Human beings are intrigued by the unknown and strive endlessly to know more, to clear up the mystery. Yet, we are also plagued by the unknown, the inexplicable, the mysterious. Modern manifestations of pop culture delve deeply in the mystery genre, and weird pop culture delves into cryptozoology and make-believe monsters, trading in ancient astronauts and Bermuda Triangles. Many mysteries are not mysteries at all when seen against the background of real science and rational empiricism. A person disappears, a bank is robbed, someone lies dead in their own living room, a painting is stolen, the power goes out, a window get broken, the car won’t start, your stomach hurts, and you don’t have an explanation for any of it. A letter is lost in the mail, the washing machine breaks, the roof leaks. We have a hundred mysteries around us all of the time: a strange noise in the night, a familiar looking face at the mall that you haven’t seen in twenty years, a ringing phone but no one answers. We are constantly trying to solve one mystery or another. One of the greatest fictional detectives of all times, Sherlock Holmes, is the modern model and poster boy for mystery solving and rational empiricism. Holmes’ success drove his creator, Conan Doyle, to distraction because he had no idea his detective would turn into one of the wildly successful characters of all time. The mystery genre publishes thousands of new titles every year–the reading public can’t get enough. Mysteries are probably popular because the mirror the chaos of daily life, and since we can’t bring order to real life, we live vicariously through the detectives that bring order to their fictional world. We feel better about our own chaos as order is restored when the detective lets us know that the butler did it.

Category Archives: mystery

On mystery

Human beings are intrigued by the unknown and strive endlessly to know more, to clear up the mystery. Yet, we are also plagued by the unknown, the inexplicable, the mysterious. Modern manifestations of pop culture delve deeply in the mystery genre, and weird pop culture delves into cryptozoology and make-believe monsters, trading in ancient astronauts and Bermuda Triangles. Many mysteries are not mysteries at all when seen against the background of real science and rational empiricism. A person disappears, a bank is robbed, someone lies dead in their own living room, a painting is stolen, the power goes out, a window get broken, the car won’t start, your stomach hurts, and you don’t have an explanation for any of it. A letter is lost in the mail, the washing machine breaks, the roof leaks. We have a hundred mysteries around us all of the time: a strange noise in the night, a familiar looking face at the mall that you haven’t seen in twenty years, a ringing phone but no one answers. We are constantly trying to solve one mystery or another. One of the greatest fictional detectives of all times, Sherlock Holmes, is the modern model and poster boy for mystery solving and rational empiricism. Holmes’ success drove his creator, Conan Doyle, to distraction because he had no idea his detective would turn into one of the wildly successful characters of all time. The mystery genre publishes thousands of new titles every year–the reading public can’t get enough. Mysteries are probably popular because the mirror the chaos of daily life, and since we can’t bring order to real life, we live vicariously through the detectives that bring order to their fictional world. We feel better about our own chaos as order is restored when the detective lets us know that the butler did it.

On Van Helsing

Professor Van Helsing is a tribute to rational empiricism that has met the supernatural and had to back off because the experience did not square with reality. I like Van Helsing because he is so grounded in his science and empiricism that he is the true paradigm of rational thinking and practice. Yet, Van Helsing is faced with a situation that does not fit within the neat theories and hypothesis of his enlightened scientific experience. Through observation and experimentation, Van Helsing has cast his lot in life far from emotion, superstition, irrationality, and the supernatural. He writes books, carries out experiments, teaches his classes, is a paradigm of the enlightened scientist, the rock on which we build our reality. Yet, his situation, though a completely imaginary one, is problematic in the sense that he is faced with the larger problem of a reality–an undead, dead person–that cannot exist in his world. The philosophical implications of facing the existence of Dracula are vast and troubling. You are either a rational empiricist who cannot “believe” in such things, or you abandon your empiricism and throw in with the holy water, garlic, cross, and stake. Our empiricism protects us from foolish pseudo-science such as astrology, palmistry, quiromancy, numerology, tarot, Big Foot, the Loch Ness monster, werewolves, vampires, and necromancy, but is that all there is in this world? I have always sided with Hamlet: There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy. – Hamlet (1.5.167-8). Still, the philosophical problem persists even if only in our imaginations, hoping against hope that we never have to face this situation in the real world.

