need human interaction to be happy and productive. Human interaction gives meaning and purpose to our lives. Being a “castaway” with no hope of rescue is almost as horrifying as being walled up behind a brick wall. Our literature is filled with these surreal situations which firmly address some of the deepest and darkest human fears, one of which being the fate of Robinson Crusoe: to find oneself totally alone with no hope of relief in the near future. The very term, “castaway,” seems to devalue the victim of an accident over which they may have had no control, such as shipwreck. To be a castaway is to find oneself alone and abandoned, deprived of the creature comforts, deprived of human interaction, deprived of the structures that give our lives meaning–law, commerce, culture, society, ethics, art, time, neighbors, family. The enormous challenge that the character must face is his own motivation for taking care of himself in the face of having to live absolutely alone forever. The idea of rescue is probably the only thing that stands between Crusoe and his own insanity. In other words, the hope of rescue, no matter how small, is that one little glimmer of hope that keeps the castaway from just lying down and dying where he has washed up on the shore of his desert island. What is curious about the novel and Crusoe is how he is faced with reinventing a series of technologies that he has always taken for granted: the wheel, a shovel, baskets, bottles, cooking dishes, barrels. Eventually, he will adapt what he has on the island to solve many of these sorts of problems, but he is very vexed at recreating a table and chair for himself, realizing that the skilled craftsman who create these common everyday items are very highly skilled and armed with the highly specialized tools of their trades. Alone with only a minimum of tools and raw materials, Crusoe must come to terms with his own inadequacy as a craftsman with no training and no skills. Crusoe cannot reinvent England on his island, although he tries very hard. When he is sick, he has no doctor, when he wants to make bread, he has no flour, when he needs advice, he is alone. He lives, eats, sleeps, hunts, works, and walks absolutely by himself. When the tide rises, the storms rise up, the earth shakes, the sun beats down, he must face all of these things alone. Crusoe’s levels of desperation are real and frequently bring him to tears, but the power of self-preservation is so strong and so persistent that in spite of an overwhelming sense of hopelessness, he still gets up every day and stays alive, working, eating, cleaning, planning, inventing, solving problems. Crusoe’s story is credible, verging on verisimilitude, in fact because the human spirit, even in the face of horrific odds, is indomitable and unbending, invincible as it were. Crusoe has lots of failures as he attempts to rebuild English society on his little island, but he also has many successes, growing grain, training a parrot, building his “homes.” In the end, of course, he does leave his island with his man, Friday, but he has spent almost three decades on his desert island jail.

On losing

Perhaps there is no better lesson in life than learning to lose well. Those that say winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing, are doomed to a life of frustration and despair. Some win and others lose, but in the end, most lose. In all the major professional sports, all except the one winning team end their seasons with a loss or have a losing record. Learning to lose well and be a good sport about it is even more important in real life situations where you don’t get the job, a project falls through, you get laid off, you just don’t get picked, the promotion train leaves you behind, she/he picks someone else and leaves you alone. Life, especially in politics where winning and losing define us as a nation, is mostly about losing and seldom about winning. For most of my life I’ve had to deal with losing most or all of the elections in which I’ve had any interest at all, and sometimes not particularly thrilled about the ones I’ve won. Winning is illusory and fleeting because all people remember is the last five minutes, not the last five years. History is full of losing causes, but you seldom see them because the winners write the stories. Losing is a day-to-day fact that has to be sucked up and dealt with. There are lots of sad and angry people around America tonight because they think their loss was unjust or unwarranted or just plain wrong. Yet I would also suggest that if their candidate lost tonight, that it will mean little or nothing tomorrow. You see, that’s the secret about losing in politics: there is always another election in two years, or four years, or six years. Nothing in life is forever, not even taxes. Look at Richard Nixon, he was a big-time loser in 1960 who went on to score a couple of sweet conservative victories before he publicly disgraced himself with Watergate. Gerald Ford, the man who pardoned him and assumed the office of the presidency had to live with the bitter notion that he was never elected to be the president of the United States—he had to be appointed. Nixon, in his second election against George McGovern, a man who really knew how to lose, Nixon took 49 of 50 states. McGovern didn’t even take his home state. I’m not about to say that losing builds character because that ‘s not true, but losing might temper your character, and you might develop such mental health factors such as empathy, kindness, generosity, self-awareness, tolerance. If the only thing you can see in tonight’s loss is your own bruised ego, then you have a little soul-searching to do because this loss is nothing compared to what life has in store for you. And you won’t like it, and it will be much worse than any political whipping you might endure. Life is not about winning anything, but it is about enduring loss and losing because that’s all we have some days, so we better know how to handle it when the clouds turn black and you find yourself in the midst of a dark night, off of the path, lost in a dark and savage wood. Grace in the face of a loss never goes unnoticed or unappreciated. Funny how life works that way.

