Very few of the books in my library were bought new. Most have a history of multiple owners, multiple readers, multiple histories. Is there anything sadder than a pristine copy of book that has never been opened? Digging through the stacks of a used book store does not always pay dividends, but it often offers up a surprise or two, something you never thought you’d find, or better yet, something you never knew existed. A used book carries its history written, literally, on its sleeve. A little tattered, perhaps, some accumulated marginalia, random underlining, dog-eared, yellowing, a used book has given up its information on more than one occasion. Used books are all different–sizes, heights, colors, widths–and form an odd collage of shapes, patterns, and textures, misfits, as it were. Used books from a variety of times and places populate a bookshelf in an original way that is unique to my collection. Perhaps there is something aesthetically appealing to having a set of books which are all bound in the same way, but it’s not as interesting as a haphazard grouping of used books acquired over a number of years in a variety of places. Used books have character, a back-story, history, an aroma which new books do not have. And used books don’t just come from used book stores. They come from other book collectors, garage sales, random antique stores, a stray vendor on a street corner. Obtaining used books is almost as interesting as having them. Building a library of your own books is satisfying and personal because you know that no one has what you have. Old books are about nostalgia, familiar stories, coming-of-age, epiphanies, research, writing, and meaning because books “mean” on a couple of levels: books are about knowledge, the accumulation of wisdom, commentary, communication. Books stand for the tradition of passing on knowledge, for the aesthetics of the word, for naming and signifying, infinitely as signs are passed from one generation of writers to another as they read their used books, make their marginal notes, form their new sentences, focus on the ideas that percolate up through the words that leak from their pens. Used books speak to an intentionality beyond the purposeful act of writing that will be the source and root for countless other writers and their new books. Old books, used books speak to reading and research, pleasure and discovery, contemplation and examination. Each book contains its own unique form and sign which also makes it like all of the other books, so the group melds and blends, juxtapositions of words, signs, and signified that create something new. So used books are much more than just books, but they were never just books in the first place. Their very presence is about our own curiosity about the world, ourselves, and the universe. Used books, new readings, old ideas, all meld in the imagination of the writer/reader/owner who is just trying to resolve the meaning of life without starting at the beginning again.

Category Archives: books

On used books

Very few of the books in my library were bought new. Most have a history of multiple owners, multiple readers, multiple histories. Is there anything sadder than a pristine copy of book that has never been opened? Digging through the stacks of a used book store does not always pay dividends, but it often offers up a surprise or two, something you never thought you’d find, or better yet, something you never knew existed. A used book carries its history written, literally, on its sleeve. A little tattered, perhaps, some accumulated marginalia, random underlining, dog-eared, yellowing, a used book has given up its information on more than one occasion. Used books are all different–sizes, heights, colors, widths–and form an odd collage of shapes, patterns, and textures, misfits, as it were. Used books from a variety of times and places populate a bookshelf in an original way that is unique to my collection. Perhaps there is something aesthetically appealing to having a set of books which are all bound in the same way, but it’s not as interesting as a haphazard grouping of used books acquired over a number of years in a variety of places. Used books have character, a back-story, history, an aroma which new books do not have. And used books don’t just come from used book stores. They come from other book collectors, garage sales, random antique stores, a stray vendor on a street corner. Obtaining used books is almost as interesting as having them. Building a library of your own books is satisfying and personal because you know that no one has what you have. Old books are about nostalgia, familiar stories, coming-of-age, epiphanies, research, writing, and meaning because books “mean” on a couple of levels: books are about knowledge, the accumulation of wisdom, commentary, communication. Books stand for the tradition of passing on knowledge, for the aesthetics of the word, for naming and signifying, infinitely as signs are passed from one generation of writers to another as they read their used books, make their marginal notes, form their new sentences, focus on the ideas that percolate up through the words that leak from their pens. Used books speak to an intentionality beyond the purposeful act of writing that will be the source and root for countless other writers and their new books. Old books, used books speak to reading and research, pleasure and discovery, contemplation and examination. Each book contains its own unique form and sign which also makes it like all of the other books, so the group melds and blends, juxtapositions of words, signs, and signified that create something new. So used books are much more than just books, but they were never just books in the first place. Their very presence is about our own curiosity about the world, ourselves, and the universe. Used books, new readings, old ideas, all meld in the imagination of the writer/reader/owner who is just trying to resolve the meaning of life without starting at the beginning again.

