Gender Relations

Audio from Gitz Rice’s 1918 song, Dear Old Pal of Mine

Wartime is an excellent platform to explore differences in gender relations and expectations. The music of the Spencer Collection vividly shows us some of the prevalent themes that were widely accepted in the early 19th Century: men had to fight for their women and women had to wait for their men. Songs such as Knit, knit, knit, and I’m gonna pin a medal on the girl I left behind show that men fulfilled the role of the soldier while women were expected to fill the role of the weeping woman who patiently longed for their husband/son to return home.

Irving Berlin composed this song in 1918 and it is an excellent guide to how men and women were supposed to act. The man in the song wins a medal but explains to his friends that he’s going to pin it to his girlfriend back home because, “She deserves it more than I.” The aforementioned girl earned this right because when she said goodbye to him she held back her tears and hasn’t complain in the letters she sent him. This, the song is arguing, is the perfect relationship: the man does his duty and the woman doesn’t complain and faithfully waits for him to return.

The themes in Mammy’s Dixie Soldier Boy are very similar with the first song. Composed by Norman Landman in 1918, the song reiterates what makes a good woman in wartime. However, unlike the previous song, this one has the mother breaking down into tears after doing her best to be stoic and understanding of her son’s military service.

Another song composed by Irving Berlin in 1918, this one allows us to glimpse at what a young soldier is dreaming about while fighting overseas in Europe. It is a touching piece, and does much to humanize a young man who is fighting in a terrible conflict. Chief among the topics of his dreams is, “the girl [he] left behind.” In this regard, we can see that the song is arguing that males use the thought of the women they love as a coping mechanism, especially in times of war.

Gitz Rice follows this trend with his song Dear Old Pal of Mine, written in 1918. Opening with the line, “All my life is empty, since I went away,” the protagonist mournfully yearns for his beloved’s smile and “tender loving way.”

The last song of this segment was composed by Ivan Caryll in 1917. Women’s contributions to the war effort in World War One are often unnoticed, and this song is an excellent example of the little things that they would do to help. Although the majority of women worked in munitions factories and as nurses, the production of textiles was instrumental to the war effort. 1

Click here for an excerpt from Joshua S. Goldstein’s book, War and Gender.

Return to the homepage here.

- “Women’s Contribution in WW1,” Schoolworkhelper, http://schoolworkhelper.net/woman%E2%80%99s-contribution-in-ww1/. ↩

Racial Dilemna

African-American soldiers in the Spanish American War, 1898. Photo courtesy of LEARN NC, all rights reserved.