On losing

Perhaps there is no better lesson in life than learning to lose well. Those that say winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing, are doomed to a life of frustration and despair. Some win and others lose, but in the end, most lose. In all the major professional sports, all except the one winning team end their seasons with a loss or have a losing record. Learning to lose well and be a good sport about it is even more important in real life situations where you don’t get the job, a project falls through, you get laid off, you just don’t get picked, the promotion train leaves you behind, she/he picks someone else and leaves you alone. Life, especially in politics where winning and losing define us as a nation, is mostly about losing and seldom about winning. For most of my life I’ve had to deal with losing most or all of the elections in which I’ve had any interest at all, and sometimes not particularly thrilled about the ones I’ve won. Winning is illusory and fleeting because all people remember is the last five minutes, not the last five years. History is full of losing causes, but you seldom see them because the winners write the stories. Losing is a day-to-day fact that has to be sucked up and dealt with. There are lots of sad and angry people around America tonight because they think their loss was unjust or unwarranted or just plain wrong. Yet I would also suggest that if their candidate lost tonight, that it will mean little or nothing tomorrow. You see, that’s the secret about losing in politics: there is always another election in two years, or four years, or six years. Nothing in life is forever, not even taxes. Look at Richard Nixon, he was a big-time loser in 1960 who went on to score a couple of sweet conservative victories before he publicly disgraced himself with Watergate. Gerald Ford, the man who pardoned him and assumed the office of the presidency had to live with the bitter notion that he was never elected to be the president of the United States—he had to be appointed. Nixon, in his second election against George McGovern, a man who really knew how to lose, Nixon took 49 of 50 states. McGovern didn’t even take his home state. I’m not about to say that losing builds character because that ‘s not true, but losing might temper your character, and you might develop such mental health factors such as empathy, kindness, generosity, self-awareness, tolerance. If the only thing you can see in tonight’s loss is your own bruised ego, then you have a little soul-searching to do because this loss is nothing compared to what life has in store for you. And you won’t like it, and it will be much worse than any political whipping you might endure. Life is not about winning anything, but it is about enduring loss and losing because that’s all we have some days, so we better know how to handle it when the clouds turn black and you find yourself in the midst of a dark night, off of the path, lost in a dark and savage wood. Grace in the face of a loss never goes unnoticed or unappreciated. Funny how life works that way.

On bifurcating paths

How do we end up where we are? The other day a visiting student asked why I became a college professor, and I was at a loss for words. The bifurcating paths of my own life seem chaotic, capricious, and strange. How does one pick a major? Deciding a path of studies is simple for many, but how did a boy from the prairie of southern Minnesota decide to study a language to which he has no ties, neither genetic nor tradition? I had no family in Spain. None of my family had ever been a Spanish teacher or a professor of literature. My people are farmers who tilled the ground, raised chickens and pigs, milked cowes, bailed hay, and picked corn. Nobody had ever conjugated a verb in Spanish, no one had ever read the Cid or Don Quixote, no one had ever worked in a university, written a scholarly paper, or published a book. So an economics professor who didn’t know me put me in a Spanish class when I was a freshmen, but only because I had already studied Spanish for five years in junior high and high school. I had done that because my mother and the Spanish teacher were best friends who had met in the League of Women Voters. So what happens if the Spanish teacher’s husband doesn’t get a job in the local college that brings him (and his Spanish teaching wife) to my home town? What would have happened if I hadn’t had a politically active mother who was interested in social justice for women? Where do the bifurcating paths begin? Does it matter that my father had a terrible job in another town that motivated him to search for better work in the town where I grew up? The paths have been splitting over and over again for decades and continue to split even as I write this. So I majored in Spanish at an American-Lutheran-Swedish school whose specialty was really pre-med majors and Lutheran pastors. After I graduated I couldn’t get a decent job, but I was motivated to go back to school by a random comment by a favorite History professor–“What about Middlebury?” he said. After I graduated from Middlebury I decided I wanted to live in Europe for awhile, so I did that. Six years earlier, in 1980, walking past a bulletin board at St. Louis University in Madrid I saw an advertisement for the graduate program in Spanish at the University of Minnesota. I applied in 1985, they loved me, I loved them, and I graduated with my PhD in medieval Spanish literature in 1993. The combination of happenstance, historical caprice (Franco was dead), luck, coincidence, serendipitous causalities, and unnatural timing have carried me through the vortex of the space-time continuum to this place called Waco. If the dominoes had not fallen in a very specific way, I might be someone completely different, but even knowing that, I wouldn’t change anything, and I say that as if I had any control over any of that chain of choices and happenings. I am the most unlikely person doing a most unlikely job given my history, family and circumstances. How does this happen?