On the e-book

This is the age of the e-book, whether that be Nook or Kindle or some other format, the e-book is quickly making huge inroads in the book market. For the first time, major best sellers are now selling more digital versions than paper-print versions. Is this the end of the paper book? I love paper books and probably have between five and six thousand. Some of my favorite and most beloved titles are prominently displayed in my living room where all guests might see them. The traditional paper book platform is so different than the digital platform that all comparisons must be apples to oranges. The e-book is a kind of a ghost, disembodied, phantasmal, incorporeal, non-existent. Without the digital platform of electronics and electricity, it is dead, but if you want to travel to Europe for the summer, and you want to take three hundred books, your only real option is a tablet with e-reader software. Yet, no one has a relationship with their tablet. It is impersonal, identical to all other tablets, cold, digital, icy. So in some respects the tablet with e-reader software is a practical investment for reading in situations where you can’t be near your library–I get that and have a tablet with the appropriate software, and I use it. Nevertheless, there is something about a book, a real book, a paper book with printing and ink and covers. They weigh something, they are solid, you can hold it in your hand, it will take up space in your bag, it will have a history, and it will be unique. Did someone scrawl a dedication in it when they gave it to you for some special occasion? Was it already used and old when it came into your possession? Did you find it abandoned in on a chair in an airport or did you buy it from a random street vendor on a corner in Madrid? Is it part of a special collection that you are rounding up? Books are tactile and create a visual space, which occupies in the mind’s eye of the reader. All different sizes, all different colors, some thick, some thin, some books you can use to prop open a door. They are relics, some sacred, some less so, but relics nonetheless. Each book represents a story, a human story of loss, of shame, of triumph, or heroism, or cowardice, of sacrifice, of wisdom, or justice. Whether it is a slim volume of love poetry that breaks your heart, or a thick tome on human tragedy that drags you through the cathartic agony of failure and redemption, books will move you to think and feel, and as you think and feel you will imbue a volume with your memories and emotions, and every time you see that book, you will remember your reading experience that was unique and will always be linked in your heart to a particular volume. I am not trying to invoke some ideal time in the past when book culture was ideal, nor I am suffering from romantic nostalgia founded on nothing more than an irrational yearning for some golden moment in my own history. Books are handy, uncomplicated, physical, analogue, simple, unambiguous, solid, sturdy, and helpful. Perhaps a happy co-existence of platforms is what we really need.

On the e-book

This is the age of the e-book, whether that be Nook or Kindle or some other format, the e-book is quickly making huge inroads in the book market. For the first time, major best sellers are now selling more digital versions than paper-print versions. Is this the end of the paper book? I love paper books and probably have between five and six thousand. Some of my favorite and most beloved titles are prominently displayed in my living room where all guests might see them. The traditional paper book platform is so different than the digital platform that all comparisons must be apples to oranges. The e-book is a kind of a ghost, disembodied, phantasmal, incorporeal, non-existent. Without the digital platform of electronics and electricity, it is dead, but if you want to travel to Europe for the summer, and you want to take three hundred books, your only real option is a tablet with e-reader software. Yet, no one has a relationship with their tablet. It is impersonal, identical to all other tablets, cold, digital, icy. So in some respects the tablet with e-reader software is a practical investment for reading in situations where you can’t be near your library–I get that and have a tablet with the appropriate software, and I use it. Nevertheless, there is something about a book, a real book, a paper book with printing and ink and covers. They weigh something, they are solid, you can hold it in your hand, it will take up space in your bag, it will have a history, and it will be unique. Did someone scrawl a dedication in it when they gave it to you for some special occasion? Was it already used and old when it came into your possession? Did you find it abandoned in on a chair in an airport or did you buy it from a random street vendor on a corner in Madrid? Is it part of a special collection that you are rounding up? Books are tactile and create a visual space, which occupies in the mind’s eye of the reader. All different sizes, all different colors, some thick, some thin, some books you can use to prop open a door. They are relics, some sacred, some less so, but relics nonetheless. Each book represents a story, a human story of loss, of shame, of triumph, or heroism, or cowardice, of sacrifice, of wisdom, or justice. Whether it is a slim volume of love poetry that breaks your heart, or a thick tome on human tragedy that drags you through the cathartic agony of failure and redemption, books will move you to think and feel, and as you think and feel you will imbue a volume with your memories and emotions, and every time you see that book, you will remember your reading experience that was unique and will always be linked in your heart to a particular volume. I am not trying to invoke some ideal time in the past when book culture was ideal, nor I am suffering from romantic nostalgia founded on nothing more than an irrational yearning for some golden moment in my own history. Books are handy, uncomplicated, physical, analogue, simple, unambiguous, solid, sturdy, and helpful. Perhaps a happy co-existence of platforms is what we really need.