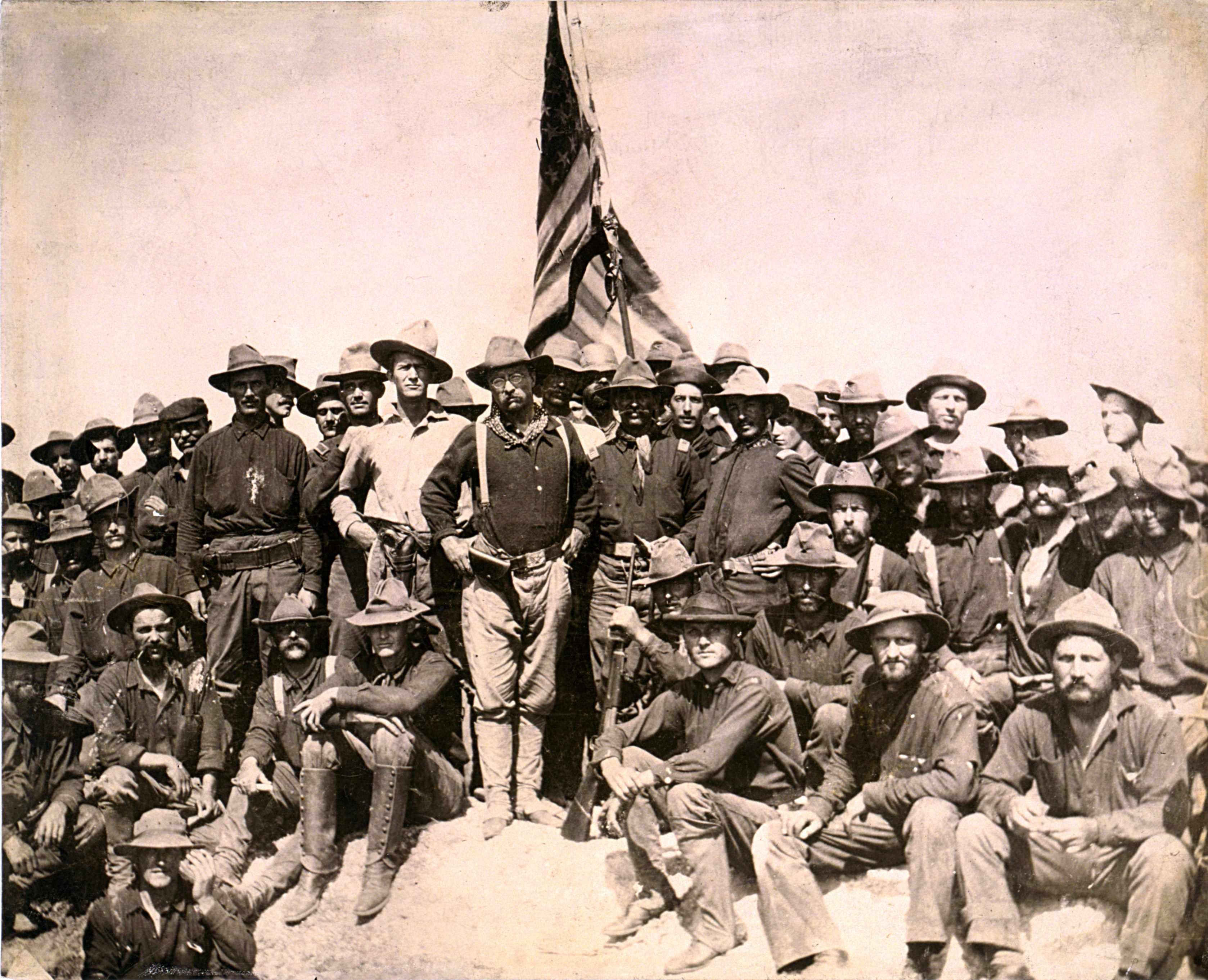

Perhaps the most interesting topic that is covered in the Spencer Collection is how race is discussed in wartime. Whenever a country has deep roots of prejudice about one race it takes hundreds of years and several progressive generations of citizens to allow acceptance. Another way to expedite this process is through the shared experience of combat. One impact of allowing African American soldiers into the army in the Civil War was a greater sense of self worth among those that served. They had fought and died beside their white brethren, and their courage and poise under fire could no longer be questioned. For a short time after the Civil War ended, the Reconstruction era went well for African Americans. Unfortunately, politics and racism derailed most of this progress so when the Spanish American War and First World War arrived, race relations had not changed much since the Civil War.

What makes the music fascinating during this time is that roughly half of the songs are in favor of letting African American soldiers fight for their country while the other half mock the supposed ineptitude and laziness of these same soldiers. This insight reveals a country that was still deeply divided over race, a topic that this country is still addressing to this day.

This song, composed by Harry DeCosta in 1918, is strongly in favor of allowing African American soldiers to fight for their country. A common theme in early African American culture was to reference how God would not judge a person based on their skin and the title of this song appeals to that sentiment.

Also noteworthy is the first line of the chorus which claims that, “Your Granddad did his duty in the Civil War he fell by his master’s side.” While songs such as this were progressive for their time, many would still have offhand remarks about the social stratification that was prevalent in the United States. African American soldiers who fought for the North in the Civil War were all free men and certainly did not have a master. While there is some evidence to support the fact that blacks fought for the Confederacy, their numbers were vastly smaller and rarely served as “official” soldiers.

Offensive cover art aside, this song composed by Harry Carroll in 1918 is another example of the songwriter happy with the idea of African American soldiers fighting for freedom and the opportunity to, “Give the whole world liberty, just like Lincoln did for me.”

It is ironic the song claims that Dixie will be proud of their old black Joe, especially because the protagonist claims to have fought in the Civil War for the North in 1861 and gained his freedom from people that wanted him enslaved.

You’ll Find Old Dixieland in France was composed by George Meyer in 1918 and is a perfect example of a song being simultaneously sympathetic and racist towards African Americans. It is perhaps best encapsulated in the line, “Instead of pickin’ melons off the vine, they’re picking Germans off the Rhine.”

This duality expressed by white American citizens (being happy that African Americans are fighting for their country while also perpetuating harmful stereotypes of these same soldiers) is indicative of the struggles faced by African Americans for hundreds of years.

Jigadeer Johnson was composed by Seneca Lewis in 1918. Described as a “comic” song, it relies heavily on racist phrases and stereotypes such as the myth of the lazy “Sambo” character. These characters were heavily used in minstrel shows and some of these stereotypes can, regrettably, be seen in modern culture as well.

Henry Murtagh composed this song in 1918. Private “Stonewall Jackson Lee,” an obvious reference to the two most well-known Confederate Generals of the Civil War, is accused of falling asleep on duty, another allusion to the lazy Sambo stereotype. The song continues its parade of ignorance by claiming the soldier was thinking of all the Christmas gifts he would be receiving, such as a trombone and watermelon.

Songs such as these reveal the contradictory relationship between African Americans and their fellow countrymen. Most of the songs agreed that these soldiers were just as brave as their white companions, especially in battle, but all too often they claim that these men are the exception to the rule.

Return to the homepage here.

- Robert L. Douglas, “Myth or Truth: A White and Black View of Slavery,” Journal of Black Studies vol. 19 (1989): 348. ↩

Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, 1898

Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, 1898