On bifurcating paths

How do we end up where we are? The other day a visiting student asked why I became a college professor, and I was at a loss for words. The bifurcating paths of my own life seem chaotic, capricious, and strange. How does one pick a major? Deciding a path of studies is simple for many, but how did a boy from the prairie of southern Minnesota decide to study a language to which he no ties, neither genetic nor tradition? I had no family in Spain. None of my family had ever been a Spanish teacher or a professor of literature. My people are farmers who tilled the ground, raised chickens and pigs, milked cowes, bailed hay, and picked corn. Nobody had ever conjugated a verb in Spanish, no one had ever read the Cid or Don Quixote, no one had ever worked in a university, written a scholarly paper, or published a book. So an economics professor who didn’t know me put me in a Spanish class when I was a freshmen, but only because I had already studied Spanish for five years in junior high and high school. I had done that because my mother and the Spanish teacher were best friends who had met in the League of Women Voters. So what happens if the Spanish teacher’s husband doesn’t get a job in the local college that brings him (and his Spanish teaching wife) to my home town? What would have happened if I hadn’t had a politically active mother who was interested in social justice for women? Where do the bifurcating paths begin? Does it matter that my father had a terrible job in another town that motivated him to search for better work in the town where I grew up? The paths have been splitting over and over again for decades and continue to split even as I write this. So I majored in Spanish at an American-Lutheran-Swedish school whose specialty was really pre-med majors and Lutheran pastors. After I graduated I couldn’t get a decent job, but I was motivated to go back to school by a random comment by a favorite History professor–“What about Middlebury?” he said. After I graduated from Middlebury I decided I wanted to live in Europe for awhile, so I did that. Six years earlier, in 1980, walking past a bulletin board at St. Louis University in Madrid I saw an advertisement for the graduate program in Spanish at the University of Minnesota. I applied in 1985, they loved me, I loved them, and I graduated with my PhD in medieval Spanish literature in 1993. The combination of happenstance, historical caprice (Franco was dead), luck, coincidence, serendipitous causalities, and unnatural timing have carried me through the vortex of the space-time continuum to this place called Waco. If the dominoes had not fallen in a very specific way, I might be someone completely different, but even knowing that, I wouldn’t change anything, and I say that as if I had any control over any of that chain of choices and happenings. I am the most unlikely person doing a most unlikely job given my history, family and circumstances. How does this happen?