On the Necronomicon

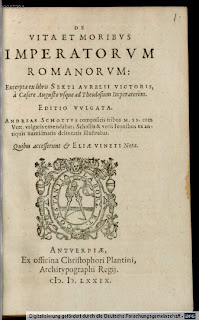

As a lover of fine wines, old manuscripts, and castles, I will often stop at the odd street bookseller to see what they might have to offer, and I have often found strange and wonderful things that I would never have had a chance to acquire otherwise. While perusing the stash of a one-legged man in Madrid’s Rastro one sunny day January of 1984, I came across an old leathery volume which look both abandoned and abused. I was a little hung-over and very crabby, having slept on my own couch after a rather heated argument with another person. So I had escaped to the Rastro, looking for coffee and distraction. The poor little volume in octavo was bound in a deep purple calfskin, but the binding was broken, the corners were worn and bent, and a page was hanging out, loose. The imprint on the title page was 1598, published in Seville by Saenz Lope de Heredia e hijos. I paid the man 300 pesetas, and he was glad to it. I tucked the book into my backpack and moved on. Given the nature of my personal circumstances, the book eventually went missing for almost twenty years. In the vernacular, I recalled, wrongly, that the title was Necronomicon or de rerum necromancibus or Necronecronicom or maybe not that all, but I was sure that it was a second or third impression of a book that was originally published in Munich in 1575, warning against the practice of necromancy. I didn’t care so much for it’s contents, but I knew the book was rare and that no extant complete copies existed in any libraries public or private. Most collectors thought it to be a myth–that it never really existed at all. When I opened the mailbox yesterday, there was one package with a postmark from Buenos Aires. She had gone to Buenos Aires and taken my purple book. The author, as I imperfectly remember, was a certain Andreas Valerius Schottus de Zaragoza, who after fleeing the Inquisition in Valencia was also known for Origo gentis romanae, (1579) a manuscript from Theodore Poelmann, printed with De Vita et Mortis Imperatorum Romanorum. I knew about Schottus, but I never seen this particular book attributed to him. Some collectors have speculated that Schottus never existed either and that this was a pseudonym for the archbishop of Toledo, Bartolomé Carranza (1558-1576). Since the book dealt with prohibited, even heretical ideas, there were no official seals or approvals from the Inquisition, meaning that all the publication material on the title page was false, including the identity of the author and the date and city of publication. I did nothing with the book, now even more battered than when I bought it in Madrid twenty-seven years ago, and it lingered untouched on a shelf until a few weeks ago when it vanished. I think I lent it by accident to a colleague that was looking for an original copy of Luzan’s, La Poetica, 6 Reglas de la poesia en general y de sus principales especies (1737), which as you may guess was bound in purple calfskin. My colleague’s suitcase was subsequently lost on a flight to Heathrow Airport, and though he filed a claim on the bag, it and its contents were lost, probably auctioned off as lost and unclaimed luggage in a large storage building in suburban London. Since I don’t have the book, I cannot rightly claim that it ever existed, indeed, I have come to question any and all of my story, including details about the one-legged man. I thought at one point I had found a reference to Schottus and his Necronomicon in a story by H.P Lovecraft, but that proved to be erroneous as well. Most of this is true, in fact, except for a couple of names, some of the dates, and most of the facts concerning the acquisition and loss of a certain purple calfskin book.