On Van Helsing

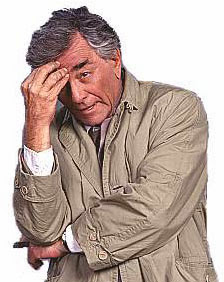

On Columbo

Like most people, I was always sucked in by Columbo. His sense of justice was fairly absolute, and he would stick to the killer until he had it figured out. The show was not a whodunnit, but it did show how Columbo would put the pieces of the puzzle together. The killers were always so mundane, killing for all of the most superficial of reasons–money, love, jealousy, fame–so predictable. His secret weapon is not that he feigns stupidity, but that he lets his personal humility run his investigations, letting his egotistical suspects hang themselves by lying when he asked them questions. He solved most of the crimes by simply letting his suspects talk. In Spain we say that it is easier to catch a liar than a one-legged man. Perhaps Columbo was successful because he was tenacious, hard-working, thoughtful, and creative–he had to be able to think like a murderer. I often wondered that if he were real, how would all of that violence and murders affect his personal life. He didn’t have time for big shots or people who thought they were better than others. He rejected the lives of the rich and famous while taking great pleasure in a simple bowl of chili. He loved his wife, took care of his dog, and drove an old Peugeot. He never dabbled in the materialistic world of his suspects, perhaps because he understood the trap of uncontrolled materialism so well. By not desiring more than he ever had and taking pleasure in life’s simple things, he had enough perspective to understand why people fail so miserably at life and kill others. That he smoked those miserable cigars and annoyed people with his incessant questions is irrelevant, part of the “smoke” screen that would put his prey at ease, allowing him to work out the complex solutions for which he was so well-known.

On Columbo

Like most people, I was always sucked in by Columbo. His sense of justice was fairly absolute, and he would stick to the killer until he had it figured out. The show was not a whodunnit, but it did show how Columbo would put the pieces of the puzzle together. The killers were always so mundane, killing for all of the most superficial of reasons–money, love, jealousy, fame–so predictable. His secret weapon is not that he feigns stupidity, but that he lets his personal humility run his investigations, letting his egotistical suspects hang themselves by lying when he asked them questions. He solved most of the crimes by simply letting his suspects talk. In Spain we say that it is easier to catch a liar than a one-legged man. Perhaps Columbo was successful because he was tenacious, hard-working, thoughtful, and creative–he had to be able to think like a murderer. I often wondered that if he were real, how would all of that violence and murders affect his personal life. He didn’t have time for big shots or people who thought they were better than others. He rejected the lives of the rich and famous while taking great pleasure in a simple bowl of chili. He loved his wife, took care of his dog, and drove an old Peugeot. He never dabbled in the materialistic world of his suspects, perhaps because he understood the trap of uncontrolled materialism so well. By not desiring more than he ever had and taking pleasure in life’s simple things, he had enough perspective to understand why people fail so miserably at life and kill others. That he smoked those miserable cigars and annoyed people with his incessant questions is irrelevant, part of the “smoke” screen that would put his prey at ease, allowing him to work out the complex solutions for which he was so well-known.

On walking in the snow

Walking in the snow is balm to the jagged nerves that the holidays tend to exacerbate. While it was snowing a couple of days ago, I went out for a walk to think about things. Into all lives a certain amount of chaos will always fall: people get older, they get sick and die, or they spend extended amounts of time in the process of dying. This isn’t morbid, it’s just real. The snow falls and reminds me that the seasons change, time goes by, we all get older, everything changes, nothing stays the same except the snow. Walking in the snow reminded me of all the other times in my life that I have walked in the snow–in Minnesota, in Spain, in Texas, in Nevada, in Canada. The snow is silent, gentle, and impersonal–it falls on the just and the unjust equally, and it always will. It covers the sleeping landscape, giving the earth a chance to sleep under an icy blanket, a white death shroud that lovingly envelops everything. When you walk in the snow, you become a part of the shroud, you are a part of death, the silence of the falling snow, the eternity of a single moment. A single snow flake is proof that the entire universe moves towards lowest energy, towards entropy, and we are only incidental players on a universal stage.