On diaspora

Though I have lived far from home, spoken a language I had to learn, eaten strange food, missed my family, I have never been forced to leave my homeland never to return, yet for many people, it has happened more than once, and it continues to be the their “pan de cada día” or their everyday experience. Diaspora is about the scattering of a people, a forced exile, a leaving behind, a tragedy, a disaster. Diaspora has many causes–wars, revolutions, racial cleansing, religious unity, human cruelty, the settling of old scores, scapegoating–but any is as good as none at all if you don’t need one. The cruelty of the diaspora experience is not necessarily about change, but about loss–of tradition, of customs, of language, of an enduring mental landscape that has been left behind. The cruelty of nostalgia resides in the persistence of memory, of families, of lives, of art, of songs, of celebrations. Diaspora is about a separation from what is comfortable, what is expected, happiness, joy, friends, births, weddings, deaths. As a group of people fan out to find new homes, they meet the challenge of finding all the rest of the world already occupied, and if they have been forced to leave one place, they will probably be less than welcome wherever they go. Those who suffer diaspora, forced to leave their homes again and again, will eventually become errant and drifting, unwilling to call anywhere home. Eventually, after being rejected enough, you have an entire group of people with nothing to lose, wandering the world in search of a home. All people want a place to call their home. This is a basic human desire, to have a family and a job and a roof over our heads and not have to move every few years. Diaspora breaks up families, history and tradition are forgotten, identity becomes variable, languages are both forgotten and learned, The dead are left behind, forgotten in unattended graves. Possessions, the relics of tradition, must be packed and transported or left behind. Wealth and land are left behind, lost forever. Perhaps new beginnings in new places can be a good thing as it has been for immigrants around the world, but the nostalgia for what has been lost is an ethos that has come to be emblematic of the human condition. In many ways, diaspora is the human condition.

Though I have lived far from home, spoken a language I had to learn, eaten strange food, missed my family, I have never been forced to leave my homeland never to return, yet for many people, it has happened more than once, and it continues to be the their “pan de cada día” or their everyday experience. Diaspora is about the scattering of a people, a forced exile, a leaving behind, a tragedy, a disaster. Diaspora has many causes–wars, revolutions, racial cleansing, religious unity, human cruelty, the settling of old scores, scapegoating–but any is as good as none at all if you don’t need one. The cruelty of the diaspora experience is not necessarily about change, but about loss–of tradition, of customs, of language, of an enduring mental landscape that has been left behind. The cruelty of nostalgia resides in the persistence of memory, of families, of lives, of art, of songs, of celebrations. Diaspora is about a separation from what is comfortable, what is expected, happiness, joy, friends, births, weddings, deaths. As a group of people fan out to find new homes, they meet the challenge of finding all the rest of the world already occupied, and if they have been forced to leave one place, they will probably be less than welcome wherever they go. Those who suffer diaspora, forced to leave their homes again and again, will eventually become errant and drifting, unwilling to call anywhere home. Eventually, after being rejected enough, you have an entire group of people with nothing to lose, wandering the world in search of a home. All people want a place to call their home. This is a basic human desire, to have a family and a job and a roof over our heads and not have to move every few years. Diaspora breaks up families, history and tradition are forgotten, identity becomes variable, languages are both forgotten and learned, The dead are left behind, forgotten in unattended graves. Possessions, the relics of tradition, must be packed and transported or left behind. Wealth and land are left behind, lost forever. Perhaps new beginnings in new places can be a good thing as it has been for immigrants around the world, but the nostalgia for what has been lost is an ethos that has come to be emblematic of the human condition. In many ways, diaspora is the human condition.

On diaspora

Though I have lived far from home, spoken a language I had to learn, eaten strange food, missed my family, I have never been forced to leave my homeland never to return, yet for many people, it has happened more than once, and it continues to be the their “pan de cada día” or their everyday experience. Diaspora is about the scattering of a people, a forced exile, a leaving behind, a tragedy, a disaster. Diaspora has many causes–wars, revolutions, racial cleansing, religious unity, human cruelty, the settling of old scores, scapegoating–but any is as good as none at all if you don’t need one. The cruelty of the diaspora experience is not necessarily about change, but about loss–of tradition, of customs, of language, of an enduring mental landscape that has been left behind. The cruelty of nostalgia resides in the persistence of memory, of families, of lives, of art, of songs, of celebrations. Diaspora is about a separation from what is comfortable, what is expected, happiness, joy, friends, births, weddings, deaths. As a group of people fan out to find new homes, they meet the challenge of finding all the rest of the world already occupied, and if they have been forced to leave one place, they will probably be less than welcome wherever they go. Those who suffer diaspora, forced to leave their homes again and again, will eventually become errant and drifting, unwilling to call anywhere home. Eventually, after being rejected enough, you have an entire group of people with nothing to lose, wandering the world in search of a home. All people want a place to call their home. This is a basic human desire, to have a family and a job and a roof over our heads and not have to move every few years. Diaspora breaks up families, history and tradition are forgotten, identity becomes variable, languages are both forgotten and learned, The dead are left behind, forgotten in unattended graves. Possessions, the relics of tradition, must be packed and transported or left behind. Wealth and land are left behind, lost forever. Perhaps new beginnings in new places can be a good thing as it has been for immigrants around the world, but the nostalgia for what has been lost is an ethos that has come to be emblematic of the human condition. In many ways, diaspora is the human condition.