On the Necronomicon

As a lover of fine wines, old manuscripts, and castles, I will often stop at the odd street bookseller to see what they might have to offer, and I have often found strange and wonderful things that I would never have had a chance to acquire otherwise. While perusing the stash of a one-legged man in Madrid’s Rastro one sunny day January of 1984, I came across an old leathery volume which look both abandoned and abused. I was a little hung-over and very crabby, having slept on my own couch after a rather heated argument with another person. So I had escaped to the Rastro, looking for coffee and distraction. The poor little volume in octavo was bound in a deep purple calfskin, but the binding was broken, the corners were worn and bent, and a page was hanging out, loose. The imprint on the title page was 1598, published in Seville by Saenz Lope de Heredia e hijos. I paid the man 300 pesetas, and he was glad to it. I tucked the book into my backpack and moved on. Given the nature of my personal circumstances, the book eventually went missing for almost twenty years. In the vernacular, I recalled, wrongly, that the title was Necronomicon or de rerum necromancibus or Necronecronicom or maybe not that all, but I was sure that it was a second or third impression of a book that was originally published in Munich in 1575, warning against the practice of necromancy. I didn’t care so much for it’s contents, but I knew the book was rare and that no extant complete copies existed in any libraries public or private. Most collectors thought it to be a myth–that it never really existed at all. When I opened the mailbox yesterday, there was one package with a postmark from Buenos Aires. She had gone to Buenos Aires and taken my purple book. The author, as I imperfectly remember, was a certain Andreas Valerius Schottus de Zaragoza, who after fleeing the Inquisition in Valencia was also known for Origo gentis romanae, (1579) a manuscript from Theodore Poelmann, printed with De Vita et Mortis Imperatorum Romanorum. I knew about Schottus, but I never seen this particular book attributed to him. Some collectors have speculated that Schottus never existed either and that this was a pseudonym for the archbishop of Toledo, Bartolomé Carranza (1558-1576). Since the book dealt with prohibited, even heretical ideas, there were no official seals or approvals from the Inquisition, meaning that all the publication material on the title page was false, including the identity of the author and the date and city of publication. I did nothing with the book, now even more battered than when I bought it in Madrid twenty-seven years ago, and it lingered untouched on a shelf until a few weeks ago when it vanished. I think I lent it by accident to a colleague that was looking for an original copy of Luzan’s, La Poetica, 6 Reglas de la poesia en general y de sus principales especies (1737), which as you may guess was bound in purple calfskin. My colleague’s suitcase was subsequently lost on a flight to Heathrow Airport, and though he filed a claim on the bag, it and its contents were lost, probably auctioned off as lost and unclaimed luggage in a large storage building in suburban London. Since I don’t have the book, I cannot rightly claim that it ever existed, indeed, I have come to question any and all of my story, including details about the one-legged man. I thought at one point I had found a reference to Schottus and his Necronomicon in a story by H.P Lovecraft, but that proved to be erroneous as well. Most of this is true, in fact, except for a couple of names, some of the dates, and most of the facts concerning the acquisition and loss of a certain purple calfskin book.