On walking in the snow

Walking in the snow is balm to the jagged nerves that the holidays tend to exacerbate. While it was snowing a couple of days ago, I went out for a walk to think about things. Into all lives a certain amount of chaos will always fall: people get older, they get sick and die, or they spend extended amounts of time in the process of dying. This isn’t morbid, it’s just real. The snow falls and reminds me that the seasons change, time goes by, we all get older, everything changes, nothing stays the same except the snow. Walking in the snow reminded me of all the other times in my life that I have walked in the snow–in Minnesota, in Spain, in Texas, in Nevada, in Canada. The snow is silent, gentle, and impersonal–it falls on the just and the unjust equally, and it always will. It covers the sleeping landscape, giving the earth a chance to sleep under an icy blanket, a white death shroud that lovingly envelops everything. When you walk in the snow, you become a part of the shroud, you are a part of death, the silence of the falling snow, the eternity of a single moment. A single snow flake is proof that the entire universe moves towards lowest energy, towards entropy, and we are only incidental players on a universal stage.

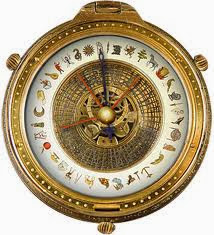

On "La muerte y la brújula" (by Borges)

“Death and the Compass” is a strange tale of problem-solving gone crazy and revenge. A weird riff on the stories of Sherlock Holmes, this is the detective story turned on its head. Both the detectives and the reader fall into the same preconceived concept that if a crime has been committed that the clues will point to a solution. What would happen if the the clues are false and create the illusion of a crime, but not the crime which is really being committed? What if the real crime behind the clues is invisible to everyone except the criminal? Except for the final paragraphs where the story goes off the rails, Borges’s strange detective tale starts out being a pretty standard whodunit taking place in urban Buenos Aires. Clues are strewn about the story as if they were going out of style. An old rabbi, who was working on some arcane Jewish mysticism, is murdered. It looks as though diamonds and sapphires might be involved, but everything is murky. The detective, Eric Lonnröt, is on the case, reading the rabbi’s research and tracking down clues. There are two more murders, and Lonnröt thinks he has the case solved, working his way through a labyrinth of strange clues, arcane literature, and geographic locations, using his compass to come up with the location of the fourth, and final, crime. He is hard on the heals of Red Sharlock, a criminal mastermind of organized crime in the city. Borges really knows how to suck in his readers, counting on reader expectations regarding the genre to put down a path of clues that can only lead to disaster. I could write out the solution, but then again, why let the cat out of the bag? The very story, the details, the clues, the characters all form a perfectly designed and orchestrated trap into which both the detective and the reader falls. The best part of all is that Borges gives the reader the solution from the very beginning. What neither detective nor reader understand is the difference between the real world and a simulacra of the world–Borges’s words, not mine. The solutions to most problems are usually the most simple ones which are linked in a direct line from problem to solution, and there is nothing either arcane or obscure about a true solution.

On "La muerte y la brújula" (by Borges)

“Death and the Compass” is a strange tale of problem-solving gone crazy and revenge. A weird riff on the stories of Sherlock Holmes, this is the detective story turned on its head. Both the detectives and the reader fall into the same preconceived concept that if a crime has been committed that the clues will point to a solution. What would happen if the the clues are false and create the illusion of a crime, but not the crime which is really being committed? What if the real crime behind the clues is invisible to everyone except the criminal? Except for the final paragraphs where the story goes off the rails, Borges’s strange detective tale starts out being a pretty standard whodunit taking place in urban Buenos Aires. Clues are strewn about the story as if they were going out of style. An old rabbi, who was working on some arcane Jewish mysticism, is murdered. It looks as though diamonds and sapphires might be involved, but everything is murky. The detective, Eric Lonnröt, is on the case, reading the rabbi’s research and tracking down clues. There are two more murders, and Lonnröt thinks he has the case solved, working his way through a labyrinth of strange clues, arcane literature, and geographic locations, using his compass to come up with the location of the fourth, and final, crime. He is hard on the heals of Red Sharlock, a criminal mastermind of organized crime in the city. Borges really knows how to suck in his readers, counting on reader expectations regarding the genre to put down a path of clues that can only lead to disaster. I could write out the solution, but then again, why let the cat out of the bag? The very story, the details, the clues, the characters all form a perfectly designed and orchestrated trap into which both the detective and the reader falls. The best part of all is that Borges gives the reader the solution from the very beginning. What neither detective nor reader understand is the difference between the real world and a simulacra of the world–Borges’s words, not mine. The solutions to most problems are usually the most simple ones which are linked in a direct line from problem to solution, and there is nothing either arcane or obscure about a true solution.