Though I have lived far from home, spoken a language I had to learn, eaten strange food, missed my family, I have never been forced to leave my homeland never to return, yet for many people, it has happened more than once, and it continues to be the their “pan de cada día” or their everyday experience. Diaspora is about the scattering of a people, a forced exile, a leaving behind, a tragedy, a disaster. Diaspora has many causes–wars, revolutions, racial cleansing, religious unity, human cruelty, the settling of old scores, scapegoating–but any is as good as none at all if you don’t need one. The cruelty of the diaspora experience is not necessarily about change, but about loss–of tradition, of customs, of language, of an enduring mental landscape that has been left behind. The cruelty of nostalgia resides in the persistence of memory, of families, of lives, of art, of songs, of celebrations. Diaspora is about a separation from what is comfortable, what is expected, happiness, joy, friends, births, weddings, deaths. As a group of people fan out to find new homes, they meet the challenge of finding all the rest of the world already occupied, and if they have been forced to leave one place, they will probably be less than welcome wherever they go. Those who suffer diaspora, forced to leave their homes again and again, will eventually become errant and drifting, unwilling to call anywhere home. Eventually, after being rejected enough, you have an entire group of people with nothing to lose, wandering the world in search of a home. All people want a place to call their home. This is a basic human desire, to have a family and a job and a roof over our heads and not have to move every few years. Diaspora breaks up families, history and tradition are forgotten, identity becomes variable, languages are both forgotten and learned, The dead are left behind, forgotten in unattended graves. Possessions, the relics of tradition, must be packed and transported or left behind. Wealth and land are left behind, lost forever. Perhaps new beginnings in new places can be a good thing as it has been for immigrants around the world, but the nostalgia for what has been lost is an ethos that has come to be emblematic of the human condition. In many ways, diaspora is the human condition.

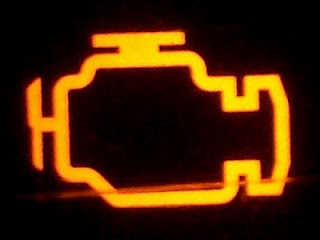

On the "check engine" light

So my “check engine” light came on last week. I hate the “check engine” light. I hate it because it doesn’t really tell you what’s wrong, just that something is wrong. It wasn’t blinking, which is worse because then the engine is telling you that you are in imminent danger of blowing the hell up if you don’t pull over and stop. This was just the steady amber that indicates that something is wrong. It nags you into taking the car into the shop because it is a mystery. That little yellow light tells you nothing, and is an enigma wrapped in a mystery enclosed in a conundrum. You, average driver and normal person, do not understand the mystery of the amber “check engine” light because you have not been inducted into the secret society of auto mechanics that check engines. On a few occasions I have noticed that if you don’t put the gas cap on correctly, this will act as if there were a leak in the fuel system and the “check engine” light will come on. I checked my gas cap, and it seemed to be acting funny, but the light did not go off. I went to the garage yesterday and they kept the vehicle for over five hours. Finally, they called and said, “You gas cap is broken and won’t seal properly.” But they didn’t have a new gas cap and had to overnight one from someplace. I went back to the garage and picked my car up–I had errands to run. All of this is very mysterious. Where was the new gas cap coming from? How could they get one “overnight”? They removed the “check engine” light. Today they called, “Come in at one and we’ll fix it.” So I did. Now my “check engine” light is off, my life is back to normal, and all is right with the world. Actually, none of that is true except that the “check engine” light is off. On all other accounts, my life is just as chaotic as ever. Does life have a “check engine” light? I know life has no gas cap, or anything that is even the least bit metaphorically a gas cap. Maybe I don’t even want to think about that. Here’s hoping that your “check engine” light does not come on, not now, not ever.