On paper books

Today marks the publication of the non-Potter book by author J. K. Rowling, and millions of copies have been sold, the majority being digital versions with paper copies coming in a distant second. The paradigm of the format of the best-seller has changed. Paper is no longer king, and digital e-readers of various kinds have taken the capitalist high ground. Book stores have fewer customers every day, and the paper book industry is dying. This is a shame because although e-readers are easy to carry around, there is some doubt as to the ownership of the digital versions once the owner passes on. In other words, when you die, your library goes with you. You can buy a digital book for another person, but you can’t give them your copy to read. The paper book is such a beautiful invention that it seems a real shame that in ten years no one will be making or selling them anymore. Or will they? Paper books are a basic technology which works even when the batteries in your e-reader or tablet have gone flat. You can read a paper book on take-off and landing without provoking the disapproval and ire of the flight crew. There is something comfortable about flipping through the pages. Perhaps I’m am only nostalgic for a golden age of publishing in which the latest popular titles were stacked in big piles in the bookstores, and bookstores were my candy stores filled with mysteries, science fiction, biographies, histories, novels, and names such as Christie, Heinlein, Heller, Salinger, Bradbury, and Conan Doyle were everywhere. Their books populate the shelves of my house, and any given moment, I can pull one down and start reading. Nevertheless, I had over seventy books on my e-reader this summer as I traveled to Europe and only one beat-up old paperback on shipwreck in my carry-on. Just in case. Paper books are bulky and hard to move. Old books smell a little, but not always in a good way. Yet, I can take out a pencil and underline or add marginalia to my book, and I know you can do something similar with e-books, but it’s just not the same. Your comments in your handwriting six, seven or ten years later can tell you a lot about who you were the last time you read that book. There are books, older titles, that I can get for free and read on my tablet, and maybe I don’t want a paper copy, but I treasure my hardcopy of Catch-22, Watership Down, Ghost Story, Cry Me a River, The Stand, El nombre de la rosa, Going After Cacciato. Am I being irrational about my attachment to these silent sentries who guard the shelves of my house? They don’t feel anything. They are inanimate objects, lifeless, blind. The monster that is the e-book has me torn two ways: one, very convenient, clean, light; two, without batteries you have no book at all, you can’t lend it, it dissolves into nothing as you turn to dust. I have a sneaking suspicion that paper books, real books, will be around for much longer than we suspect, or is this just wishful thinking?

On paper books

Today marks the publication of the non-Potter book by author J. K. Rowling, and millions of copies have been sold, the majority being digital versions with paper copies coming in a distant second. The paradigm of the format of the best-seller has changed. Paper is no longer king, and digital e-readers of various kinds have taken the capitalist high ground. Book stores have fewer customers every day, and the paper book industry is dying. This is a shame because although e-readers are easy to carry around, there is some doubt as to the ownership of the digital versions once the owner passes on. In other words, when you die, your library goes with you. You can buy a digital book for another person, but you can’t give them your copy to read. The paper book is such a beautiful invention that it seems a real shame that in ten years no one will be making or selling them anymore. Or will they? Paper books are a basic technology which works even when the batteries in your e-reader or tablet have gone flat. You can read a paper book on take-off and landing without provoking the disapproval and ire of the flight crew. There is something comfortable about flipping through the pages. Perhaps I’m am only nostalgic for a golden age of publishing in which the latest popular titles were stacked in big piles in the bookstores, and bookstores were my candy stores filled with mysteries, science fiction, biographies, histories, novels, and names such as Christie, Heinlein, Heller, Salinger, Bradbury, and Conan Doyle were everywhere. Their books populate the shelves of my house, and any given moment, I can pull one down and start reading. Nevertheless, I had over seventy books on my e-reader this summer as I traveled to Europe and only one beat-up old paperback on shipwreck in my carry-on. Just in case. Paper books are bulky and hard to move. Old books smell a little, but not always in a good way. Yet, I can take out a pencil and underline or add marginalia to my book, and I know you can do something similar with e-books, but it’s just not the same. Your comments in your handwriting six, seven or ten years later can tell you a lot about who you were the last time you read that book. There are books, older titles, that I can get for free and read on my tablet, and maybe I don’t want a paper copy, but I treasure my hardcopy of Catch-22, Watership Down, Ghost Story, Cry Me a River, The Stand, El nombre de la rosa, Going After Cacciato. Am I being irrational about my attachment to these silent sentries who guard the shelves of my house? They don’t feel anything. They are inanimate objects, lifeless, blind. The monster that is the e-book has me torn two ways: one, very convenient, clean, light; two, without batteries you have no book at all, you can’t lend it, it dissolves into nothing as you turn to dust. I have a sneaking suspicion that paper books, real books, will be around for much longer than we suspect, or is this just wishful thinking?

On libraries

Libraries, collections of books, magazines, and newspapers, have always given me a home away from home. I keep my own library both in my office and at home. Having books has always been important to me, but mega-collections of volumes offer a silent monument to imagination, creativity, research, personal effort, and perseverance. Somebody cared enough to write those books, to share their vision of their field, to offer up to humanity their grain of knowledge, to struggle to publish their work, making it, more or less, permanent. Even as a small child, once I figured out what books and libraries did, I was hooked, spending hours reading all kinds of works–novels, short stories, true life adventures, history, biography, science, philosophy, and poetry. I couldn’t buy all the books I wanted, and even if I could, where would I put them all? Above all, though, libraries are about sharing the books, communing with others in the study carrels and stacks. The quiet of libraries has often been a peaceful island where I could write papers, read long novels, study the plays of William Shakespeare, compose poetry, nap, contemplate the world, explore the existential angst implicit in the very fact of a huge library. There is nothing quite like finding a book of which you have only heard, but never seen, to take it off of the shelf and begin paging through it. Perhaps it is the orderliness of libraries with their complex numbering systems that break books into categories, subjects, genres, themes, epochs, and authors. The orderliness is comforting and predictable, and if you know one library, you can navigate almost any library with a similar system. Checking out books is, of course, an enormous privilege that most libraries in the USA allow, a reality which is not as readily available elsewhere. So you sit with your books at your study carrel in the library, half of them are open to important pages as you take notes, write a thesis paragraph, scratch your head. Time stops while you are in the library, and even though you think it’s 2012, it’s really 1955, or even 1845. Libraries are a liminal space out of time and out of space, a repository for knowledge and art, a place where librarians process books, people read, write, create, sleep, dream. The stacks are a labyrinth, consisting of books, people, librarians, chairs, desks, staircases, windows, offices. Yet I wonder for how much longer. The digital age is making serious inroads in the physical diffusion of books, and just this year more digital books that paper books were sold. I fear that my oasis of learning and intellectual pursuit may soon fit into a tablet, and that the libraries will close because no one will need them anymore. If you can get every book in the library without ever leaving your house, why go in the first place?

On libraries

Libraries, collections of books, magazines, and newspapers, have always given me a home away from home. I keep my own library both in my office and at home. Having books has always been important to me, but mega-collections of volumes offer a silent monument to imagination, creativity, research, personal effort, and perseverance. Somebody cared enough to write those books, to share their vision of their field, to offer up to humanity their grain of knowledge, to struggle to publish their work, making it, more or less, permanent. Even as a small child, once I figured out what books and libraries did, I was hooked, spending hours reading all kinds of works–novels, short stories, true life adventures, history, biography, science, philosophy, and poetry. I couldn’t buy all the books I wanted, and even if I could, where would I put them all? Above all, though, libraries are about sharing the books, communing with others in the study carrels and stacks. The quiet of libraries has often been a peaceful island where I could write papers, read long novels, study the plays of William Shakespeare, compose poetry, nap, contemplate the world, explore the existential angst implicit in the very fact of a huge library. There is nothing quite like finding a book of which you have only heard, but never seen, to take it off of the shelf and begin paging through it. Perhaps it is the orderliness of libraries with their complex numbering systems that break books into categories, subjects, genres, themes, epochs, and authors. The orderliness is comforting and predictable, and if you know one library, you can navigate almost any library with a similar system. Checking out books is, of course, an enormous privilege that most libraries in the USA allow, a reality which is not as readily available elsewhere. So you sit with your books at your study carrel in the library, half of them are open to important pages as you take notes, write a thesis paragraph, scratch your head. Time stops while you are in the library, and even though you think it’s 2012, it’s really 1955, or even 1845. Libraries are a liminal space out of time and out of space, a repository for knowledge and art, a place where librarians process books, people read, write, create, sleep, dream. The stacks are a labyrinth, consisting of books, people, librarians, chairs, desks, staircases, windows, offices. Yet I wonder for how much longer. The digital age is making serious inroads in the physical diffusion of books, and just this year more digital books that paper books were sold. I fear that my oasis of learning and intellectual pursuit may soon fit into a tablet, and that the libraries will close because no one will need them anymore. If you can get every book in the library without ever leaving your house, why go in the first place?